By Peter Tonguette

From Francois Truffaut to George Lucas to Paul Thomas Anderson, moviemakers have always plumbed their own lives for source material. Among the latest major writer-directors to do so is James Gray, whose youth in the Flushing neighborhood of Queens, New York, during the 1980s provided a particularly rich starting point for his latest film, “Armageddon Time.”

One of last year’s most talked-about new dramas, Focus Features’ “Armageddon Time” stars Banks Repeta as Paul Graff, the youngest member of a Jewish family in Queens in the early ’80s. Paul’s parents, Irving (Jeremy Strong) and Esther (Anne Hathaway), agonize over the future of their daydreaming, artistically inclined son. Ultimately, Irving and Esther pluck Paul from public school — thus disrupting his friendship with Johnny Davis (Jaylin Webb), a Black student who shares Paul’s imaginative, big-dreaming nature — and enroll him in a private school, a decision that plays out disastrously. Looming over the story is Paul’s grandfather, Aaron (Anthony Hopkins), who attempts to offer guidance to his grandson amid a world rife with prejudices and injustices.

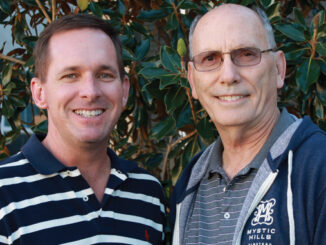

Of course, even an autobiographical film requires collaborators, and Gray assembled a top-flight crew to help his memories come alive, including his usual cinematographer Darius Khondji, ASC. Their ranks also include picture editor Scott Morris, who entered Gray’s orbit as a first assistant editor on the director’s “The Lost City of Z” (2016) and an additional editor on “Ad Astra” (2019), both edited by John Axelrad, ACE, and Lee Haugen.

In cutting “Armageddon Time,” Morris called upon aspects of his own background: He grew up on Long Island and felt connected with the setting of the new film. “I’m not from Flushing, but . . . I have family and friends in Flushing,” said Morris, who entered Emerson College in Boston intending to become a cinematographer before falling in love with editing. “My brother lives in Queens, not too far from the school in the film, so I have a lot of connection with that.”

Perhaps even more important, Morris had developed a feel for Gray’s style and working methods from their previous films. “His films are so personal,” Morris said, “so you can imagine the cutting room is a very personal, a very safe space.” And that’s just the sort of space required to tell a story as revealing and delicate as “Armageddon Time.”

CineMontage recently spoke with the editor and the director.

CineMontage: Scott, how did you first come to work with James Gray?

Scott Morris: I first came out to LA to work in film. I got a job with Lee Haugen, who was an editor on a TV show. We met and became very close. He was the apprentice on [Gray’s] “Two Lovers” [2008], and then, when “The Lost City of Z” came around, John Axelrad had a scheduling [conflict]. Lee was hired to come in and start the editorial process; he was co-editor with John. I had been working with Lee for a little while already, and that’s when I got the call to go to Ireland.

I read the script on a plane going to Belfast. One of the best script-reading experiences of my entire life. It was just a wild adventure, and I met James in the geographical society building in Belfast. They were shooting the briefing scene, and I met James on set. The very first thing he said to us was: “Come here, come here.” He brings us to his laptop and he had music he was playing back or sound design for the film. . . . He didn’t know me at all — we were strangers — and he just immediately brought me into the creative fold.

[On “The Lost City of Z”], there was a lot of material, so we all just got really close really fast, spending very long hours together in New York, eating really good food, and working hard. Lee and John were mentoring me at this point. We went and did a film, a remake of “Papillon,” in between projects just to keep the team together. I’d done more cutting. Then “Ad Astra” came along. I started as a first assistant on the show, and as the process went along, I got upgraded to an editor.

CineMontage: James, what did you see in Scott to begin what has become a multi-film relationship?

