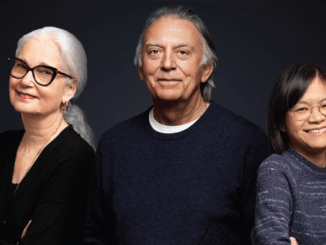

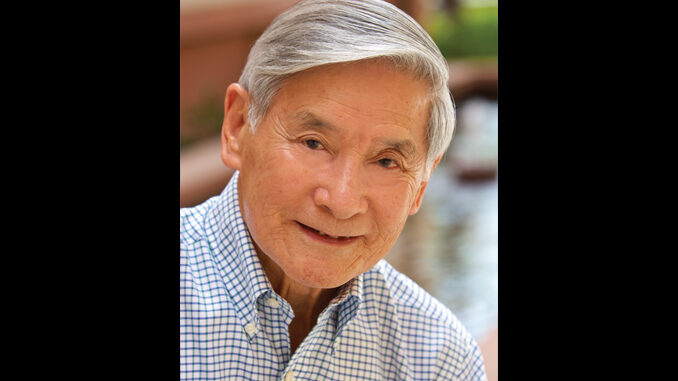

by Mel Lambert • portraits by Wm. Stetz

During a busy and productive career that spans 60 years in film and television, sound editor Don Hall––the 2011 recipient of the Editors Guild’s prestigious Fellowship and Service Award, to be presented to him at a ceremony scheduled for October 15––has collaborated with a number of prominent directors. Among them are Otto Preminger, Robert Wise, Arthur Hiller, Mel Brooks, Robert Altman, William Friedkin and John Frankenheimer. Hall’s impressive resume includes over 90 credits in both features and TV, including Patton, The French Connection, Towering Inferno, Young Frankenstein, Single White Female, A Walk in the Clouds, M*A*S*H (the film and the series), Land of the Giants, Lost in Space, The Love Boat, Charlie’s Angels and Barnaby Jones.

Following a full and active career as a sound editor and administrator, Hall is currently enjoying a second career as a senior lecturer at USC School of Cinematic Arts, where he teaches sound design, production sound, sound editing and mixing (see sidebar, Page 19). He also serves as a mentor for graduates pursuing an MFA in Film and TV Production with an emphasis in sound design.

“In the early days, I was not as philosophical as I am today; I was maybe more intuitive.”

His work has been honored with Emmy Awards for Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and Tribes, and a Peabody Award for Excellence in Television for the M*A*S*H series. He received a British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award for his outstanding work on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. In addition, both the Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE), of which he was a founding member, and the Cinema Audio Society (CAS) have honored him with several awards for film and television projects.

In 2004, Hall received the MPSE’s Career Achievement Award and, in 2006, was honored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences (AMPAS) with the John Bonner Medal of Commendation, the Academy’s highest honor given to a person in the sound field. He has served on the Academy’s Board of Governors, representing the Sound branch, for going on 16 years. Additionally, in 2002, he went to Vietnam to teach production sound recording through an AMPAS/Ford Foundation program.

Following graduation from the Art Center College of Design in 1951, Hall married Teddy Tang (they celebrated their 60th anniversary this year!) and took his first job as a director of photography and film editor with Mercury International Pictures. From there, he became an assistant film editor at 20th Century-Fox Television with Art Seid. In 1956, Hall became a sound editor for Federal Television, working on the Goldwyn lot in Hollywood.

“In those early days,” Hall recalls, “we shot TV shows on film and edited sound with optical tracks, but were transitioning to 35mm mag with an optical sound track printed on the opposite side. While we became used to scrub- bing mag film over the heads, older editors needed to see the optical modulation. Of course, it is much faster now on workstations––where you can see the modulation on the monitor.”

Photo courtesy of Don Hall

Why the change from picture to audio? “I needed to make a choice,” Hall replies. “When Mercury International Pictures was unionized, I was given a choice of memberships in both Local 776 [now Local 700], the Editors Guild and Local 659 [now Local 600], the Camera Guild. I couldn’t afford to join both, so I chose picture editing because I wanted more freedom

and thought that the cutting room would give me that.” Unbeknownst to Hall, there was a seniority system in effect then; everyone had to come in to the Editors Guild as an apprentice and could not cut picture until eight years later. “But you could be an assistant editor after 18 months, and cut sound after three years,” he says. “Because I came from a company that was unionized, the Guild allowed me to move to sound in a shorter time.”

Hall found that a previous knowledge of picture editing was very useful when he made that transition. “I understood the role of picture editors and their problems in editing film,” he explains. “There were some editors who cleaned up their sound tracks; others just hacked it. Some picture editors were very sound- conscious and wanted a clean track for their screenings; they looked for better readings to improve performance. At Goldwyn Studios in Hollywood, Gordon Sawyer––the head of the sound department––took me under his wing and trusted me with several films, including Porgy and Bess and The Alamo, which helped build my reputation and show directors that I could probably handle bigger movies.”

Having worked as supervising sound editor on independent features, Hall moved to 20th Century-Fox in 1965 to become the supervising sound editor for Irwin Allen Productions, working on Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, Lost in Space, Time Tunnel and other offerings. Soon after, the feature and television sound editing departments were combined and Hall became the supervising sound editor for all Fox productions. “My approach was hands-on,” he recalls. “I edited alongside my crews and worked with the mixers on all major features and TV series.”

In the mid-1970s, Hall moved across town to become post-production supervisor for several television companies, during which time he worked for Quinn Martin, Spelling-Goldberg Productions and Aaron Spelling Productions. I first worked as post-production supervisor on The Love Boat––something I had not done before––overseeing all elements of sound and picture in post-production,” he relates. “TV in those days was more leisurely than it is today. We had maybe three weeks to complete a one-hour pro- gram. But we tried to keep the quality as high as we could; we just treated it like a film mini-feature.”

