By Peter Tonguette

In the world of international motorsports, the glamorous drivers, glitzy sponsors, and incredible racecars draw most of the attention, but any real auto racing fan knows that it’s the pit crew that does the heavy lifting.

The pit crew ushers the racecar into place to refuel, to detach and discard worn tires, to affix new tires, and to send the momentarily sidelined racer back to the course in good shape. If the pit crew has done its job, no one will have noticed their expeditious handiwork.

Something of the same spirit of committed professionalism and grace under pressure characterizes the post-production team on Michael Mann’s “Ferrari,” released to theaters late last year. The Neon release stars Adam Driver as Enzo Ferrari, the stylish, sophisticated automotive pioneer who, as the film opens, finds his attention split between his racecar empire and his muddled personal life: He is bereft over the loss of his son with his wife, Laura (Penelope Cruz), while also maintaining a relationship with his mistress, Lina (Shailene Woodley), with whom he also has a child. This is a personal psychodrama set amid the world of high-octane racing.

For Mann, the film is the fulfilment of a long-stated wish to make a cinematic portrait of Ferrari in full: his life, his loves, and his cars. The filmmaker demanded the sort of authenticity for which he had become famous on such earlier triumphs as “Heat” (1995), “The Insider” (1999), and “Ali” (2001). On this film, engine sounds had to be authentic to the cars being depicted on-camera, and the Italian-inflected English dialogue had to sound realistic but intelligible. All of this, and more, had to be achieved on a schedule far more compressed, and a budget considerably more limited, than the filmmaker’s large-scale studio pictures.

Consequently, Mann assembled a team of post-production pros. Many had worked with Mann in the past — some for decades, others for a shorter period — along with those who were new initiates. Together, they took charge of “Ferrari” in post-production in much the same way that the pit crew is responsible for a car mid-race: they refueled the film, changed its tires, and assured that, when it prepared to make its rounds on the course of the year’s best pictures, it was in tip-top shape.

CineMontage recently spoke with some key members of this “pit crew”: picture editor Pietro Scalia, ACE; supervising sound editor and re-recording mixer Tony Lamberti; supervising sound editor Bernard Weiser; re-recording mixer Andy Nelson; music editor Paul Apelgren; and production sound mixer Lee Orloff.

CineMontage: Pietro, “Ferrari” is your first film with Michael Mann. What interested you about the project?

Pietro Scalia: I’ve known Michael for many years, and over the many years he’s been trying to put this movie together, he would contact me. I was very flattered by that. I knew of the project and the long gestation of it. Having the opportunity to work with a master, and somebody that I admired for so long, I’m happy that finally it was ready to go. I loved the script, and I had seen the evolution. I was amazed how he was able to crystallize this story so beautifully.

CineMontage: How did you work together in putting the picture together?

Scalia: One of the things we had to adapt very early on is the communication in the form of notes from Michael. Before he would shoot, he would share all his research and notes. During the shoot, he would note things that he liked, but when we were in Modena [Italy], it was a very tight schedule. He would come in on weekends, but he didn’t have much time to review the material. He said, “Just go ahead and follow the notes. We’ll review it on the weekends.” That gave me the kind of initial freedom to tackle the scenes, having all the information that I needed. Then we would review them on the weekends and, to my surprise, he liked these scenes, which gave me confidence.

The real editing part of it with Michael was after the shoot in Italy, when he returned to L.A. He literally went back to all the dailies, he commented on them, he recorded his reactions — very, very specific. His assistants would transcribe them, and we would get these notes. We created this giant library of notes. That’s his process. He has everything catalogued and noted.

CineMontage: Are Mann’s notes about his favorite takes or moments he likes?

Scalia: Exactly that, but also very, very specific. For example, in going through the takes, he noted his preferred takes, but then also the specific sections where he would stop the dailies and give you specific timecodes.

He would revisit older cuts, view them again, and sometimes make combinations. It was a continuous fine-tune to remove everything that’s in excess. How does this compare to that one? Sometimes we’d have three or four different cuts of the same scene at the same time. There are sequences that I cut 50 times.

CineMontage: Tony, you first worked with Michael on “Blackhat” (2015), and you learned about “Ferrari” while working on a director’s cut of the earlier film.

Tony Lamberti: He had this alternate edit of “Blackhat” that he showed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, and on those weekends when I went in to work on it, he had all the materials out for “Ferrari.” His offices were filled with these giant poster boards of locations. He had build-sheets for the cars.

