By Sharidan Sotelo

March 13, 2020 — The date to remain on my cutting room wall in Glendale.

Shutdown. The shift for all of us.

This was strike three for me — three shows in a row shut down unexpectedly. Two pre-pandemic and now this. Wouldn’t you know it?

After the shooting stopped on show number three, “Mr. Corman,” a comedy about the life of a teacher in the San Fernando Valley, I worked from home in a hastily rearranged living room for two weeks. Joseph Gordon-Levitt and I edited the “COVID Cut” of the pilot episode and put the show on the shelf.

Then the AVID collected dust. Walks. No traffic. Zoom birthday. Indoor dancing. Sanitizing. Budgeting. Rioting. Protesting. Crying. Meditating. Creating. Planning.

As the prospect loomed of a loss of career and income, unbeknownst to me, the pandemic would fate me with two missions divergent yet necessary to my survival.

The first mission was a COVID-19 memorial — “Save my DATE / Names Not Numbers” — that I created in the middle of the Los Angeles curfew. The concept is loved ones handwrite their expressions of grief to those they lost—what they would have said as the victim took their final breath. The long-term plan is to build a tangible memorial to honor the dead.

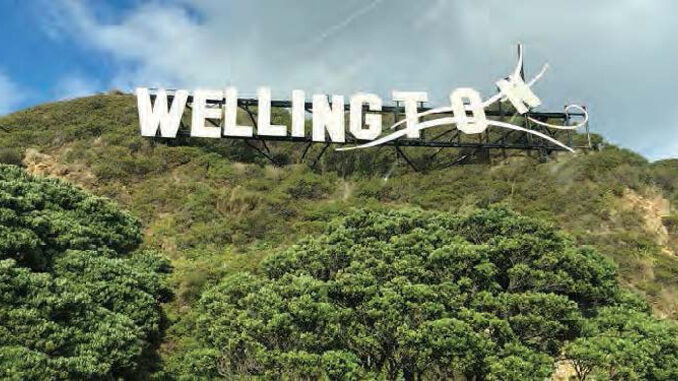

The second mission would come in the form of a gift, not only of income but of sanity — a job in a faraway land and living a day in the future, New Zealand. The last time I was in the Southern Hemisphere on location was for “Red Planet” in Australia during Y2K. It seems it would take a worldwide crisis to bring me back to that side of the world.

When Joseph Gordon-Levitt asked me to come back to my shutdown show, “Mr. Corman,” to be reborn on location in New Zealand, I didn’t believe it at first. I put the opportunity in the back of my head as a remote possibility, but as with everything in this business, until you’re on a show, you’re not on a show. At the time of Joe’s proposal, New Zealand had a small outbreak and the borders were closed for a couple of weeks. There was a question as to whether the virus and the country’s regulations would allow our show to happen.

Call from my agent. Emails. Visa. Time to pack and get my American life in order to be on hold for seven months. I filled my suitcases in a hurry. Said my masked socially distant goodbyes. Donned a face shield and my production-provided K-95 mask and I was off like an astronaut for passage into another land, braving the always-possible COVID-19 exposure.

LAX. Ghost town. The traffic void. I had never seen the international terminal so deserted. I checked into my adventure and my next mission. Capturing the moment with a selfie post, the hashtag #TalesOfPandemicTravel was born. I had apprehension and tremendous survivor’s guilt as I hit the post button on my phone — a feeling I termed USAPTSD — but to my surprise, the post was met with a flurry of positive response. So I forged ahead, boarding the plane, reluctantly taking off my mask to eat, grateful for the business class pod which left me feeling a little safer being able to cocoon away from COVID.

Upon landing, one more mask removal at immigration in freaking New Zealand! I was whisked away to an undisclosed location for managed isolation. My bus ride ended up at the Grand Mercure in Auckland. During a military check-in two meters apart from my fellow passengers, I was assigned a border detention number, hotel room 918, my dystopian-novel I.D., a bag of required fresh paper masks and a menu for seven days of room-service choices. Then into the lobby, where the courteous hotel staff brought my bags up for my 14-day detention.

The brilliance of utilizing hotels for managed isolation is not lost on me. The location turned a mandatory existence into the blank canvas of a hotel room. You can “paint” a hotel room to be whatever you want it to be. I decided to treat it like a spa retreat, a place to recover from “USA PTSD.” Room service. Laundry Services. Health checkups each morning (not only body temperature but mental health check, as well). Hotel WiFi. Television. Fishbowl view of the COVID-free, mask-free, lucky inhabitants of Auckland. I retained my lockdown coping habits of meditation and journal writing to complete the rehab environs.

But the dystopia was still present. A communique slipped under the door informed us of a COVID case amongst my fellow inmates and stated that we were to remain in our rooms until the positive person could be transferred to a quarantine facility. We were allowed an hour of outside exercise every other day behind two rows of fencing on Queens Wharf. The COVID-free could watch us in our people-zoo-prison as we walked our laps of contained circles.

From my room, I watched the Dodgers win the World Series and saw the other international sport, the U.S. Election returns. I felt like I was still in my home time zone as I waited on the border (the airport and managed isolation are considered New Zealand’s border) for a negative result on my Day 11 COVID-19 test and release on Day 14 for good behavior.

I ventured from the Grand Mercure and masked up for the flight to Wellington and my first Kiwi home, at the Hotel Bristol, and for my reentry into a life without a pandemic. My New Zealand assistant, Amanda Mulderry, greeted me with a hug. It was so strange to have a sensory exchange with another human being as I had COVID-habitated in the States with only my furry canine companion, Puppicasso.

