by Peter Tonguette

You might call Jonathan Mostow’s action thriller Breakdown a cautionary road movie.

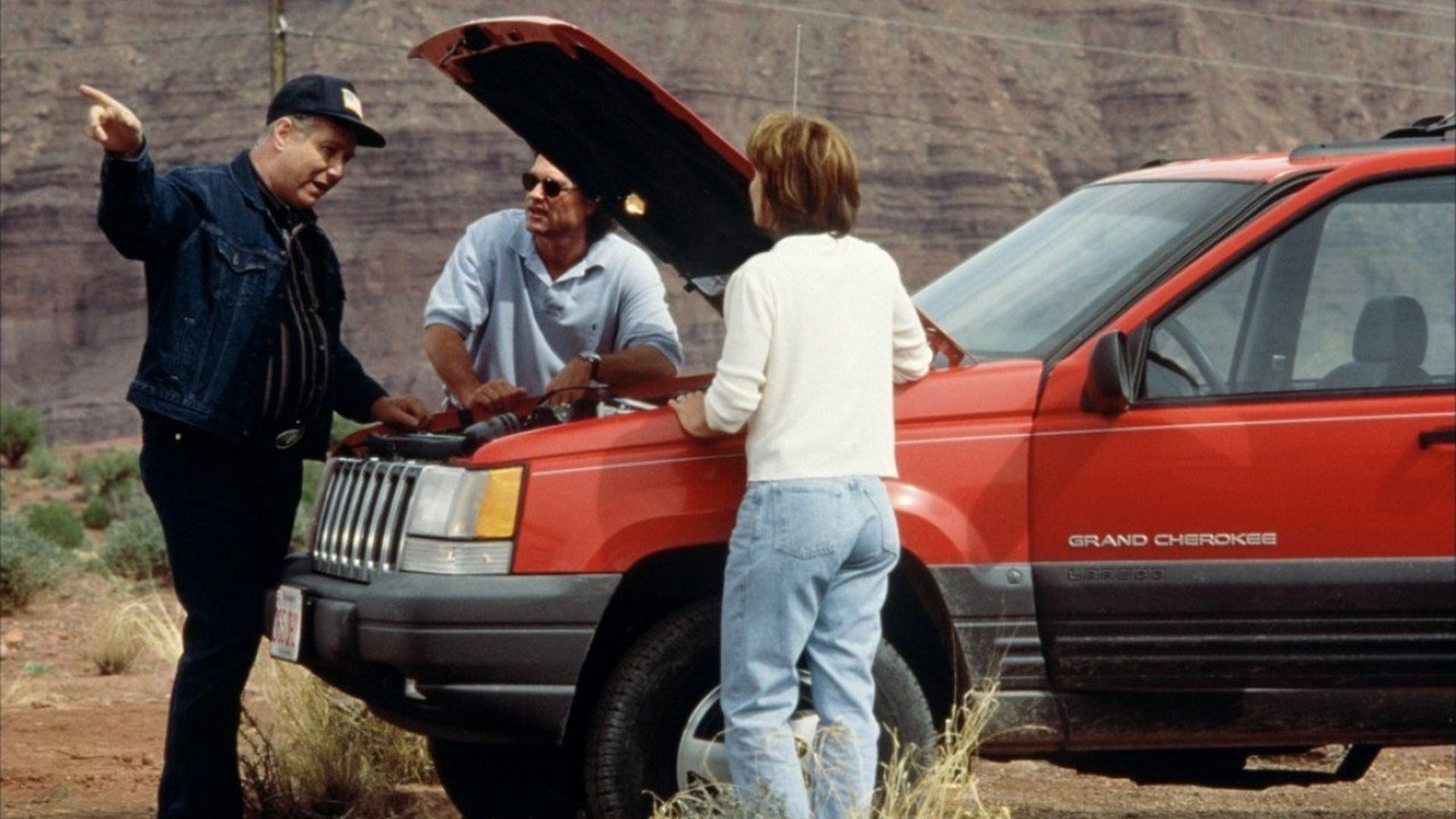

The 1997 Paramount Pictures release centers on a car trip that takes an unexpected detour: Having decided to relocate from Boston to California, married couple Jeff and Amy Taylor (Kurt Russell and Kathleen Quinlan) are winding their way through the desolate environs of the American Southwest before their Jeep Cherokee stalls. Truck driver Red Barr (J.T. Walsh) spots the Taylors and suggests transporting Amy into town to retrieve roadside assistance. Amy gets aboard Red’s 18-wheeler, while Jeff stays put to wait for help.

