By Peter Tonguette

William Friedkin was in the editing room as he was in life: blunt and bold, volatile and sometimes volcanic.

The Oscar-winning director of such modern classics as “The French Connection” (1971), “The Exorcist” (1973), and “To Live and Die In L.A.” (1985) died Aug. 7 at age 87.

The Chicago native first received attention as a maker of documentaries and then helmed a series of acclaimed art-house films, including adaptations of Harold Pinter’s “The Birthday Party” (1968) and Mart Crowley’s “The Boys in the Band” (1970). He discovered the power of connecting with a wide audience with “The French Connection,” which, in telling the story of Detective Popeye Doyle’s (Gene Hackman) relentless tracking of French drug kingpin Alain Charnier (Fernando Rey), featured an unusually visceral, in-your-face chase scene. Undoubtedly, the editing of that iconic chase contributed to the Oscar win of picture editor Gerald B. Greenberg, ACE.

Subsequent Friedkin films featured dazzling displays of intense, unnerving, altogether unexpected editing, including in the multi-character trial of wills “Sorcerer” (1977), edited by Bud Smith, ACE, and Robert K. Lambert, ACE, and the strikingly complex serial-killer film “Rampage” (1987), edited by Jere Huggins.

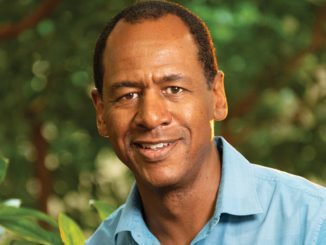

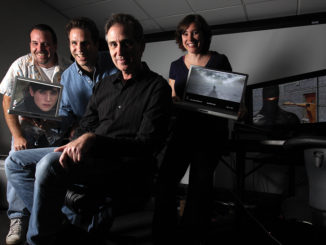

Since the mid-1990s, Friedkin worked almost exclusively with two editors: first, Augie Hess, who edited Friedkin’s high-profile Paramount features “Jade” (1995), “Rules of Engagement” (2000), and “The Hunted” (2003), as well as several TV projects; and then, Darrin Navarro, ACE, who, after beginning as Hess’s assistant on those films, went on to cut Friedkin’s intriguing indie features “Bug” (2006) and “Killer Joe” (2011), as well as the filmmaker’s final effort, an adaptation of Herman Wouk’s “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” set to premiere this month at the Venice Film Festival.

After Friedkin’s death, CineMonage spoke with Hess and Navarro about working with one of the most distinctive of all American directors.

CineMontage: Augie, how did you come to work with William Friedkin?

Augie Hess: I’ve been an editor for 35 years in Hollywood. In the 1990s, electronic editing was coming into Hollywood, and I decided to jump out of the editing realm and go work for hardware manufacturers of editing systems. I got scooped up by Lucasfilm, and we were developing a system called EditDroid. One thing led to another, and I moved to another company called Lightworks. Everybody was slow to adapt, but Billy was one of the people who recognized the potential of electronic editing.

CineMontage: You first worked with him on his 1994 basketball drama “Blue Chips,” starring Nick Nolte and Shaquille O’Neal.

Hess: I was sitting with the president of Lightworks and said, “I’ve really got to go back to what I love — editing.” They said, “Well, there’s this storm going on over at Paramount that we know about. Friedkin is trying to cut this stuff on his sports movie, and he’s churned through a whole bunch of editors over there.”

CineMonage: “Blue Chips” was edited by Robert K. Lambert and David Rosenbloom, but you came on to work on the basketball sequences.

Hess: They had put 13 cameras in a circle in the arena and shot all the basketball sequences without a script. It was like: “All we know is Nick Nolte has to get thrown out in the second quarter.” Billy was trying to cut it on film, and they just weren’t moving fast enough for the way he wanted to work. When you’re cutting freeform spots, in multiple takes and zillions of cameras everywhere, the slowness of film editing just wasn’t cutting it. I knew the electronic hardware really well, because I was involved in the development of it, so we made sense out of it.

CineMontage: What was Friedkin like to work with?

Hess: He was extremely demanding, and if you weren’t performing at the level and speed that he was expecting, he moved on. I was the last guy standing after the war on that one. He was in pretty strict control of everything that went on with his cuts. You just had to know where the material was and be able to get it to him as fast as he needed it. He wanted immediate access to everything that there was.

He didn’t like cuts being in predictable places. In other words, one of the things that you often strive for in editing is to make the editing disappear: somebody finishes the line and the next person speaks, and you cut to it right away. Billy was always most interested in making unpredictable cuts that, in his mind, were better. His films were never slow. There was no problem in sacrificing something if it wasn’t working. He was the first one to say, “This isn’t working. Throw it away.” We weren’t stringing together the performances from the actors. We were taking it to the next level, shaping it and sculpting it. It was wonderful and a joy to witness.

