by Peter Tonguette

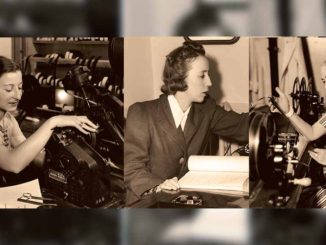

When Robert Benton’s Places in the Heart premiered in September 1984, the response was enthusiastic. Audiences turned out. Critics raved. In The New York Times, Vincent Canby invoked the names of European masters Buñuel, Renoir and Truffaut in describing the film’s artistry and impact. The following spring, the film was up for Academy Awards in seven categories, and when the Oscars were announced, two statuettes were handed out — one to Benton, for his screenplay, and another to leading actress Sally Field.

But the opinion that mattered most to the film’s editor, Carol Littleton, ACE, was that of Mildred Littleton, her mother, who had experienced the Great Depression depicted in Places in the Heart, and spent that part of her life in an area — Shawnee, Oklahoma — not far from the film’s Texas setting. As the film was being completed, she visited her daughter in Los Angeles for several weeks. One day, Carol took Mildred to the MGM Lab, where final work on the film was being done. As Carol, Benton and cinematographer Néstor Almendros, ASC, consulted with the color timer, Mildred watched the answer print. “Néstor was very sweet to her and very cavalier,” Littleton recalls. “Afterwards, I could see that Mother was quietly crying at the end, which was very unusual for a stoic Oklahoman.”

Places in the Heart weaves together the stories of several denizens of Waxahachie, Texas, who band together in 1935. There is Edna (Field), a widow compelled to come up with the funds to pay for her farm’s crushing mortgage. There is Moze (Danny Glover), an African-American farmhand whose offer of assistance gives Edna the idea to grow enough cotton to retain her farm, but who is subjected to brutal displays of racism from others in the town. And there is Mr. Will (John Malkovich), a taciturn sliver of a man, who returned from World War I missing his sight — and some of his humanity — and who becomes Edna’s reluctant boarder.

Mildred vouched for the authenticity of the film. “Carol, I know all these people,” she told her daughter. “This is the life I observed in the Depression. Many times people would come to my back door and ask for something to eat and I would give it to them” — referring to a moment in the opening credits montage. This was a film that actually earned that old cliché: It touched people’s hearts.

It touched Carol’s heart, too; because the film’s characters and events were recognizable to her family, so they were to her. “It’s the most personal film I’ve edited by far,” she says. The youngest of three daughters, Littleton was born in Oklahoma City, lived for much of her childhood in a small town called Miami and, at 12, moved to the country when her businessman father took up farming.

By the time she was offered Places in the Heart, Littleton had worked her way up from entry-level jobs to editor. She had spent time as a non-union editor of commercials and low- budget features before joining the Editors Guild in 1976. One of her first mainstream successes was Body Heat (1981), written and directed by Lawrence Kasdan, who recommended Littleton to Robert Benton. Benton — whose hometown is Waxahachie — told the Associated Press in 1984 that his screenplay was “a heavily fictionalized version of a number of stories that actually happened” in the lives of his family members.

When Littleton read it, she, too, found much with which to identify. “I just felt if there’s ever a film that I have to do, it’s this one,” she says. She had just finished E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), but the film had not come out — nor, of course, had her Oscar nomination for cutting it.

One of Benton’s requests for Littleton was that she join the company on location in Waxahachie. For the duration of the shoot, everyone stayed at a former Best Western hotel,” she says. Dailies were attended by cast and crew alike, “so we had a community feeling from day one.”

She developed friendships with many in the crew and several of the actors, including Glover, with whom she has since worked on Silverado (1985) and Grand Canyon (1991).

Other aspects of making the film in Waxahachie were more sobering. Places in the Heart depicts a town gripped by racism; shortly after the film begins, Edna’s husband is inadvertently shot and killed by a young black man, who is then made the victim of a lynching. Later, Edna is looked upon with derision for employing Moze, despite the fact that he alone stepped forward to help her.

As Littleton saw it, the legacy of racism was still in evidence. “Being on location and in the countryside, and seeing the racial divide in 1983 — as opposed to 1935 — things were not that different,” she laments. There were also reminders of the haves and have-nots of the film. “Cotton was no longer king in the economic picture of Texas, but oil was,” she adds. “And there was great wealth centered around oil, as there was around cotton.”

Places in the Heart does not inch from unpleasant realities of the day — not only racism, but sexism, evident in the faintly disdainful manner of the bank manager (Lane Smith) as he listens to Edna’s plans to shore up her nances. And there are natural disasters, too, as when Waxahachie is hit by a tornado. “I went through at least three tornadoes when I was a kid,” Littleton remembers. “I know the dread of coming out of the cellar and wondering if your house is still there.”