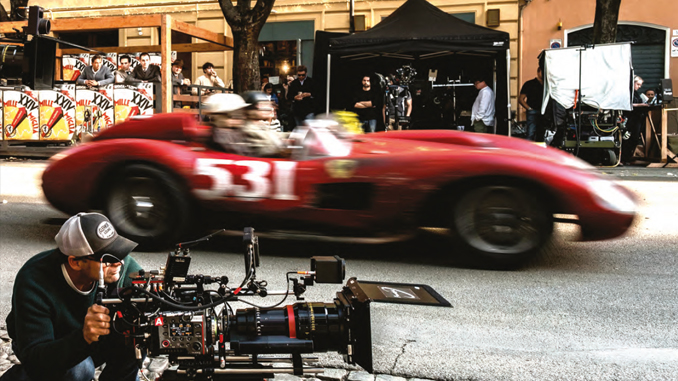

All the cars that are moving on-screen are actually replicas of the real cars. He had to build them from scratch in order to be able to mount cameras to them and put them through the rigors of production. The real cars are worth tens of millions of dollars. I’ve never worked with a director who just goes so deep into every single detail.

CineMontage: That meant you had to record the sounds of the real cars — not the replicas seen on-camera, but the actual cars they represent, right?

Lamberti: Specifically, the engines. The cars that were the replicas had little four-cylinder turbo engines in them, so we could run them all day long and beat them up, but the sound was not the real sound. The way that Michael’s attention to detail plays out is: “We’ve got to have the authentic sounds,” so that when a real racing driver watches this movie, they’ll be transported back. We started chasing down cars, and we had many, many avenues we were chasing down. The big challenge for me was: “How do you convince collectors and museums to allow you to record their highly valued cars”?

CineMontage: Once you managed to line up the real cars, how did you mic them?

Lamberti: So now we had all the cars wrangled. I had a shot list of everything that needed to get shot, and then the cutting room sent clips of the racing scenes so they could actually see on-screen what action needed to be shot. We had all the pieces in place. And then it’s just taking out the driver and performing those things. We were very, very specific: “We need starts, idles, aways.” All of these things needed to be done at at least 5,000 RPMs and above. We had all these stipulations; we need to have these cars revving their highest revs and doing these different actions. Then it was up to the guys to go out in the field and record it.

Michael has done enough amateur racing to really know what’s going on, and he’s been a Ferrari guy forever. Not only did we have to get the sound of the engines right, but we had to get the performances right, and what we liked to call racecraft. So all of those downshifts, all of the upshifts, all of the accelerations and decelerations — they all had to be absolutely spot-on to not only what we were seeing on-camera but when we’re not seeing things on-camera.

CineMontage: Lee, the recording of the dialogue scenes came under your purview.

Lee Orloff: It’s always about authenticity with Michael. As far back as anything I’ve ever done with him, he doesn’t build sets. If there’s a real location that we can go to, where the event takes place, we’ll be in Chicago for “Ali”; we’ll be down in Pascagoula, Mississippi, for “The Insider” in the courtroom. Once you realize that that’s his approach, you read the script and you know: “OK, so we’re going to be there.”

When it comes to racecraft, there’s no way that he’s going to allow anything on the soundtrack to be anything short of absolutely authentic. And this is stuff that’s sometimes barely in the picture, but it’s happening in the background. We’re having a conversation between Enzo and a driver on a racetrack, and the Maserati and the Ferraris are doing the time trials. He created that so that each one of those shifts, and everything in the track, supports that whole sense that you’re in the place. This is the way it would be if you were there.

CineMontage: Bernard, you had previously worked with Mann and with Tony on “Blackhat.” What was the setup like on “Ferrari”?

Bernard Weiser: Tony and I knew that, for Michael, having the two of us be supervisors was the way to go. We knew the demands that we were walking into. I’d say this show proved us correct with that view of it. Michael likes to have direct contact. As a result, I was the one that, when I started, was immediately embedded with the picture department, starting at the very end of January or beginning of February. My cutting room was right next to Pietro and right in the middle of it all. That way, Michael could walk from room to room and discuss what he was thinking.

Andy Nelson: My experience with Michael is that everything’s evolving. In other words, he doesn’t finish a cut, come to the stage, and start mixing the sound. He’s finishing the movie in all these areas at the same time. We’ll put up a sequence on the screen and we’ll work on it with him, but it’s informing him, as we’re doing something, of what he thinks he should do pictorially. It literally comes alive on the big screen at that moment in time. He’ll move the picture editing department over to the dub stage, right next to where I am, and he’ll be back and forward because the cut will change. You have to be ready to work in a very fluid style with him.

Weiser: The first thing Michael said to me the first day I was there was that his biggest concern was the understandability of the dialogue. This was a twofold problem: You had the Italian actors speaking English, many with a very heavy accent, and then you had the English-speaking actors trying to speak English but with an Italian accent. CineMontage: How did you

address the issue?