by Peter Tonguette • stills courtesy of Columbia Pictures

Over the course of her long and accomplished career, assistant editor Christy Richmond has attended her share of screenings for studio executives. Sometimes, the higher-ups respond favorably; other times, their reactions are less than what the filmmakers might have expected.

“If it’s a comedy, a lot of times people don’t laugh,” Richmond comments. “If it’s a heartfelt film, it looks like it’s not touching them at all.”

Photo by Deverill Weekes

Occasionally, however, a film is received in just the right way. Such was the case when writer-director Bruce Joel Rubin’s My Life (1993) was screened for executives at Columbia Pictures. “I’ve never worked on a film quite like that — not before or since,” says Richmond, who served as the first assistant editor under picture editor Richard Chew, ACE. “It seemed to touch everyone who watched it where they lived.”

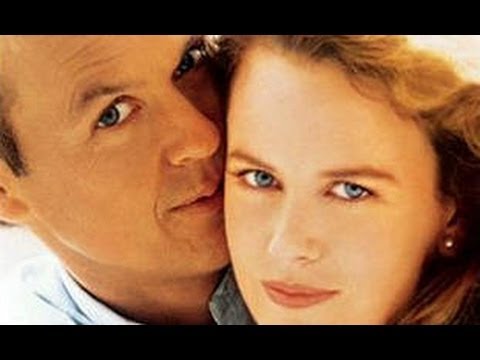

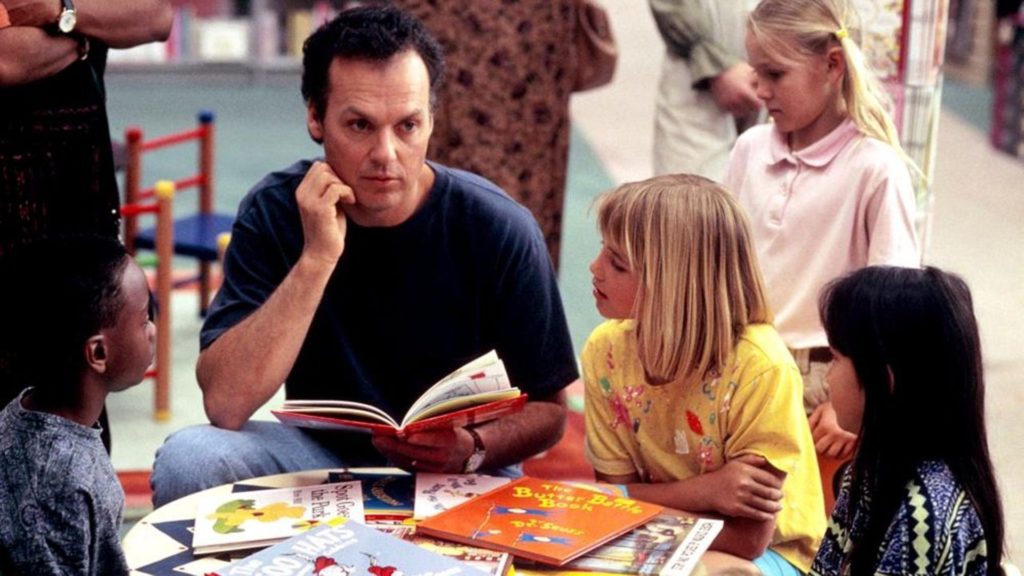

The drama revolves around business executive Bob Jones (Michael Keaton) who grapples with mortality in the aftermath of a terminal cancer diagnosis. As he fights for his life through alternative therapies, Bob reckons with the past and looks to the future. In videos recorded with his camcorder, he candidly addresses the unborn child he is expecting with his wife, Gail (Nicole Kidman).

Richmond remembers the reactions and comments from the Columbia executives when they viewed the film. “Afterwards, we’d go out in the hall and usually they would all hug Bruce Joel Rubin,” she recalls. “I remember hearing one executive saying that he was going to go right back to his office and call his parents. It really touched a lot of people in an unbelievable way…and yet so many people have not seen it.”

Indeed, My Life did not break box office records upon its release. Despite the presence of Keaton — just a year removed from his stint playing Batman for director Tim Burton — the film earned just under $28 million in the US. Yet its continued popularity on home video has validated the executives’ responses.

“When people heard that I worked on the film, they often said, ‘Oh, that must have been a depressing film to work on,’ but I said, ‘It was not depressing — not at all,’” the assistant editor stresses. “But everyone who actually went to see it, or watched it on DVD, has said to me, ‘You were right. There was nothing depressing about that movie. It was uplifting.’”

A native of Texas, Richmond was a film buff from an early age. As a middle school student, she worked part-time at the concession stand of a local movie theatre, sometimes peeking in to check out the featured attraction for free. “When Bonnie and Clyde [1967] was playing, I watched the ending, when they’re killed, over and over again, because I was fascinated by the way it was put together,” Richmond recalls. “I didn’t realize what it was that fascinated me, but later on I realized it was the way it was edited.”

Richmond attended the University of Texas at Arlington, where she earned a degree in English Literature in 1980. One of her favorite professors suggested that she consider editing, rather than writing, as an occupation. “I began to really watch how scenes were edited,” Richmond says. “I wanted to see if I could figure out what they had done, watching them cut from wide shots to close-ups and complementary angles. It had never occurred to me, ‘Oh, this is a craft by these incredibly talented people.”