CineMontage: After “Blue Chips,” you edited Friedkin’s TV movie “Jailbreakers” (1994), starring Shannen Doherty. What was that like?

Hess: I survived the big movie with him, and then he had this little thing coming up. I was a natural fit to go on with him, so we did a whole movie, from end to end, and glommed onto each other for about 10 years. But he didn’t have the low-budget version and the high-budget version. He did it in the way that he wanted to do it. It’s what a director is supposed to do. He was the classical, egotist director that you can’t say no to. He made his films fearlessly.

CineMontage: The first feature you cut for Friedkin was the thriller “Jade,” starring David Caruso and Linda Fiorentino. Friedkin wrote in his memoir that the car chase in that film was his own favorite.

Hess: Much of it was shot up in San Francisco, and I was on location with it. The car chase is like 10, 11 minutes. It was just relentless. I remember the call sheets. The call sheet on Monday might be, “The car comes around the corner at Chinatown,” and it was an eighth of a page continued from Friday. Directing is running the set, and he would truly control the set. I got the feeling that he knew everything about the lighting that the lighting guy needed to do. The stunts in the car chase were probably the biggest and most exciting stuff that we did there, and we had everything from car jumps to smashing into other cars and throwing them into the river.

CineMontage: How did you get it to cut together?

Hess: You don’t have all the pieces as you go because he was shooting little bits and pieces a day. They would come in over a long period of time, and it wouldn’t necessarily be in order. It was kind of like creating this patchwork quilt.

CineMontage: Darrin, you worked with Augie and Friedkin during all of these years. How did it start?

Darrin Navarro: I was on “Blue Chips” as a second assistant editor for a couple of months. I never really crossed paths with Billy on the film. About a year later, Augie emerged from the ruins of the “Blue Chips” editorial crew to take over the role of Billy’s favorite editor. Augie hired me onto “Jade” based on the recommendation of other editors but really based on the fact that I had any experience on one of Billy’s films, regardless of my proximity to Billy himself.

CineMontage: Augie, you next edited Friedkin’s TV remake of “12 Angry Men” (1997).

Hess: To make an entire movie stuck in the same set interesting all the way through was a real exercise. He would shoot coverage handheld, then he’d shoot it with Steadicam, then he’d put the cameras on cranes. He was never really one to ever be interested in a tripod. Everything had to have an edge of movement to it.

Navarro: The handheld nature of it kept it alive. It’s supposed to be a very hot day. It has a little bit of that ’70s, sweaty, jittery quality of his heyday.

CineMontage: What do you remember about the military drama “Rules of Engagement,” starring Samuel L. Jackson as a Marine who defends a U.S. embassy in Yemen and faces trial back home for his actions?

Hess: His memory was excellent. On “Rules of Engagement,” there was a shot that he knew he made but he couldn’t find in the dailies. I said, “What’s it a shot of?” He said, “It’s a shot of the camera tilting from all the protestors down below back up to the guys firing the machine guns. I’m not leaving Morocco until you find this shot.” We looked at all the dailies back in LA, and it wasn’t there. I took all the trims and said, “Show me everything from when the camera turns on to when the camera turns off that was trimmed out for screening dailies.” It was at the end of a take after cut and it had been trimmed off. I sent him a copy of the shot and he said, “You’re brilliant. OK, we’re moving on.”

Navarro: The assault on the embassy was one of the most extraordinary stagings that I had ever worked with in the editing room as an assistant or as an editor. I don’t even remember how many cameras they had running. They basically just staged that whole event, obviously in pieces, but it was pretty much as you see it. They brought in three helicopters every take, plus there were helicopters with cameras on them. The assassins on the roof, the crowd down below, and the Marines coming through — it was all staged multiple times.

CineMontage: Darrin, why do you think Augie and Friedkin got along so well?

Navarro: Augie is a terrific editor. He is just a very, very astute editor of drama. He had a command over the material, and he managed the room in such a way — and left me to manage the other assistants — that nothing fell through the cracks. That was the thing that had always tormented Billy on previous editing rooms. He came to us really early on and said, “Darrin, I’ve just got to tell you that I haven’t been in a room that has been this reliable in many years, so thank you.” 95 percent of the time, Billy was the most cordial director I’ve ever worked with.

Hess: You can hear the stories of how he controlled a room and stuff like that, but what he did was he responded to preparation. If you were slacking in any way, he would just blow up at you. You were on the edge all the time, but the longer we worked together, that loosened up a little bit.

CineMontage: Augie, you edited one more feature for Friedkin, “The Hunted,” starring Tommy Lee Jones and Benicico Del Toro. After so many films, what had become your and Friedkin’s process?