If things were that simple, of course, there would be no movie. Soon after parting with Amy, Jeff finds a way to get his Jeep started, but when he arrives at his wife’s intended destination, he is unable to locate her. Meanwhile, Red insists that he has never met the hapless out-of-towners. A series of heart-stopping chase scenes — ones that led New York Times critic Janet Maslin to compare the film to Steven Spielberg’s Duel (1971) — follow as Jeff uncovers the conspiracy into which he and Amy have driven.

For audience members, the film offers several takeaways. For starters, maybe it is best to stick to highways on that next road trip. And, if the offer of a ride sounds too good to be true, it probably is — especially if an actor as quietly menacing as Walsh is making the offer.

But for supervising sound editor Jon Johnson, Breakdown provided a different set of lessons. Early in the process, Johnson — who was suggested for the film by producers Dino and Martha DeLaurentiis, who had worked with him on John Dahl’s Unforgettable (1996) — was asked to prepare a demo reel to show to prospective distributors.

“They were trying to sell the film and they sent me the section where J.T. Walsh first gets pulled over by Kurt Russell,” Johnson remembers, referring to a scene in which Jeff confronts Red. “I got it and decided: ‘Oh, it’s a truck film, so it’s going to have some CB radio and traffic on the road.’ Jonathan was still shooting at the time, so we put this together and I sent it over.”

Mostow, who was seeking an eerie, spare soundscape for much of the film, reviewed the reel and judged it too cluttered. “He said, ‘What is all this CB stuff?’ This isn’t what we needed at all,’” Johnson remembers. “I went back, re-crafted it, put in the wind and adjusted a few sounds here and there. That pretty much became the framework of the film; it was really about the isolation of these characters. There were no other people talking to them.”

The experience was instructive. Johnson, who would later collaborate with Mostow on four additional films, recognized that the absence of sound — especially human sound — can be a useful tool in telling a story. “I discovered that your ear immediately goes to a human voice, especially on a radio or if you hear a baby cry in the background,” Johnson explains. “It can be something useful, but if it’s not motivated, it will stick out before all the other sound effects.”

A native of Wyoming, Johnson majored in film and television at Montana State University, where he counted among his classmates future collaborator Dahl (with whom he worked on six films, including 1994’s The Last Seduction and Unforgettable). “It was a small department and it was powered by your peers,” he recounts. “The word got out that basically you were making movies from day one. You’d make silent, then you’d work in 16mm with a non-sync soundtrack, and then the final would be a 16mm project — at least 10 minutes in length — and it would have sync sound. It was a good place to be trapped in because it can get pretty cold there, too. There were no distractions.”

Following graduation in 1978, Johnson moved to Los Angeles, where his early jobs included stints at Neiman-Tillar and Associates, Hanna-Barbera and Glen Glenn Sound, where he was a supervising sound editor. “They had one of the first multi-track editing systems,” Johnson says. From 1987 to 1989, he worked at Modern Sound, where he became proficient in the Synclavier digital system. “It was still a music-heavy device, but it was a great creative tool and had a fairly steep learning curve,” says Johnson, who in late 1989, set up his own shop, Fury & Grace.

“At that time, if you had a company in sound editing, you had a minimum of maybe 15 or 20 people,” Johnson reflects. “Well, for me, it was just me. I started with one and then branched out. We had a pretty small crew, but the people stuck with me for a long time.” Early employees included sound editor Michael Chandler and dialogue editor Robert Troy, both of whom were still with Fury & Grace for Breakdown.

Because Breakdown was cut on film, when Johnson began reviewing the material, the sound was housed on a single track. “It wasn’t like a screening now where you would have a music track and an effects track,” he says. “It was mostly dialogue.” The sound editor soon realized just how many sounds he would be responsible for creating. “I remember screening the big chase scene and up on the screen is this incredible mayhem, but the theatre was absolutely silent,” he comments. “It was the first time that I really started to get apprehensive. It was sort of like looking at the Rocky Mountains and you have to chop down every tree; where do you start?”