An Intuitive Approach to Sound

Hall’s sound philosophy and operational techniques have changed little during his long career. “In the early days, I was not as philosophical as I am today; I was maybe more intuitive,” he admits. “But I always like to work closely with the director and have a spotting session with him. To learn his ideas about what he hears in the film soundtrack. To understand the overall vision, and what will best tell the story, taking into account the story arcs and what the musical score will be doing. I then turn this into a process or series of tasks.”

Many directors in those days were not very sound-conscious, according to Hall. “They could not make judgments on sound until they heard the track,” he remembers. “For me, a critical part of formulating a TV or film soundtrack was to attend the dailies every day and hear the director’s comments. We then had a good idea of what the film was about and could conceptualize the soundtrack. But, normally, we had very little to do with the production mixer. Back then, it was unusual for a post-production person to be on the set.

“For The Alamo and Butch Cassidy I was able to go on location and record sound effects,” he continues. “On The Alamo, I got 30 horses and a platoon of soldiers with flintlock rifles, and proceeded to record some great sounds. At that time, [director] John Wayne was aware of how important sound was for his picture. For In Harm’s Way, with Otto Preminger, I was on location from the first day of production, and recorded numerous sound effects aboard the heavy battle cruiser, St. Paul. This all came about when we sailed from Seattle to Pearl Harbor. No women were allowed aboard ship and Preminger informed me that I was to be the script clerk. So Kathleen Fagen, our script super- visor, enjoyed two weeks on the Waikiki beach!”

In 1986, Hall was named vice president of post-production at Walt Disney Studios in Burbank. “That was basically an executive position––‘a Suit,’ if you will,” Hall recalls with a wry smile. “I thought it would be a good opportunity to work with the Disney Studio; it was another step to follow on my career path. I wasn’t handling sound, mostly supervising. In 1990, I became department head of editorial at Disney, which just doubled up on the duties.”

Three Key Criteria for Sound Editors

Regarding what it takes to be a good sound editor, Hall identifies three key criteria: “The first thing is Ability––which, by that time, applied pretty much to everybody I saw. The next aspect would be Dependability––we work on very tight schedules, and you need to show up on time and deliver against tight deadlines. And, finally, Loyalty––something we build as a new hire starts working for me. So that they can see and hear how it has all come together, I have my sound editors come to the stage when it is time to mix their reels; that provides a great learning experience.”

Although Hall has seen major changes in the technologies used for sound editorial and mixing, an ability to make creative decisions is still a vital parameter. “When digital first came out, you could manipulate sound so much that we thought it might destroy the thinking process for both picture and sound editing,” he reflects. “In the old days, before you reached for the scissors to cut that picture or track, you thought about it. How was it going to play? How was it going to affect this current cue? And where is the next cut going to be? That, for me, was a very important part of the thinking process. As it turns out, editors can now do 20 options in two minutes on a work- station and find the one they like! That’s the way they are trained––to experiment.

Which is the best edit; this one or that one?”

Looking back on his long career, Hall considers that three directors had a major impact upon him: “The one film I had the most fun with was Young Frankenstein, with director Mel Brooks. He was open to ideas, but not somebody you could satisfy––because his ideas came to him as he was sitting in the mix room! He also did Silent Movie on the Goldwyn lot, where we had to keep the Foley stage open to record new sounds. Mel was very unregimented; very spontaneous!

“I worked with Otto Preminger on Porgy and Bess early in my career and we became very good friends. I repeated with him on In Harm’s Way. But he was a tyrant; Otto had to fire somebody every day. He really had a mean streak, but also had a soft side to him.

“William Friedkin was very demanding. I worked with him on The French Connection, where pretty much everything had to be re-cut. It was a horrible experience at the time because I had a makeshift crew. I sensed where he was going; I could see he knew the sound he wanted. It was truly a learning experience for me, I’m forever grateful for it.”

In fact, Hall is grateful for a lot. “I have many to thank for the successes I have enjoyed during my long career, beginning from supporters at the beginning and each and every one who has worked beside me,” he says. “Ours is a collaborative business; the work is only as good as those who surround you.

The Guild Connection

“Of equal importance,” Hall continues, “is the organization that supports and protects us: the Motion Picture Editors Guild. I feel qualified to make comments from several viewpoints: studio management, owner/operator and working editor. I came into the union in 1952, a year of significant importance for IATSE as the MPIHP [Motion Picture Industry Health Plan] was formed, followed the next year by the MPIPP [Motion Picture Industry Pension Plan]. They are the premier health and retirement plans that we rely on so heavily today.” In 1990, the separate plans merged into the Motion Picture Industry Pension and Health Plans (MPIPHP).

On the labor side of the equation, Hall cites other advancements: “The eight-year rule to become an editor was subsequently eliminated altogether and the scale rate has steadily increased in all classifications, thereby protecting our members from being underpaid by low-ball filmmakers. I would also include the following in our successes: elimination of the six-day work-week, penalties for employers overworking our members, limits to consecutive days on the job, and hands-on classes for members to stay current as technology changes. In other words, our Guild sup- ports and protects its members, a fact that’s easy to forget in our day and age.”

Even in his current role as a teacher, Hall emphasizes to his students the importance of being a member of the Editors Guild to succeed. He also instructs them to document all of their hours accumulated working on non-union projects, to qualify for membership.

Regarding his selection as this year’s Fellowship and Service Award honoree, Hall remarks, with no sense of false modesty, “Every award that comes to me is a surprise––like this one from the Guild. It helps define the importance of sound in filmmaking.”