By Rob Callahan

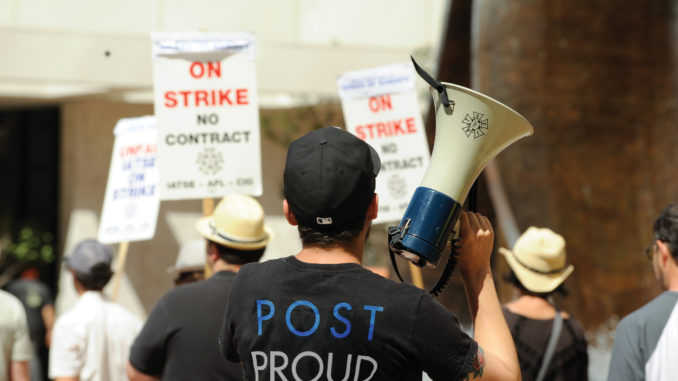

On the morning of Monday, November 18, not long before their employer was due to deliver a two-hour special of the reality TV show Naked and Afraid to the network, assistant editors and editors working on the show walked off the job together. They emerged from their dim edit bays and congregated in a clutch on the sidewalk outside the company’s Sherman Oaks offices, eyes blinking against the unfamiliar sunshine and their own brazenness.

As they huddled, the crew members shot nervous looks at one another, seeking reassurance in hastily exchanged glances. But mingled with their nervousness was a nascent giddiness as they came to have a real sense of their own power. They understood that their labor was instrumental in creating a hit show, and they understood that, if they stood unified, the show could not go on without them.

Those who follow my bi-monthly bulletins in CineMontage might remember my reporting herein on our successful campaign in early 2013 to win a contract for the crew of the show Swamp People, a docu-reality-style program produced by Original Media for the History Channel. The Swamp People victory represented a noteworthy variation upon the slew of success stories the IATSE has racked up in reality TV over the past three years, in that the effort was fully driven by post-production employees.

As a campaign led by the editorial crew, Swamp People offered a model for organizing the run-and-gun style shows that previously had largely eluded organizing approaches oriented towards disrupting shows’ shooting schedules. Swamp People’s editors and assistant editors demonstrated that, even if a non-union show doesn’t employ the sort of large production crew conducive to organizing efforts, we can fix it in post.

The post crew of Naked and Afraid, a new series produced by Renegade 83 for the Discovery Channel, had taken the lesson of Swamp People to heart. The show’s premise is to chronicle the ordeals of contestants tasked with surviving three weeks in a remote wilderness, without gear or clothing. The show employs bare-bones shooting crews operating in far-flung locales, but employs a large post-production crew, operating out of Renegade 83’s office, to fashion stories from the accumulated footage.

After the Discovery show’s initial seven-episode run scored strong numbers for the channel and the network renewed the series with a large order, individual editors and assistant editors decided that they merited a better share of the show’s success. A series of quiet conversations ensued, in which crew members assessed the degree of colleagues’ support for organizing and the degree of leverage they had vis-à-vis their employer. Determining that they had both the will and the way, the crew arrived at a consensus to take action.

The issues motivating this crew’s desire for a union contract were much the same as those that generally inspire non-union crews to organize. Folks felt that a successful show ought to be able to provide health and retirement benefits to the people whose labors help to make it a success. They wanted contractual guarantees of overtime pay in order to provide a disincentive for the company to schedule people to work interminable hours. And the assistant editors sought wages that would better reflect the skills and effort they brought to the job.

Unlike many reality shows, which tend to employ a high ratio of editors to assistants, Naked and Afraid relies upon a large crew of assistant editors. Assistants working on non-union, unscripted television are often poorly paid, and that was especially the case with the AEs working this show. Despite college degrees and technical acumen, they had the sort of low-wage jobs more typically associated with the fast-food industry than with the motion picture industry. Working 60-hour weeks, their effective hourly wages were generally a little better than they might have received working at McDonald’s, but (factoring in benefits) generally a little worse than they might have received working at In-N-Out Burger.

Editors, on the other hand, enjoyed dramatically higher wages, as is frequently the case in unscripted TV. People often assume, sometimes rightly, that such a gulf — the gap that separates, on the one hand, twentysomethings with only a couple of years’ experience earning fast-food wages as assistants from, on the other hand, fortysomethings with a couple of decades in the business earning perhaps seven times those hourly rates as editors — presents a formidable barrier to organizing. How much can folks on the low end and folks on the high end of this range really have in common? And how can they bridge the distance between them to forge solidarity?

However much their levels of experience and the sizes of their paychecks might have differed, the assistants and editors of Naked and Afraid, like so many members throughout our union, recognized that they shared fundamental interests. This assistant might have chiefly been concerned with paying off student loans, or with being able to afford an apartment with a few less roommates. And that editor might have been focused on making sure a child had access to the best medical care, or on making some provisions for the retirement years that were no longer seeming so unimaginably far off in an impossibly distant future. But both understood that in order to make sure their jobs better met their respective needs, they needed to stand together. Which is exactly what they did on that Sherman Oaks sidewalk on the morning of November 18, huddled in the glare of a brash Southern Californian autumn morning.

The strikers took confidence from all the allies who came to their defense. Chiefly, though, they took confidence from one another. Editors and AEs alike.

Thus began a strike that lasted for six days. Those six days were largely uneventful, but were nevertheless grueling and anxiety-filled for folks uncertain of when (or if) they might return to work. For days, negotiations plodded along without any significant evidence of progress, while the company and network, facing a looming airdate that had been heavily promoted on the network, weighed their options.

In the meantime, Guild members from all over LA — joined by scores of sisters and brothers from other IATSE locals — came out to walk the picket line in support of the striking crew. Several members of the Swamp People crew, having intimate knowledge of the anxieties that attend any struggle of this kind, stopped by to offer their encouragement and wisdom.

The strikers took confidence from all the allies who came to their defense. Chiefly, though, they took confidence from one another. Editors and AEs alike, they recognized that they needed one another, and they recognized that, together, their employer needed them. The certainty of each individual’s commitment to the entire crew carried them through the uncertainty of the six-day waiting game.

At last, the Saturday after their strike began, the company agreed to sign a union contract to return folks to work. The agreement provided for health and pension contributions retroactive to the beginning of the month. It preserved over-scale rates for the editors, and for most assistant editors it effectively doubled their hourly rates. It guaranteed that the show’s production crew would enjoy the protections of an IATSE contract in future seasons. And it added another, hard-won title to the growing list of union reality television shows.

When strikers returned to work following the Thanksgiving holiday, they donned Local 700 T-shirts in a display of their enduring solidarity. The show’s title notwithstanding, this crew had proven itself clothed and courageous. We all owe them a debt of gratitude, a debt best repaid by honoring their example, by standing up for ourselves and standing up for one another.