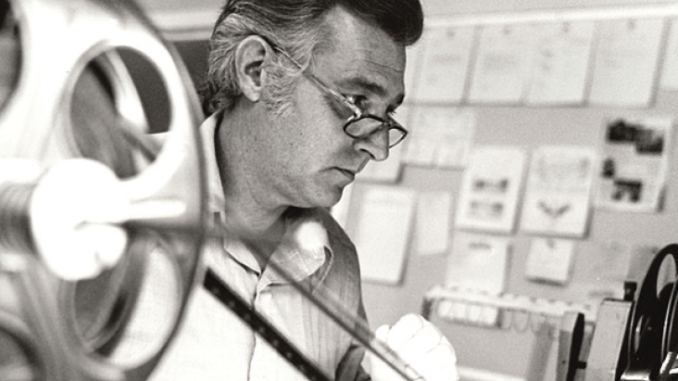

MARCH 5, 1934–OCTOBER 24, 2024

As a veteran of Old Hollywood and a pioneer of New Hollywood, picture editor John F. Burnett, ACE straddled two worlds. Burnett, who died Oct. 24 at age 90, rose through the ranks of the editorial department at Warner Bros. where he served as the assistant editor on many of the studio’s leading productions from the last decade of the Golden Age, including Billy Wilder’s “The Spirit of St. Louis” (1957), Mervyn LeRoy’s “Gypsy” (1962), and George Cukor’s “My Fair Lady” (1964).

Yet by the time the longtime studio employee earned the privilege to edit films himself in the late 1960s, the movie business had moved on. Large-scale musicals, star-driven vehicles, and Production Code-controlled scripts were on their way out, but the editor adapted with the times. Burnett edited several of the signature films of the adventuresome New Hollywood era, including Sydney Pollack’s “The Way We Were” (1973), Herbert Ross’s “The Goodbye Girl” (1977), and Norman Jewison’s “And Justice for All” (1979). Along the way, he helped bring several of his mentors from the old days into the new times: Burnett edited Blake Edwards’s meditative, melancholy Western “Wild Rovers” (1971), starring William Holden, Ryan O’Neal, and Karl Malden, and George Cukor’s final film, the superb romantic comedy-drama “Rich and Famous” (1981), starring Jacqueline Bisset and Candice Bergen.

No matter the genre or epoch, Burnett was a master of his craft.

“He was so fast,” said his son, camera operator, cinematographer, and producer John Earl Burnett. “He would be in first cut the day after they finished shooting. He would have his assistant make a black-and-white dupe of his first cut, and then after they finished, he would have it for reference to see what had changed. It was so funny—it would end up almost back where he had it.”

In his life outside of the cutting room, Burnett also contained multitudes: He was at once a trailblazing president of the Motion Picture Editors Guild (1975-76) and a modest, unassuming man who was as comfortable working on his 20-acre ranch in California as he was serving the industry where he had established his name.

No matter how Burnett is defined, however, his death represents the end of one of the most notable careers in postproduction.

“He would take what a director gave him—and Cukor gave him thousands and thousands of feet a day because he did everything from the top—and he just had this way of putting it together,” John Earl Burnett said.

One of two sons born to Gilbert and Clara Burnett in Kansas City, Missouri, John F. Burnett only briefly made his home in the Great Plains. Drawn by the promise of California, Gilbert and family pulled up stakes to Burbank and eventually became an engineer at the Lockheed Corporation. At John Burroughs High School in Burbank, John stood out as a track athlete and a light opera singer. “The problem was, that wasn’t fashionable at the time,” Burnett said of his vanquished musical ambitions in an interview with CineMontage in 2012. “I would have done much better if I was twangin’ with a guitar! The USO didn’t want to hear me sing ‘Figaro’ from ‘The Barber of Seville’!” During his youth, he nurtured a love for horses and roping that would stay with him all his life.

The Burnetts’ proximity to the movie business provided an alternate career path: With his family’s home located about two miles from Warner Bros., his mother suggested he seek employment there upon his graduation from high school. “Jack Warner didn’t have much of a formal education and wasn’t that fond of college graduates,” Burnett told CineMontage. “He wanted people to come through the ranks.” Burnett began as a messenger on the lot, and, following his service in the Army during the Korean War from 1952 to 1954, returned as an apprentice and then an assistant editor—the ranks of which had been depleted during the war when many assistants became editors. His first film as an assistant editor was “The Spirit of St. Louis,” edited by Arthur P. Schmidt.