Her firsthand experience informed Benton’s decision to eschew planned visual effects, including what Littleton says was a “pitiful” foam- like tornado. She told him, “Benton, you know, it’s better to play the whole storm off -camera, on their faces.” Instead of models or animation, the film gives us the howl of the wind — Littleton praises the work of sound re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman, CAS as “one of the most beautiful mixing jobs of any film I’ve worked on” — and a succession of faces with eyes full of fear.

During editing, Benton looked to Littleton to interpret what he shot. He stood back from the process, preferring to view scenes projected on a big screen rather than on the KEM. Benton’s notes were general, she says. “He had an insightful way of being able to look at the material on the screen, and immediately afterwards say, ‘You know, we need more of a flow here’ or ‘Why don’t we examine this piece of music?’” Littleton relates. Benton’s biggest single point was for the storytelling to be simple. “The difficulty was being able to keep the film honest at all times — that we’re not seeing the hand of the filmmaker at all, as if it were unfolding like a picture book,” she continues.

In spite of its subject matter and storyline, Places in the Heart is never a downer. “It’s an affirmation of decent people trying to have a life of meaning and to prevail, to somehow prosper, to live ethically, to survive,” Littleton says. The opening credits montage is illustrative of the film’s tone. A choral rendition of the hymn “Blessed Assurance” is heard as we see a series of shots in Waxahachie. The images of family stability and material comfort (such as a family praying

before their dinner) are deeply appealing, while the images of strife and challenge (such as a woman who is living out of her car) nonetheless communicate hope for a better tomorrow. Shots captured by the second unit — of bluebells in bloom, a telephone pole-lined road, a lonely windmill — were intercut by Littleton. “Benton had primarily seen the credit sequence as vignettes, a visual introduction of the characters,” she says, “and I thought it needed to be interspersed with the town itself, giving it more scope from the beginning.” Throughout the rest of the film, she cuts to wide angles of two of Waxahachie’s most important institutions: the courthouse and the church. “The dominant image, the one that we go back to all the time, is the county courthouse,” she explains. “It almost looks like a cathedral. It’s the symbol of justice, of authority and of order in the world. And then we cut back to the church — the religious, ethical order in their lives.”

One of the trickiest scenes to edit also highlights the film’s basic theme — as Atticus Finch put it in another great work with a Depression-era setting, To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view.” After Will has moved into Edna’s house, he heedlessly enters the kitchen to complain about her children — not realizing that Edna is taking a bath. “She has kind of questioned all along whether he’s really blind, and he intrudes on her bath and then she realizes that he is in fact blind,” Littleton says. For Will, the moment is also one of discovery; he confirms, by his hand accidentally splashing the top of the

water in the tub, that in his ranting and raving, he has invaded Edna’s privacy. “It was a scene

that took a certain amount of skill to have both people in a parallel track of realizing a truth about each other,” Littleton says. “That’s the moment when Malkovich, as Mr. Will, starts to evolve.”

Many other scenes play in master shots. “We had conventional coverage,” Littleton says. “But I just felt, if it was unfolding in a take and it was holding, why cut away?” The most obvious example of not cutting away comes in the film’s celebrated ending. Communion is being given at the church, and the camera gently moves with the plate of tiny cups of wine as it passes from one churchgoer in the pew to the next, until we realize that all of the film’s characters are in attendance, including those no longer in town (such as Moze, who had to move following threats from the Ku Klux Klan) and those no longer among the living (such as Edna’s late husband and the young man who took his life, who sit together as if they were at peace with each other). “I think what surprised me most when I saw the last shot was the emotional power of an image to evoke the brotherhood of man,” Littleton says. But the shot almost didn’t happen.

The editor was called to the location when the crew was rehearsing the shot at Bethany Baptist Church. Benton said he was having trouble with the staging and felt he needed a new ending. Littleton asked him, “What are you talking about? You’re getting cold feet today?” There were problems with the camera rig snaking through the pews, which had to be removed a row at a time as the shot was unfolding, and concern that the take would be too noisy. But Littleton — along with producers Arlene Donovan and Michael Hausman, as well as Almendros — urged Benton to go through with the shot. Littleton told him, “Benton, this is the reason you’re making the movie.” Following several rehearsals and six takes, they got the shot. “It is the signature, transcendent ending of the film,” she says.

The success of Places in the Heart surprised Littleton. “Everybody thought, ‘Well, this is just a little movie,’” she says. She watched the film again recently, for the first time in about 25 years, as she was completing her current project in New York. The film that spoke to Mildred, for what it said about the past, continues to speak to her daughter, for what it says about the present.

“As I came out from work, all these demonstrators — spurred by police brutality in Ferguson, Missouri and Staten Island — were walking down Canal Street, blocking traffic,” she says. “Didn’t we have a civil rights movement? Are we still struggling with this? God, it’s horrible. The notion that we could state the problems of race and poverty in Places in the Heart without one ounce of cynicism is remarkable. There’s a basic humanity that Americans share, and that is so rarely pictured onthescreen.”