by Peter Tonguette

From early in her career in the film business, Jeannette Browning recognized that she was something of a rarity. “I was really interested in dubbing, but I realized that there were no female dubbing mixers,” she says. “I thought, ‘Maybe if I succeed, I could be one of the first female dubbing mixers.’ It’s the kind of cool stuff you think about when you’re invincible and young. And then reality hits you.”

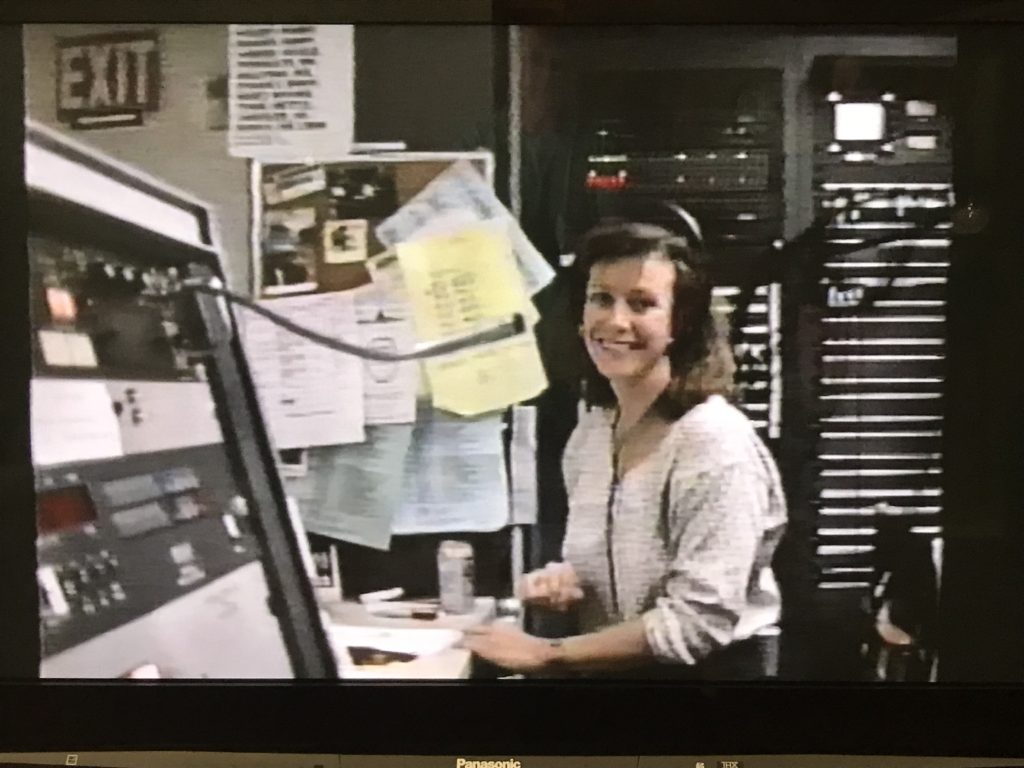

As she tried to gain a foothold, Browning ran into some roadblocks but ultimately found her place in the business as a recordist. Since the early 1990s, the successful dubbing and ADR recordist has made her professional home at Walt Disney Company.

On her very first union film, Robert Redford’s The Milagro Beanfield War (1988), Browning encountered two women whom she saw as role models on the journey ahead: picture editor Dede Allen, ACE, and supervising sound editor Kay Rose.