After reading noted editor Ralph Rosenblum, ACE’s 1979 book When the Shooting Stops…the Cutting Begins, Richmond wrote a fan letter asking for the Annie Hall editor’s advice. “Apparently, editors don’t get a lot of fan mail because he wrote me back and gave me some encouragement,” Richmond recalls. “He said, ‘If you’re serious, you should either move to New York or Los Angeles. There’s more work in LA right now, and the weather is a lot nicer.’”

So, in the fall of 1980, Richmond loaded her belongings into a U-Haul truck and relocated to Los Angeles. While working at a supermarket, she volunteered her time synching dailies on a student film made at the American Film Institute. “Then someone gave my name to someone else, and I kind of went from there,” Richmond offers. “I was lucky enough to get into the Editors Guild in just a few years.”

In the early days, Richmond accepted assignments as both an assistant picture and sound editor; it was while working as the latter on Martha Coolidge’s Real Genius (1985) that she began what became a three-film working relationship with editor Chew. “Sometimes people revere editors so much — which I do, too — that they are afraid to ever say anything to them, but I was never like that,” Richmond explains. “Richard liked my sense of humor and my enthusiasm, and he hired me.”

By the time of My Life — which Chew cut on a KEM at Sony Pictures Studios, where the film was also shot — the duo had settled into a routine. “When people ask, ‘What does an assistant editor do?’ I always say, ‘We do everything so that the editor only has to cut,’” Richmond says. “We manage everything that comes in and everything that goes out.”

During the screening of dailies on My Life, Chew told Richmond which takes he preferred. “He would lean over and whisper in my ear,” she relates. “I would take notes for him in the dark. By the time he had viewed the dailies, he had pretty much cut the scene in his head.” Chew marked takes with a grease pencil, indicating the ins and outs of where he wanted picture and sound to be cut. “He gave me a sheet of paper with the takes listed in order, and he numbered all the cuts,” Richmond recalls. “I took that and helped build the scene with him.”

Rubin, who had won acclaim for writing such emotionally intense movies as Ghost and Jacob’s Ladder (both 1990), made his first foray into directing with My Life. “Bruce leaned on Richard a lot,” Richmond observes. “If he remembered a take that had a different emotional tone, or a different performance in it, then they would look at that and decide which one to use. They seemed to mesh really, really well.” Ghost was directed by Jerry Zucker, one of the producers of My Life.

The director also invited input from Richmond, which led to a memorable exchange between the director and assistant editor. “When we were working on the director’s cut, Richard left the room and Bruce said, ‘Now, I want to know what you think about the scenes, too,’” Richmond recalls. “I said, ‘Well, that’s not really how this works. If you would like to know what I think, feel free to ask me, but I won’t offer it unless I’m asked.”

Even so, Chew gave Richmond the opportunity to work on editing a pair of scenes — albeit ones he did not expect to make the final film. “Before a frame of film was shot, he could go through the script and say, ‘This scene and this scene won’t be in the final cut,’” she recounts. “I would say, ‘How do you know that?’ And he would say, ‘I just do.’ But everything has to be cut.” In fact, portions of Richmond’s scenes — depicting Bob visiting a toy store and reading from Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham — did make the final version of the film.

To indicate to audiences when the film was shifting from straightforward dramatic scenes to excerpts from Bob’s videotapes, Chew came up with the idea of briefly cutting to black before and after each transition. “The audience needed to know that this is tape, or that now he’s cut the tape off,” Richmond explains. “I forget how many frames it was — two or three — but we tried it a number of times to see what amount felt right.”

My Life was scored by Academy Award-winning composer John Barry — one of Richmond’s favorite composers. “I had so many CDs of his scores — Somewhere in Time [1980], Out of Africa [1985],” she says. “When we went to the scoring stage, I worked up the courage to bring some CDs and, if I got a chance, I was going to ask him if he would autograph them for me. His wife saw them and said, ‘Do you want John to sign?’ I said, ‘I do, but I do not want to bother him…’ She pulled him right over and he said, ‘Of course, my dear, of course.’”

Because the film was photographed and edited on the same lot, a family atmosphere pervaded the production. “Nicole Kidman was married to Tom Cruise at that time, and they had adopted their first child,” Richmond recounts. “She had the baby on set with a nanny.” Easter was celebrated while shooting was still ongoing, so Kidman had her assistant make Easter baskets for each member of the crew. “That meant she had to make something like 350 of them,” she explains, “and the baskets included a handwritten note from Nicole.”

Yet despite the friendliness of the set — and the sincere responses from the executives who had given the film the greenlight — the public did not turn out in large numbers for My Life. “When someone actually saw the film, they had an emotional reaction to it and they really liked it,” Richmond says. “But first you have to get — as they say — the butts in the seats. It was such a special film.”

Richmond worked with Chew once more on Forest Whittaker’s Waiting to Exhale (1995). For his part, Rubin has yet to direct again, but Richmond remains in contact with him via Christmas e-mails — and by occasionally encountering him while out and about in Los Angeles. “After the show was over, Bruce said to us, ‘If you run into me 20 years from now and I don’t remember your name, please forgive me,’” Richmond remembers. “Whenever I run into him, I always say, ‘Hi, I worked on My Life…’ In the middle of my explanation, he says, ‘I know who you are, Christy.’”