James Gray: He is a very intelligent person. He is very aware of what it is that matters in a movie — at least to my taste, which is an emotional directness and honesty — and to keep his eye on what matters. Is the actor being honest? Is the scene making sense in the framework of what it is you’re trying to express? You recognize that in people very quickly, and I saw it in him.

CineMontage: Scott, how did you make the jump to solo editor on “Armageddon Time”?

Morris: John [Axelrad] is a mentor, and he told James, “He’s more than ready to do this.” And James was excited — because we were already so close at the time — to do it. He called me one night, and he said, “I’d love for you to do my next picture.” I said, “Of course. I’m available.” He sent me the script. And I knew about the project. It was shocking to me how much I related with a lot of elements, because I had some similarities in my childhood growing up in New York.

Gray: I always like to give people a helping hand if they need a job, and he deserves to be editing movies.

CineMontage: How do you both work together?

Morris: I was there cutting while they were shooting. They’d shoot, and I would screen. I’m religious about screening. It’s a very personal experience for me. The way I see it, you experience the film, as an editor, really three times: You experience it the first time only when you read the script; the second time is when you screen the dailies, the only time you’ll ever experience that footage in a raw, visceral way, the way an audience member would; and the third time when you watch that first assembly, the first screening of the feature. That’s it: you get three opportunities. I take them all very seriously.

Gray: To me, the editing process is drilling down on the best possible narrative idea. Sometimes you have to fight the footage; sometimes you don’t. Sometimes it’s about maximizing the footage. But it’s not about adhering to your original concepts. That will get you in a pickle. In other words, you have to start thinking that the film starts speaking to you. You can’t sit there and say, “This is what I had, this was my original idea, and we’re going to try to force this to work.” That is folly. It becomes its own thing once you’re in the editing room.

Morris: I’m a very analytical person. I think most editors are, instinctually. So I try to turn off my brain completely and absorb the material, get it in me, and then when I work, it’s my body. It’s almost like a dance. My body’s working. And then, after I assemble it, then I’ll watch it and then my analytical brain turns on and I go, “Oh, okay. Interesting.” Because I want my subconscious to do the work for me.

Gray: It’s not about being open. “Open” is the wrong word; “open” is a word used, I think, to describe people who don’t have an idea. You have to have an idea. But what you have to be is willing to listen and to respond to things that are bigger than what you thought about.

CineMontage: Scott, what was it like working with the young cast?

Morris: I knew James would get an incredible performance out of whoever he cast. I just knew he could pull it off, I was never concerned. And then, of course, we get the footage back and immediately it’s incredible. The kids are just phenomenal. It was never an issue of having to tailor a performance or create a performance or cut around a performance, ever. Banks and Jaylin were just rock-solid.

Throughout the editing, one of our mottos was: “How do we get more into the lead character’s head?” We’re always looking at the way we can cut a scene where we’re constantly cutting back to Paul, or starting the scene on him, or ending the scene on him. CineMontage: One of the most bravura scenes in the film is a chaotic family dinner with multiple family members talking, bickering, arguing, and Paul protesting being served spaghetti and finagling a way to order dumplings. How did you construct a scene with so much to balance and so many awkward, painful, relatable moments?

Morris: That was one of the most fun scenes to edit. I have a pretty funny story around it. I screened the dailies on a Friday. My brother has two young nieces — very young children. We had dinner at a restaurant. And it was on a Sunday night, and I cut the scene Monday. And it was just pure chaos [at the dinner]: I was living the dailies in my real life. It was in my head fresh, and I’m watching the kids running around the table and messing up orders and the water falls over. . . . I come in the next day and I cut the scene with all of that fresh. It couldn’t have been more serendipitous — all of that energy fresh in my head.

James is incredible. He’s got his master, and on his master he would do the whole scene. He let [the actors] go for six minutes of improv before they got into the scripted lines. That’s all covered in particularly the masters, but in all the coverage, as well. We would have an incredible amount of improv and just a plethora of dailies. . . . I’m just looking for anything that excites me, whether I find it funny or emotionally interesting or there’s a look here that I think could be really interesting. I’m just looking through that and building these selects. Then I break the selects into sequences based on character. . . . I want to build the scene based on selects.

