By Rob Feld

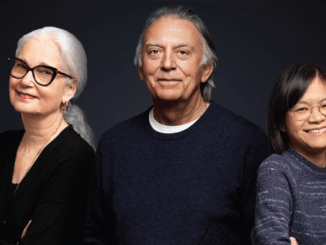

New York-based Sound Lounge was founded in 1998 by sound mixers. It has remained a specialty shop, expanding from its early commercial audio focus to include film, television, digital campaigns, gaming, and emerging media. The company has grown to occupy a significant space in the New York post-production landscape. Its team — including supervising sound editor Steve “Major” Giammaria, ADR Mixer Pat Christensen, and dialogue editor Evan Benjamin — recently won an MPSE award in Outstanding Achievement in Sound Editing (Broadcast Short Form) for its work on FX series “The Bear.”

The series leans hard into the rock ’n’ roll, dish-clanging world of a family-owned Chicago sandwich shop kitchen with some impressive sonic assaults. The sound-out-front vision for the series, which includes the nominated episode seven that was filmed as a single unbroken shot, provided a string of challenges for the team. They credit their company’s artistic focus for enabling a lot of their success, as well as the fact that so many employees enter the company at the dawn of their careers, work their way up through various departments to learn capabilities and find their own passions, and then stay after getting promoted from within.

Recently, developing technologies have decreased the need for clients to come in to work in their Manhattan studios—a process only accelerated by remote work during the COVID pandemic.

CineMontage: You’re in a highly competitive market with growing technologies that leave clients less constrained by geographical proximity, yet you have grown while staying niche and independent.

Steve “Major” Giammaria: I think there’s value in being strictly audio-focused. It is nice to be able to offer producers a package deal with finishing, picture, dailies, VFX, etc. But we do one thing, we do sound. In my career here, I’ve come onto a lot of shows starting on Season Two and I think that’s because the producers got stuck with somebody on a package deal that they wound up being unhappy with. So, then they come around and decide to find the right fit.

CineMontage: Do you find more opportunity or competition with clients’ ability to work remotely? Or do you think it’s a wash?

Giammaria: I think the convenience of it is nice, but I think it’s kind of a wash. You have the ability for people to attend sessions virtually who normally couldn’t because they’re somewhere else. But then you also have a lot more people “in” the session who maybe shouldn’t be there. The flexibility that comes with that also means that nothing’s ever locked and nothing’s ever done, which is … fine. But I much prefer people in the room collaborating together. My least favorite workflow is posting a Quicktime for somebody to watch later and send notes. The middle ground of a ClearView or something more interactive is good. The problem is how are they listening to it? If we know ahead of time there’s going to be a remote review component, we try and get everybody the same headphones.

CineMontage: Which raises the question of how you mix knowing that the ultimate audience will be watching and listening on myriad devices.

Giammaria: I think according to the latest Netflix stats, 72 percent of people still watch streaming content in their living room.

Evan Benjamin: The clients I work with don’t seem to go anywhere else. I’m actually starting something with someone I used to work with who moved to L.A. 15 years ago. I figured that was that but all of a sudden, he reached out. I asked if he was going to come to New York for it and he’s still pondering it. Being in New York wasn’t even a fundamental decision for him, which I thought was interesting. In the past, the logistics of how we work together geographically would have been key.

Pat Christensen: In the broad picture, who was using Zoom four years ago? People would want to Skype in to ADR sessions so the audio never sounded good. But now, instead of being limited to 32 k [kilohertz], you’ve got 48 k and everything sounds pretty darn good. Then we’ll send my secondary monitor, which has the picture on it, out a broken out HDMI into a converter dongle that goes to USB, so the computer and Zoom see it as a camera. That way, it’s already encoded into a DV converted signal so it’s all smooth. The swipe that goes across the screen is all synced up. That way, people who aren’t in the studio all the time can still have a quality session, knowing what they’re getting when I deliver something to their editor.

CineMontage: In this context, what were the particular demands of “The Bear” and that unbroken shooting style of episode seven?

Giammaria: The showrunners, producers, and editors had a clear vision that I think was there … [on] the page, which is rare that … [they’re] thinking about sound. They were thinking about how they wanted the kitchen to sound, what place the sound of a kitchen has in the anxious, pressure cooker environment. Those tension-and-release moments were well crafted in the picture, edited, and temp’d out to us to build on. It was a rare gift because, often, sound is an afterthought. I didn’t mix the pilot but had to replace some music. They sent an AAF that had two songs in one of the scenes. I asked what it was—if they were choices—and they said, “No, no, no. Both of them at the same time! They’re both playing, they’re fighting each other.” It was a whole other thing they were doing, and I loved it. Benjamin: I’m paraphrasing, but the creator, Christopher Storer, said, “I want this to be so abrasive that people want to turn it off.”

Giammaria: It was something like that. I was a bit put off by that at first but then I got what he was saying. I think we all knew we had something special in our hands. We had to mix in our character’s head and outside of his head. There were times when we were fully in his perspective, and then maybe his altered perspective, depending on if we wanted to question reality, which was fun to play with. I approached it mix-wise. I keep the dynamic range of television in a little bit of a tighter box than maybe some people would think to. I set my monitors a little lower at 76 dB rather than 79 dB to restrain the louder parts. I think if you had all these people screaming in a kitchen and you really let it roll, then go out to the alleyway where it’s really quiet, leading to these giant swings in dynamic range, it could have made the show harder to watch. When they start turning the subtitles on, we all have failed. I really tried to think of someone in a living room listening at a nominal volume, being able to enjoy the show while still feeling the changes in volume and intensity. So, when I’m trying to convey a change in loudness, actual volume is the last thing I reach for.

The number one complaint I get when I tell people what I do for a living is, “Why is it whisper, whisper, and then explosion.” It may sound amazing on the dubstage, but we have to be a little conscious of home experience.

Christensen: We have to fight everybody’s television processing and the loudness compensation that they all come with.

Giammaria: Who are we to tell you how to set your TV?

CineMontage: Ideally, though, how would you like people to set their TVs?

Benjamin: I do think that the dynamic … [range compression feature] should be off because … [it] really does screw with the mixes. It’s not even a gentle compression. It’s pretty harsh. I’ve been in people’s houses where I’ve turned that off. I just don’t think anybody would want a dumb machine with a clumsy limiter changing what Major or I did. We want it to be what we sent out at the very least, and then they should listen to it at a relatively good level because there’s a lot of nuance in there.

CineMontage: It’s sensitive work. Do you find the company’s structure and its artist-ownership aid your collaboration?

Christensen: I think it allows us to breathe a little easier. We don’t have as many bosses so you feel a bit freer as an artist without letting down our professionalism. So, we learned from a lot of top people, honed our crafts, and we don’t get poached by these giant conglomerates. I do think that makes us special because I think it helps the team.