Amanda and her family immediately made me feel welcome and introduced me to the COVID Tracer App. Barcodes are on every establishment in New Zealand (including outdoor special events) are to be scanned, and the app keeps a 30-day diary of the places you went, which is a practical tool for keeping the virus at bay. If the app notifies you that you might have been exposed, get a COVID-19 test and isolate until you get results. It’s simple and effective, if everyone participates. There is a strong sense of community in New Zealand. It is common for Kiwis to address a group as “Team.” Whānau (the Maori word for family) is highly regarded here. As New Zealand is a small country on an isolated island, there is the profound sense that everybody and the surrounding environment is interconnected.

The production had a Powhiri for the few Americans on the crew. It is a traditional Maori welcoming ceremony complete with a Haka (a vigorous Maori group dance) and a Hongi, which is a greeting where you touch noses and sometimes also foreheads. This was a pretty overwhelming sensory overload: crowds and close contact just two days out of managed isolation. It was here where I met Joseph Gordon-Levitt for the first time face-to-face; until then, he had been a face on a screen. And now, a year after a video conferencing interview, he was three-dimensional. So with this welcoming ceremony, and the news of Biden being declared the winner of the American election, I began my working location life.

Appropriately enough, production was located at Avalon Studios. The mythical Avalon island has always resonated for me as a place where a person heals from their wounds, as King Arthur did.

The production started in Level 2, which meant being masked when we were outside of our bubbles. Everyday, regardless of what level we were in, we were required to scan in with our tracer app, receive a temperature and health status check, get a sticker for the day and then we were set to work. After the first week, we were back at Level 1; the masks came off and we were free to mix with the other bubbles.

The greatest culture shock for me on the other side of the world was driving on the wrong side of the road. I was grateful to have Amanda drive with me for the first time. Afterwards, I have to admit, with the extreme wind of Wellington, I was white-knuckling it to work every day. The commute filled me with a certain dread. Jonno Woodford-Robinson, my fellow editor, and the other assistants, Greg Jennings and Jessica O’Donoghue, schooled me in their ways of coffee-making, pronunciations, places to visit/eat, and Kiwi television shows. The crew’s input guided me into the further exploration of the country.

New Zealand editorial is different from America in that they are working for Team New Zealand. There’s a sense of national pride in the editing room. I have never been in a cutting room in the States where the quality of work was performed in the name of the U.S.A. — another example of the camaraderie of the Kiwi people.

The crews and facilities in New Zealand are top notch, and the film industry attracts migrant professionals from all around the world. Sometimes, I was hard-pressed to find native Kiwis. Amanda became a citizen of New Zealand from her birthplace of Ireland, a proud life event to have happen during my stay.

Since I couldn’t go home for the holidays and was on my own, I expanded the extent of my #TalesOfPandemicTravel from my morning walks in Lyall Bay, where I lived, to the earthquake ruins of Christchurch, the glaciers of the South Island, Hobbiton, and the volcanic activity of Rotorua. But it was in Queenstown that I participated in a single activity that blew the USAPTSD of 2020 out of me… I catapulted across the Nevis River! The catapult is a human slingshot that sits 300 meters above the river floor. I chose this thrill adventure over bungee jumping because I didn’t want to have to jump off the platform myself, I figured it would be easier if someone else did the launching.

It wasn’t easier. The accumulation of nerves as I was being harnessed in was so immense that it would take being flung 150 meters across the valley with 3Gs of force at about 100 KPH in 1.5 seconds to blast all of the anxiety about the pandemic — and culture shock — out of my system. As I dangled on a string and focused my gaze on the river floor below, all of the nerves disappeared. The pandemic was and remains an invisible threat, but the catapult, being purely physical and visceral, was exactly what this astronaut needed to leave 2020 behind but not forgotten.

Spending New Year’s Eve in Auckland with a close-together crowd and fireworks off the Sky Tower, I thought about all the people back home who were living vicariously through my posts. And for the first time, I finally started to feel no guilt for this opportunity to live and work in New Zealand.

Looking at our tight schedule, I don’t see a scenario where editing could have worked remotely. Joe is such a hands-on and collaborative artist, the episodes really thrived and took their shape with the intangible creativity that can only exist when people collaborate in person in a cutting room. I know that my colleagues reading this have a leg up with remote editing and all the ease and frustrations that Work from Home affords: no commutes, fewer internet problems, separation of life and work, Zoom overload, and other facets I will know soon enough. But I think my unique Kiwi experience will prepare me for our re-entry into society when there is a return to in-person editing rooms. Contact and energy between people is something to be savored, and New Zealand shows how the pandemic can be dealt with if we all do our part and work together.

At my farewell lunch, I was gifted a Pounanu Toki (greenstone necklace) from Pamela Harvey-White, the producer. The Toki, or Adze, signifies strength, control, and personal growth, which I carry with me today.

I equate my time in New Zealand with their national mascot, the Kiwi bird — fragile and endangered, unable to fly, but magical in concentration. I am forever grateful for the experience, and I hope that sharing the beauty of the land and the people in #TalesOfPandemicTravel can give people a glimpse into a life returned.

Kia Ora, New Zealand.

To see more New Zealand photographs go to Instagram @Puppicasso. “Mr. Corman” streams on Apple TV+.