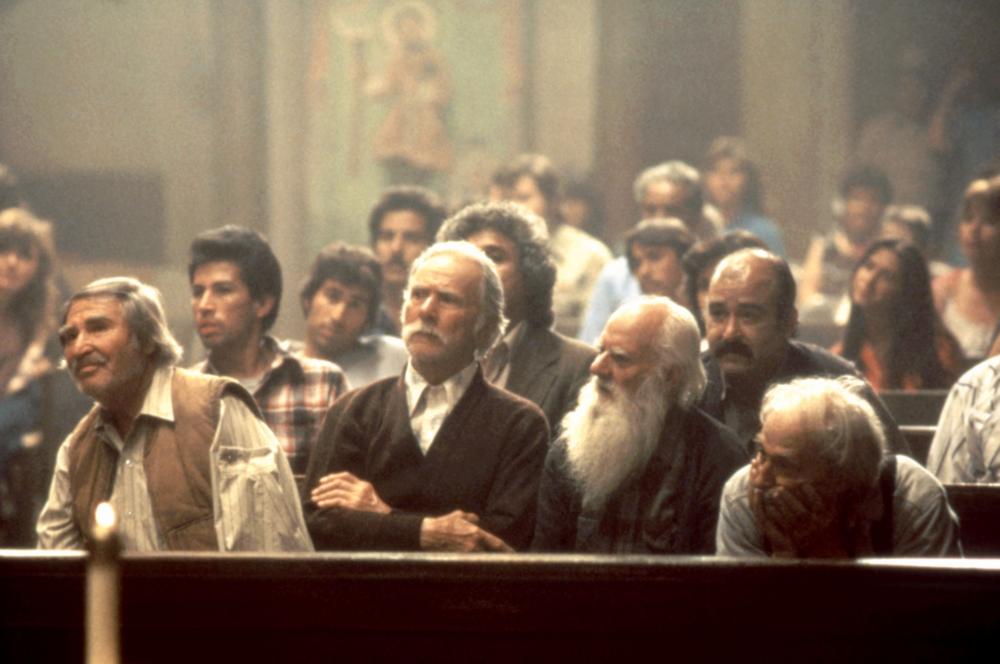

While working at the recording facility Sound One in Los Angeles, Browning served as the projectionist/dummy loader on Milagro. The Universal Pictures release unfolds in a made-up town in New Mexico, where a mercenary developer (Richard Bradford) finds himself locking horns with a mild-mannered farmer (Chick Vennera) in a fight revolving around the local water supply. The film featured Rubén Blades, Sonia Braga, John Heard and Christopher Walken in supporting roles.

Equally important to Browning, however, were Allen (who collaborated on the film with Jim Miller, ACE) and Rose. “You hear about the challenges women face in a predominantly male workforce, but these ladies had done it, so I felt, ‘OK, I can do this,’” Browning reflects. “It gave me hope and inspiration.”

As Browning tells it, the legendary picture editor and equally revered sound editor were supportive and nurturing colleagues. “They were quite delighted to see a woman in the machine room,” she says. “I felt the respect and the appreciation went both ways. They were very kind to me, they shared stories and I learned all sorts of interesting things.”

A native of the San Gabriel Valley, Browning was a film buff as a youngster but decided to pursue accounting and pre-law while a student at UCLA — up to a point, that is. During her senior year in college, she switched gears to marketing and advertising. Then, following her graduation in 1981, she found work as a driver for a trailer company, Cimarron. “They made the coming attractions for the films,” she explains. “I loved those, and sometimes they were the best part of going to a movie. We’d count how many we got to see, and then how many of those films we’d want to go see.”

Although she enjoyed her time as a driver and glorified “film schlepper,” Browning was grateful when an opportunity arose for her to contribute creatively at Cimarron. “The sound girl — that’s what it was called then — left,” she remembers. “I did the transfers from quarter-inch to mag from the narration sessions, and one-to-ones of the production work tracks. I ended up building a sound room with a console, patch bay and speakers.” Immediately, she connected with the musicality inherent in working with sound. “I played piano growing up, so it was familiar,” she reflects. “I loved music. I also felt that trailers were an emotional rollercoaster ride totally driven by sound. It was all about the sound, and how it was utilized, to get you to want to see that movie.”

Browning immersed herself in post-production, taking classes at UCLA and Los Angeles Valley College, and eventually landed at Sound One where Milagro was mixed. It represented her first project as a member of IATSE Local 695 (the sound technicians guild, whose post-production members merged into Local 700 in 1998). “I joined the union as a Y9 recordist position, but on Milagro another fellow employee was the recordist and I was the projectionist/dummy loader,” she explains. “I was responsible for the machine room, the playbacks and the projector. I was just thrilled to be on the show.”