CineMontage: There are several scenes presented largely in long, uninterrupted takes. One of the best is when Paul and his father are sitting together in a car following [spoiler alert] Aaron’s funeral.

Morris: The funeral, and the scene with the father, it was about the silence, the unspoken. So much goes unspoken there, and in real life oftentimes almost nothing goes spoken in moments like that at a funeral. . . . This is the case in I think a lot of James’ films: it’s about the space in between the words. It’s about what’s happening in the space, and creating that space in the editing. If you have shot/reverse shot and he’s cutting back and back and back, it loses all of its weight and its drama.

Gray: I’ve made car chases and space chases and all this, and those are much easier to edit than that car scene between his father and him at the end. That took us days. The nuances matter, and the dialogue matters, and the pauses matter. All of that stuff is important: what to remove, what to keep.

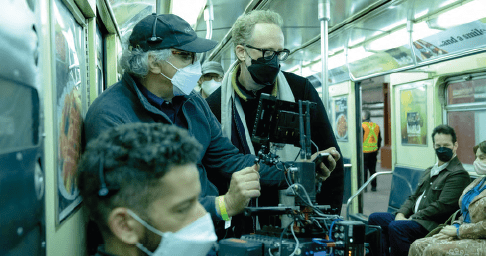

CineMontage: James, is this your first time shooting digitally?

Gray: I still love 35mm film, but it’s very expensive now. I would even eat the expense, but in order to achieve the look of like a 1980 movie, the stocks don’t look like that anymore. . . . In order to get it to look old, you have to do so much: you have to underexpose it two stops, push it two stops — you really have to beat it up. . . . I don’t think the Alexa is as good as film, but I think the Alexa 65, which is what we used, has started to get quite close.

‘Sometimes you have to fight the footage; sometimes you don’t.’

Morris: It was the first time getting a twenty-minute James Gray take. He’s always done film. . . . In this case, I think we had a couple of takes on Jeremy that were 20 minutes long. The way I screen dailies, I’m really intense, so I live in it. If it’s a 20-minute take, I drink some water, I’m fully engaged for 20 minutes. I don’t break, I don’t look away.

Gray: I don’t remember doing a lot of 20-minute things, or not calling cut. It’s possible — maybe the dinner scene. But I had that tendency in film, too. I remember one night, on “We Own the Night” [2007], we shot 27,000 feet of film.

CineMontage: There’s another scene with minimal, well-chosen cutting later in the film: When Paul sees a guidance counselor-like figure at his new private school, you stay on the push-in to Paul rather than cutting back to the guidance counselor.

Morris: That scene was actually shot with coverage, and right away, it was pretty clear that it wasn’t going to be cut with coverage. I don’t know if James mentioned anything, but it was definitely clear that there was no way we were going to cut away from that.

Gray: I had a very good take on the teacher, but what you’re seeing in the movie is take one of the kid. He was great, and the movie is about him and about what he’s going through in ways that he can and cannot understand fully. I felt there was absolutely no reason to cut away from him. Sometimes good editing is knowing when not to cut.

Morris: That was one of the scenes where [Gray] did a lot of takes. Usually, he doesn’t do that many takes. Every once in a while he will, especially on some of these longer things that we could hold on. But I think he did — I’m making up a number — maybe 15 takes or something [for this scene], and it was the first take that we used on Paul for that push-in.

Gray: It’s like Ringo Starr is the greatest drummer because he knew when not to play. He wasn’t just playing a bunch of notes that gummed up the song. He was playing always exactly what the song needed, and that’s the hardest thing ever. There is no incorrect drumming on any Beatles track, and what that tells you is the guy had the greatest taste ever and knew, sometimes, you didn’t play. Sometimes we don’t cut.