By Betsy A. McLane

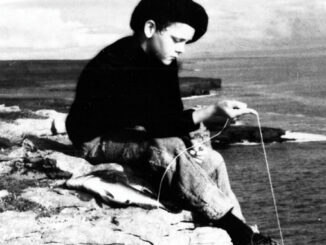

The obituary headline for Helen van Dongen in The Guardian of London read, “Pioneering Film Editor Who Left Her Stamp on a Generation of Early Documentaries.” When she died in October 2006 at the age of 97, van Dongen had been in self-imposed retirement from the film world for over 50 years. Her work is remembered almost solely by specialized historians, and her personality recalled by only a few remaining professional associates. For those who love documentary and know the many values that editing brings to a film, van Dongen deserves to be celebrated now, and always, as a great contributor to the art of documentary.

Van Dongen, as are most good documentarians, was masterful in many aspects of film- making. She was admired as much for her innovations in sound editing and design as she was for picture edit ing. She was born in Amsterdam in 1909, the daughter of a Belgian (a Walloon or French-speaking person) mother and a Dutch father. In her teens, she held a job with CAPI, a photo/optical firm owned by C.A.P. Ivens, who was the father of Joris Ivens. Joris, the head of the technical department of that company, began making experimental films in 1927.

While he was abroad filming his early influential experimental documentaries The Bridge (1928) and Rain (1929), van Dongen took over many of his duties at CAPI. She became deeply involved in his work, and with him helped to found the Dutch Film League. (Such cine clubs, created in reaction to what was viewed as the oppressive monopoly of Hollywood after World War I, were extremely important as the building blocks of European cinema in the 1920s and 1930s.).

Her first screen credit came in 1931 with Ivens’ Phillips Radio, although she worked uncredited on some of his earlier projects. A romance between the two developed. Van Dongen learned the new Western Electric sound system in Paris, then worked at the famous UFA studios in Berlin, doing both sound and picture editing, studying the RCA sound system. She then lived in Moscow, where she studied with Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov and Vsevolod Pudovkin, and lectured on editing. She moved to New York in 1936 with Ivens, after spending some months in Hollywood observing the technology and techniques of feature filmmaking. Spain in Flames (1936), narrated by John Dos Passos, was a compilation film she produced and edited. In 1937, she edited Ivens’ seminal film on the Spanish Civil War, The Spanish Earth, written and narrated by Ernest Hemingway. For the 1939 New York World’s Fair, she directed an experimental Technicolor film with stop-motion puppets. During World War II, she worked on films for both the Army Signal Corps and the Office of War Information. Other notable contributions were the editing of Ivens’ The 400 Million (1938), about the Japanese invasion of China, and their last project together, Power and the Land (1941). Two remarkable collaborations with Robert Flaherty, “the father of the documentary,” resulted in The Land (1942) and Louisiana Story (1948).

That Helen van Dongen is almost unknown today––even among editors––reflects a still operative deep tri-fold bias.

A year after van Dongen married Ivens, an avowed Marxist, in 1944, he left the US––without a return visa––for Australia with Marion Michelle, who became his camera woman and new love. Historian Richard Griffith called the Ivens/van Dongen work “a collaboration which has been one of the most fruitful in film history, but which has tended to obscure van Dongen’s own quite distinct talent.” The next and last time van Dongen and Ivens met was in 1978.

In 1950, van Dongen made her last film, Of Human Rights, which she produced, directed and edited. Following this 20 plus-year career, she married journalist Kenneth Durant, moved to Vermont and retired from filmmaking. Her writings about editing and her work with Ivens and Flaherty have been published, most notably in the Museum of Modern Art’s 1998 volume Making Robert Flaherty’s ‘Louisiana Story.’

Van Dongen worked in one of the most exciting periods for documentary with some of the most remarkable men who ever made non-fiction films. Her editing––which could invoke Soviet montage, the languidness of an Impressionist painting or the raw power of a dramatic battle scene––was styled to fit tone and content, not to impose a preconception upon it. She helped to define what was the highest quality of documentary being made: 35 mm (edited, of course, on an upright) black-and-white, non-sync sound, with extensive post-production work in music, narration and sound effects.

One of the best examples of her work widely available on DVD today is Louisiana Story. This last film by Flaherty, shot by the young Ricky Leacock, tells the story of an oil rig moving into a quiet Louisiana bayou. It has all of the elements that made Flaherty justifiably famous––including unbelievably gorgeous black-and-white cinematography. Flaherty’s method required that the story be “found” on location, through shooting and reshooting and shooting again, and yet again over many months. The crew, with Bob and Frances Flaherty, lived together for these months, screened rushes together, discussed and argued together, and listened to Flaherty hold forth.

Helen Van Dongen was masterful in many aspects of film- making. She was admired as much for her innovations in sound editing and design as she was for picture edit ing.

The finished picture is collaboration, Robert Flaherty’s vision realized by the long, hard work of a small, dedicated crew. When the film moved to the scoring stage, it was largely van Dongen who completed the work. She supervised the music with its composer Virgil Thompson, and Louisiana Story won the only Pulitzer Prize ever given for music. She also was responsible for the highly effective layered sound. Her detailed recollections of the making of this film provide special insight to both Flaherty and to editing, although Leacock has taken great pains to dispute her reminiscences.

That van Dongen is almost unknown today––even among editors––reflects a still operative deep tri-fold bias. First, she loved documentary film for both its social and its artistic possibilities; second, she was a sound and picture editor, deeply responsible for the finished product, but not viewed as its creator; and third, she was a woman. There were virtually no others in the field. And she was a strong, attractive, urbane, intelligent woman who could argue her point of view in any number of languages. One must suppose that she also loved brilliant and creative men, and even this––perhaps especially this––can be a great hindrance when a woman is trying to make her own voice heard on film.