By Patrick Z. McGavin

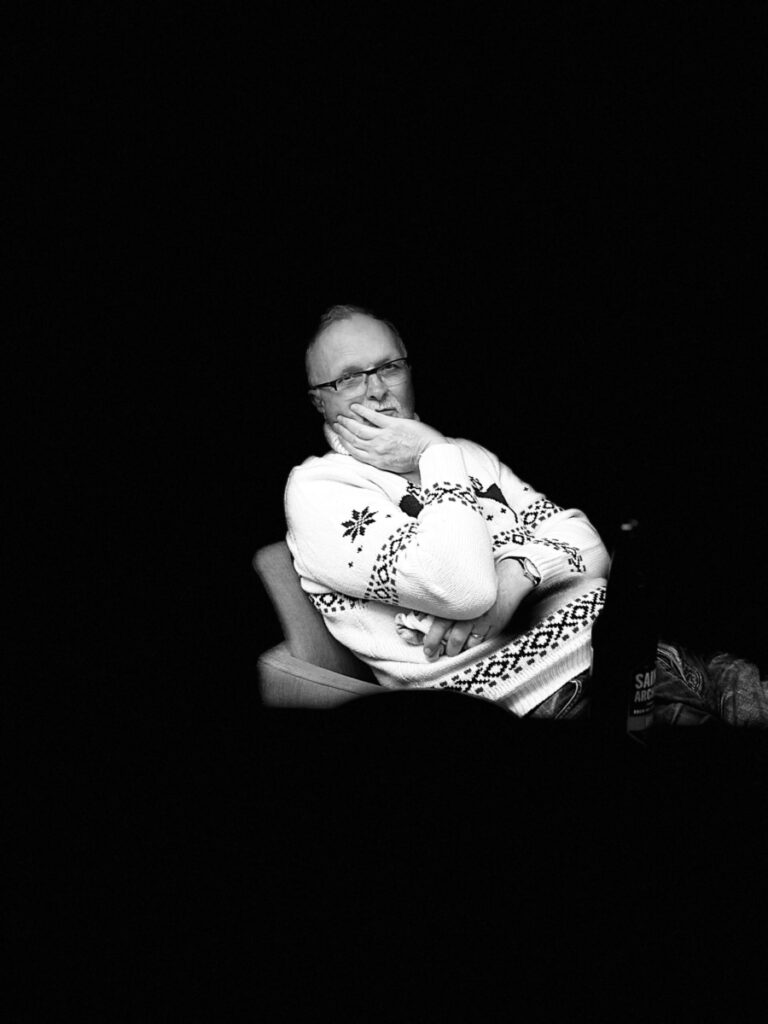

Time and opportunity converged happily in the life and art of Lee Smith, ACE. Born in Sydney in 1960, he came of age as a teenager during a propitious moment—the rise of the Australian New Wave national film movement.

Films like Fred Schepisi’s “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” (1978), Gillian Armstrong’s “My Brilliant Career” (1979) and Bruce Beresford’s “Breaker Morant” (1980) made visually unforgettable the country’s beguiling landscapes and complex, traumatic national history.

Smith’s first significant credit was as an associate editor on Peter Weir’s political thriller, “The Year of Living Dangerously” (1982).

“Meeting Peter Weir changed my life for the better,” Smith said. “Without knowing it as a young person in the industry, the one thing I did know was what transported me. Working with him gave me my whole creative thought process.

“Beresford I worked with, and I met Schepisi, and saw all of his films. Gillian Armstrong and Jane Campion. They were some truly remarkable films made back in the day in Australia.”

Weir gave Smith his career breakthrough as the lead editor of “Fearless” (1993). Their subsequent work, “The Truman Show” (1998), showed an expanded range and versatility.

A three-time nominee for best editor, Smith won the Academy Award for best editing with Christopher Nolan’s World War II film, “Dunkirk” (2017).

If Smith’s collaborations on Weir’s “Master and the Commander” (2003) or Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy showcased his deft abilities negotiating large-scale action epics, the director Sam Mendes has encouraged him to push new technological frontiers.

Smith’s first project with Mendes was the James Bond movie, “Spectre” (2015).

In Mendes’s World War I story, “1917,” Smith achieved a remarkable virtuosity and flair by suggesting the entire harrowing, kinetic film was shot in a continuous, unbroken two-hour take.

Choosing a director is more important than the film itself.

“If you have the good fortune to cross their paths, or get invited to work on their films, it’s important, as an editor, you generally enjoy the films they make, and you can appreciate a lot of what makes those films interesting.

“When you make them, you discover whether you are like-minded people, because you’re going to be spending a lot of time with them.”

Now the director and editor are back again with “Empire of Light,” a moody, emotionally intricate love story set in 1981, in the British seaside town of Margate.

Olivia Colman plays Hilary, a duty manager at the Empire Theatre, a beautiful art deco movie theater palace. Sexually manipulated by her boss (Colin Firth), Hilary finds newfound emotional comfort with aspiring architecht Stephen (Michael Ward).

Their taboo-breaking interracial relationship is further complicated internally by Hilary’s mental health struggles and larger political unrest of the racially tense Thatcher era.

“It was exciting because this is much more of a character-drama piece that also relies heavily on atmosphere and mood,” Smith said.

“I have always been attracted to films that can do that, the ability of a film to not be a giant blockbuster, action movie, that can take its time and sit with interesting characters, and be genuine in how it draws you in.”