Rose, whose credits as a sound editor include acclaimed films by directors Peter Bogdanovich, Mark Rydell and Martin Scorsese, left a vivid impression on Browning during their time together in the machine room. “She’d come up with a cigarette dangling in her mouth,” the future recordist recalls. “We’d run up to get her an ashtray, but Kay said, ‘No, no.’” Then, when Rose wanted to review a track, she instructed the crew to leave it on the machine. “She’d just tap her cigarette on the track where the gate mark had been made and walk away,” she continues. “I was like, ‘What was that all about?’ Then we’d hear over the intercom, ‘OK, that’s better.’ There had been a click, a snap or a pop on the audio track, and she just got rid of it with a little cigarette ash. That was not something you would learn in film school; she didn’t even have to bench it.”

“We pre-dubbed the dialogue, then the ADR, the backgrounds, the Foley and the sound effects,” Jeannette Browning explains. “Then the music came in and we put all of the pre-dubs up with the music elements, and start mixing the final master stems.”

Browning also heard Allen explain how she contributed to the shattering of glass ceilings on Bonnie and Clyde (1967) at Warner Bros., despite the opposition of studio head Jack Warner. Enter producer and star Warren Beatty. “Dede told us about working on the film and getting locked off the lot because, to quote Jack Warner, ‘No woman was going to cut any of my films,” she recalls. “She called Warren Beatty from the Smokehouse Restaurant and said, ‘I can’t get on the lot.’ He said, ‘I’ll be right there,’ and went over and brought her on the lot. Needless to say, we all know she cut that film.”

From a recording standpoint, Browning remembers Milagro as a very typical show. “We pre-dubbed the dialogue, then the ADR, the backgrounds, the Foley and the sound effects,” she explains. “Then the music came in and we put all of the pre-dubs up with the music elements, and start mixing the final master stems. It was a 4-track back then.” Each evening, the team had to be ready for playback for Redford, who, earlier in the decade, had been honored with a Best Director Oscar for Ordinary People (1980). “There was pressure because he was Robert Redford, but he ended up being so nice, calm and relaxed,” she says. “When we called him ‘Mr. Redford,’ he said, ‘It’s Bob.’ And we all went: ‘OK, Bob!’” The teamwork at the facility paid off, however. “We had our A game,” she adds. “We had very fast and efficient reel changes.”

Although The Milagro Beanfield War received tepid notices from critics, and failed to ignite at the box office, the film received its due as far as sound was concerned: Composer Dave Grusin received an Oscar for his score. For Browning, the impact of the film was incalculable. Following several short-term gigs, including a second stint at Cimarron and a position at Universal, she found her way to Disney, first in sound transfer, then as the recordist in the main theatre and finally on the ADR stage. Her films as an ADR recordist at the studio have included M. Night Shyamalan’s Unbreakable (2000), Gore Verbinski’s Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End (2007) and Steven Spielberg’s Ready Player One (2018). “Getting into the union opened doors,” she comments. “The first time I thought I was the luckiest person in the world was when I got put in the main theatre. I thought, ‘Oh my gosh — this is the stage where Fantasia was dubbed.’ And the projectionist/dummy loader, and my co-worker ,was a woman!”

The recordist never worked again with Allen or Rose, but did get a chance to reunite with Redford when the two crossed paths on his subsequent directorial effort, The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000). On that project, the opportunity arose for her to express her appreciation to the filmmaker. “I thanked him so profusely for bringing Milagro to Sound One,” she comments. “I said, ‘You got me in the union and I’m here now.’ He said, ‘Well, that’s wonderful. I’m so happy for you.’” Browning couldn’t let the director leave, of course, without getting a few autographs for assorted family members. “I said, ‘Would you sign something for my stepmom and my aunt?’” she adds. “He said, ‘Sure.’ I had these 8×10 pictures of him from years before and he signed them, which was really cool.”

More than an autograph, however, Browning got a career out of The Milagro Beanfield War. “It was the film that changed my life,” she reflects. “I would like to think that if it hadn’t been that film, it would have been something else. It could have been this or it could have been that — but it wasn’t. This is what happened, and this is where it has led me. And I am very grateful.”