To build a library of sounds for chase scenes, Johnson accompanied a stunt driver to the desert to record while aboard a Ford F-250 truck. “It was so hot that the air conditioning was breaking down,” he remembers. “I had Reebok sneakers on and the soles of my shoes had become unglued. They flapped like clown shoes. But we recorded some incredible stuff. He jumped the truck and did peel-outs, showering me with grit while I dodged baseball-sized rocks coming off the rear tires.

“Once I had the body of that stuff, and the core of the sounds for the cars, I knew the chases would be just the good bits,” Johnson continues. “I had a fairly large library of that.” Sounds were also recorded while aboard multiple semi-truck and trailer beds. “Pretty much stuff I didn’t divulge to my wife at the end of the day,” he adds. “Kind of scary in the recording, but great sounding!”

Although Mostow sought a subtle soundscape for some scenes, the director did not hesitate to try for bold, booming sounds when necessary. “If we’re going to go for it, we’re going ham-fisted,” Johnson attestss. “That was something we did on the other films that we made together. If we were going to do something loud, like a big chase, we tried to get it as quiet as possible before we started off on all of the fireworks.”

In one especially explosive scene, Jeff and Amy are pursued by not one but three bad guys: The couple is followed by Red’s 18-wheeler and flanked by two of his criminal cohorts, one driving a Pontiac Firebird. Johnson looked to the on-screen action as a guide for what track to use; if a shot focused on one vehicle, the audience would hear that particular vehicle.

“Because it was in 5.1 [surround sound], I was really concerned about what was going on off-stage with each of these vehicles,” Johnson recalls. “When you cut to the Firebird, I’d have that track, but I’d keep it in the background if necessary.” Today, Johnson might place the Firebird track in the left surround, but in the mid-‘90s, “It would have just muddied up the track,” he says. “It wasn’t something you could focus on because the cuts were coming so quickly. You’d just be making more racket rather than engaging the audience, so it just became cut to cut to cut rather than something ongoing.”

Johnson also found that audiences grew bored with the constant hum of an engine. “You’re doing a constant trade-off between tire skids and the squeals and all of these other things you need to have,” he says. “That engine can’t be steady. It’s got to be climbing and doing things, so it’s like an active chorus of sorts.”

Another standout scene finds Jeff grasping the side of Red’s 18-wheeler while the truck is being driven. “We had two great Foley guys working with us — Bob Rutledge and Ed Steidel,” Johnson says. “They brought so much to the table in that instance. They came up with the chains and big burly stuff like that, and then we’d sweeten it.” The sound editor also credits picture editors Derek Brechin and Kevin Stitt, ACE. “It really started with Jonathan’s ideas and the way Derek and Kevin put it together,” he says. “It’s so much easier to do sound in something that’s well-cut. You’re not trying to bolster something that’s not there, and it just leads you from one decision to the next.”

The kinetic action was also helped by what ended up being a minimalistic, often unobtrusive score by composer Basil Poledouris. “Paramount did not like the original score that Basal came up with,” Johnson remembers. “The entire time, he was trying to put things together. But I think it actually helped the film that it was a lot simpler — sometimes it would just be pipes and drums or a whistle and drums.”

Despite the false start with the demo reel, Mostow was pleased with his supervising sound editor’s contributions to Breakdown. Johnson recalls a memorable cast-and-crew screening also attended by Mostow’s wife. “Jonathan’s wife at the time was very pregnant, and the next morning she gave birth,” he says. “I always say, ‘It had to be the subwoofers.’” The director and supervising sound editor would reunite on U-571 (2000), for which Johnson received an Academy Award for Best Sound Editing, and again on Surrogates (2009) and The Hunter’s Prayer (2017).

In addition to cementing his bond with Mostow, the film also elicited praise from Johnson’s colleagues. “[Sound editor] Steve Flick called me and said, ‘Boy, I really like the work you did on that,’” recalls Johnson, who is currently an in-house supervisor, sound designer and sound mixer at King Sound Works. “That was the first film where people called me. After scratching around for six years in my business, and then getting a little bit of recognition, really felt great.”