CineMontage: Was your collaboration with Sam Mendes a continuation of your existing creative relationship, or did you mix things up a bit this time?

Lee Smith: It did continue the course we set right back with “Spectre.” Different directors have different processes and methodology. I have worked with great directors who don’t want to see any edited material as they’re shooting because of what they’re going through to get what they want unless I hold my hand up and say, “We have a problem, and we need to address it.”

Sam loves to review materials while they’re shooting. He is totally keen on seeing the progression of the cut, all the ideas are flowing backwards and forwards as they’re shooting. It’s a unique way of working. When we get to the post-production process, we kind of already arrive at the first cut of the movie. It plays like a movie from that moment, generally just refining things.

CineMontage: The early movements map out the interior life of Hilary. Did you want the cutting to underscore her social isolation?

Lee Smith: That’s exactly what it is. It’s also the isolation of working at the cinema, and preparing it for its daily use. Her whole world and her interactions are within the close house that was that cinema, with all of those slightly strange and eccentric characters.

It was so reminiscent of people I have worked with. I could put names to all of them. I didn’t work in a cinema, but just being in the business with projection and things like that, working with people with a love of movies, to work in that environment, sneaking a peek at movies, would be part of the reason you’d work in a cinema these days.

CineMontage: Hilary has this double sexual entanglement, the first one feels very coercive, and the other is liberating but also socially taboo. The editing really contrasts those differences?

Lee Smith: Obviously she was in an abusive relationship as far as her relationship with Colin’s character. There was nothing remotely sexy or romantic about that. He was basically taking advantage of someone who was lonely and needed affection.

The flip of that was someone who was just incredibly caring and gentle, and had been raised by a wonderful person in his mother. It was the difference of care and love as opposed to the simplicity, aggression and power of sex. It was two opposite ends of the spectrum.

When you first watch it, you may well wonder what’s going on. As the film progresses, you understand how Olivia responds when she is in actual love rather than being used in a sexual manner.

CineMontage: Do you have any interaction with cinematographer Roger Deakins? Was the film storyboarded?

Lee Smith: I don’t think I saw a single storyboard on the film. I don’t normally look at storyboards. I like to just edit from the materials. Different people have different processes, and they love editing storyboards together. I have to deal with what’s shot. Unless it’s a highly choreographed, complex visual effects sequence, the storyboards are a guide at best.

All the truly great directors are organic. Even if you have storyboards, you step outside of that to capture whatever is happening on the day. That fluidity and organic nature is what makes a film great.

CineMontage: The use of songs is really interesting. You have the Bob Dylan song, “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” which is very emphatic and direct, and the more allusive Cat Stevens’ song, “Morning Has Broken,” which is muffled, almost whispery.

Lee Smith: The Cat Stevens one was Sam’s idea. We were using something else for a while, and it wasn’t quite working. The music in this film is definitely a player. We’re not just dropping music in to fill a void. All of those cues serve an important purpose. One night Sam mentioned as he was driving home from the shoot. We pulled it off the Internet, and stuck in the scene. I sent it back to him, and I think I typed, “Wow.” I don’t know what it is, but that track just killed it.

I am never sure if it’s my age, or the places I attended, or the music I listened to, and music like this is incredibly subjective. These cues we used in the film were like 100 out of a 100. I can rarely say that in a movie, “Man, that works.”

CineMontage: How did you approach the right-wing street demonstration that turns into a violent episode inside the theater lobby?

Lee Smith: I think the decision was made earlier to play the entire scene from inside the cinema. It was like having your house invaded.

Rather than doing all of this coverage of the skinheads coming down the street, I think having it shot from the perspective of the theater makes it more terrifying. It was interesting playing Hilary’s point of view of witnessing all the raging skinheads of Steven being jostled and then attacked.

It was an usual thing. It felt very real, almost like a documentary, watching the dailies and everything. It was quite frightening to watch.

Very realistic, and not like an orchestrated set piece and thousand and one things were happening, and you were detailing everything. People just get lost in the melee. I enjoyed the simplicity of that.

CineMontage: Did working on this film make you reflect on your career? Do you miss the more artisanal aspect of working with film?

Lee Smith: There is a lot I miss about it. I don’t miss the handling of film. I miss everything else about film. From an editing standpoint, film is destructive. You’re literally putting a blade through it.

Changing your mind or making adjustments is like rebuilding a house that you continuously knock over with a sledgehammer. Editing nonlinearly you can change in a split second, and basically have multiple versions running. From an editing standpoint, that was liberating.

I just grew up handling film, and working on moviolas, projecting, and traveling the world and going to labs and going through the whole thing. I think the most marvelous thing in the world is watching the dailies the day before shoot when they’re processed.

When you shot on film, you sometimes didn’t know what you got. It was like opening presents on Christmas Day. You don’t know what’s in the box, and you’d sit there and watch it. Fifty percent you’re just relieved that there is exposure on the negative. That’s not detracting from the cinematographers, but there were a million things that could go wrong.

Nowadays, shooting digitally, you know you have it from the second you shoot it because you can play it back. That takes a little bit of the angst out of it. Maybe it’s rose-colored glasses, but there was something organic about celluloid that was wonderful. My memory as a young teenager was endlessly going to see films, and being transported away.

Patrick Z. McGavin is a Chicago writer and cultural journalist. He maintains the blog “Shadows and Dreams” (www.patrickzmcgavin.substack.com).