Hess: I would cut everything and be ready to just throw it out with no ego involved. I kept up with the dailies because it was the only way for me to know the film well. But there were a lot of circumstances where he would never even see my cut. He would say, “Let’s just sit down and look at the dailies.” That was our process, and it worked well for both of us.

Navarro: Despite what a lot of people may think, he was actually a very receptive and porous filmmaker. He was interested in his collaborators, he was interested in what the studio had to say. He wanted sincerely to make movies that were going to be seen by a lot of people.

Hess: He was very in tune with the audience. Much of that is just the feel of putting it in front of an audience for the first time. You can tell when you’re in the room where the energy just sags or if they’re losing interest. Screenings were important.

Navarro: “The Hunted” really felt like Billy working with barely a sketch of a script but, in a weird way, allowing that to give him the freedom to become a visual storyteller, which nobody could do like he could. That movie, to me, had a kind of artfulness that a lot of action films don’t even try for. There was a dreamy, nightmarish quality to the movie in general, and I said to Billy, “This feels like it’s in conversation with Terrence Malick.” And he recoiled! I think he had a knee-jerk revulsion to the idea of making art films, yet he made art films from time to time.

CineMontage: Darrin, after Augie moved on, you found yourself in the position to cut the first of Friedkin’s two adaptations of Tracy Letts plays, “Bug,” starring Michael Shannon as a man whose mind has been preyed on by conspiracy theories, and then “Killer Joe.” These were, in fact, art films!

Navarro: It was probably the right movie to join Billy on. Billy was going back to something. He had done theatrical adaptations before — “The Boys in the Band” and “The Birthday Party” were both stage-to-screen adaptations that he had done pre-“French Connection” — and after the blockbuster success of some of his movies in the ’70s, on some level he was chasing that kind of mass appeal the whole time with varying degrees of success. When he saw “Bug” Off-Broadway in the early 2000s, it lit a fire in him that probably hadn’t been there for a while.

‘This movie will be widely hated!’ He was almost giddy.

After I had spent all of those years as an assistant on those films at Paramount, we were working on “Bug.” I had done my cut, and he had gone through and done his pass on it. We sat down and looked at the whole thing, and about halfway through it, I heard him giggling behind me on the couch. We were laughing a lot at the movie, because we did regard that movie as a very, very black comedy, but he was laughing at something else. He just looked at me with this big smile on his face and he said, “This movie will be widely hated!” He was almost giddy. He now had the freedom to do that.

CineMontage: What was Friedkin trying to accomplish in the editing on these films?

Navarro: Surprise. He wanted things to be unexpected. He also loved ambiguity, and in his best movies, he was always able to achieve an ambiguity of meaning and even an ambiguity of events. He didn’t want you to know exactly what happened. He wanted you to be reaching for it. Certainly we were able to do that with “Bug.”

CineMontage: How did you make these plays work cinematically?

Navarro: With “Bug,” it was so confined — 90 percent of the time, just this one motel room divided into four quadrants — that it was really important to him that it be cinematic. It was a built set, so every wall and the ceiling could be moved. The camera could go anywhere. It was really important to him that no two scenes in the film have the same camera scheme. The lighting also changes throughout the movie. The early scenes are very yellow, we move through a very red phase, and we get into the blue phase.

Our cutting style changed throughout. All the jump-cutting early was a way of just telling the audience, “This is not a play, this is a movie.” When we’re compressing time like that, by jumping Ashley Judd across the room or clearly cutting time out of a phone call, we’re sending a message to the audience. That gave us the freedom to do later scenes where we play longer takes.

CineMontage: Augie said he would prepare his cut but then start over. Is that how you usually worked?

Navarro: We would do the cut ahead of time before he came in so that we knew the material, but when he came in, we would just start with Scene 1 and we would edit it from dailies. We would refer to the existing cut if, for any reason, we got into trouble. Billy was always a little bit reluctant to look at something that had already been cut.

On “The Caine Mutiny-Court Martial,” however, we had started that process and, about two days into it, there was a scene that he knew we had trouble with. Billy was trying to get everything in one take, and early in the shoot, some of the blocking just didn’t work. We had trouble with how the prosecutor was moving around the room and where the witness was looking. I said, “For this scene, we should probably look at what I have, because I’ve done the best I can do with the footage that I have.” He looked at it and said, “It looks great. What else you got?” We looked at the next scene and he said, “It’s terrific, let’s do the next one.” He left the room, and left me with a half-a-dozen little notes. We were done three days into the edit.

CineMontage: Why do you think that was?

Navarro: We had worked together a long time, I knew his style, and we talked a lot about how he wanted this cut. He also really did shoot most of it in one or two takes, so he knew there were not deep reserves of footage that were unseen. It was a different kind of project, and it was the right project for him to lift his hands from the day-to-day work and trust other people.