The following decade, Burnett received an early opportunity courtesy of his later collaborator George Cukor. During the making of Cukor’s 1962 drama “The Chapman Report,” editor Robert L. Simpson, ACE declined the director’s request to work on weekends. “And so nobody was there but poor John!” Burnett recalled in an interview with CinemaEditor in 2008. “I didn’t have a lot of experience editing at that time, but I came in and worked with George. And he didn’t forget the loyalty of me coming in and working with him.”

Years later, after Burnett had become one of the most distinguished editors in the industry, Cukor called on him to edit his acclaimed television film “Love Among the Ruins” (1975), an historical romance starring Katharine Hepburn and Laurence Olivier. The two worked one last time on “Rich and Famous.”

“In a lot of companies, the department heads came to dailies. Not with George. George said, ‘This is my editor’s and my time,’” Burnett told CinemaEditor. “There was one thing that George was very strict on. George demanded that you stayed on the person talking until he or she finished their sentence. If the line was, ‘I think we ought to go to town right now,’ as soon as ‘now’ was over, you made your cut. If there was a little reaction on the other side, you would use it, and if not, the other person would then say, ‘No, let’s go in about two hours.’ A lot of people think that if you overlap the last part of that line over the incoming person’s face, it speeds up and smooths out the cut and the reaction and the tempo of the dialogue. A couple times, it worked better if I did that because of something technical. And every time George caught it, he said, ‘John, you know better.’”

Throughout his career, Burnett nurtured longtime relationships with directors and producers, including Blake Edwards, for whom he cut, uncredited, portions of “The Great Race” (1965), edited by Ralph E. Winters, ACE and later, once he had become an editor, “Wild Rovers” and “A Fine Mess” (1986), the latter with Robert Pergament. Burnett received his first official opportunity to edit thanks to director Robert Ellis Miller, who hired Burnett to cut his much-admired adaptation of Carson McCullers’s “The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter” (1968) and promptly signed him to a multi-picture contract (from which he was later released so he could work elsewhere).

Because of his love of horses and ranching, Burnett considered “Wild Rovers” to be among his favorite projects.

“He was a Western and cowboy kind of guy,” John Earl Burnett said. “It was just a good, fun shoot. Blake only did eight-hour days. We went fishing with Karl Malden. We went to the O.K. Corral with Tom Skerritt. [Edwards’s wife] Julie Andrews had ‘101 Dalmatians’ flown in. It was almost like a little family.”

Burnett also edited numerous films for producer Ray Stark, including “The Owl and the Pussycat” (1970) starring Barbra Streisand and George Segal, and “The Sunshine Boys” (1975) starring Walter Matthau and George Burns. And, after cutting his teeth on “Gypsy” and “My Fair Lady,” Burnett again found himself assembling musical numbers on a pair of New Hollywood spins on the genre, the box-office smash “Grease” (1978) and its sequel, “Grease 2” (1982).

Having reached the apex of his career, Burnett stood for and won the position of president of the Editors Guild, where his accomplishments included negotiating a new contract that led to a 50 percent compounded increase in wages over three-and-a-half years and the guarantee of single-card, up-front credits for picture editors, which was far from the norm at that time. “We want a card up-front to match the cameramen,” Burnett told CineMontage, recalling his conversation with MCA Universal’s Sid Sheinberg and Lew Wasserman amid the contract negotiations. “We don’t want to be in the technical credits.”

He served in various capacities with the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, including as Executive Secretary (1983-1984) and on the Board of Governors (1975-1985).

Burnett’s later credits are highlighted by his work on two gargantuan historical miniseries, “The Winds of War” (1983) and “War and Remembrance” (1988-89) both based on equally epic-scaled novels by Herman Wouk. With Peter Zinner, ACE, Burnett received an ACE Eddie and a Prime-time Emmy for various parts of “War and Remembrance.” In 2003, he was honored with the ACE Career Achievement Award.

By then, Burnett had retired to his ranch in Lincoln, Calif. In the 1990s, Burnett began stepping back from feature films and transitioned to episodic television in order to care for his wife Rosemarie, then ailing with cancer. Following Rosemarie’s death in 1998, Burnett remarried to Marjolane, known as Margie, who had been Rosemarie’s best friend and the maid of honor in John and Rosemarie’s marriage. “It was a good thing, because they had everything in common,” John Earl Burnett said. Margie died in 2018.

John F. Burnett is survived by his brother David and his sons with Rosemarie, John Earl Burnett and Stephen F. Burnett. ■

— Peter Tonguette