Farrel Levy, ACE and Stan Salfas, ACE have worked on a wide range of projects, from features to documentaries to movies-of-the-week. Both started their careers in New York, then moved west, where they eventually became supervising editors on noteworthy television series: Levy has been with NYPD Blue for nine years, Salfas with Felicity for four. They have had the chance not only to shape the character of their shows but also to direct. In this, the first part of their conversation, the two talk about television as a medium, why it can be fulfilling for an editor and how they nurture the work of their assistants.

Levy: When I got my first job as a television editor, I was offered an independent feature to cut or a chance to work for Steven Bochco. I weighed the pros and cons and thought, I really have enjoyed watching Steven Bocho’s television shows. I would carve out that time in my week and watch those.

Salfas: Appointment viewing.

Levy: And someone had also said to me, “Bochco’s very loyal.” So I decided I would go and work for Bochco. But I did find myself feeling somewhat defensive toward my friends who were in the feature realm. Like it was somehow lesser, being in TV.

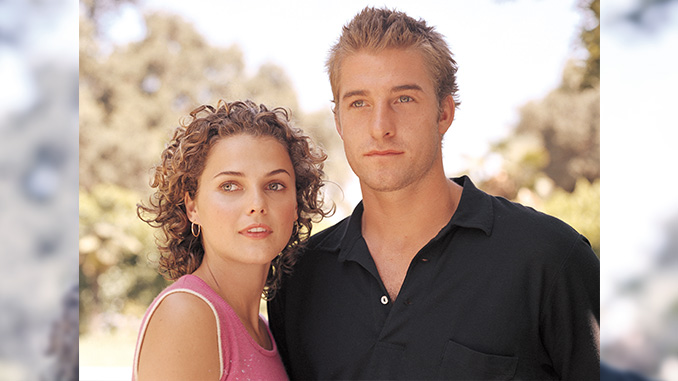

Salfas: That’s how it’s perceived — television editing is one thing and feature film editing is something else. I had some reservations about doing a television show. The executive producer of Felicity is Matt Reeves, who directed The Pallbearer, a film I edited. In the process of doing that film, we got very close in terms of the kind of story-telling that we were interested in. So when he and J.J. Abrams set out to do the Felicity pilot, they asked me to edit it. I hadn’t done much television, but I really felt it was an opportunity to work closely with those whose aesthetics I love, and whose creative goals I share. We did the pilot, and it turned out to be very successful. Then they started the show, and they asked me to come on. I did it on a temporary basis, thinking I wouldn’t necessarily stay. Then they offered me an opportunity to direct, and that was very important to me in a lot of ways and gave me another level of opportunity that I hadn’t had before. And they both have done pilots since that I’ve edited — Gideon’s Crossing and Alias. So, I’ve basically worked either with Matt or J.J. exclusively for the last four years, and I enjoy that.

“We aspire to an editing style that is as invisible as possible. What we’re interested in is the expression of naturalistic emotionality; we’re trying to clear everything else away.” — Stan Salfas

Levy: I found, working for Steven Bochco, that I have truly come to appreciate TV as an important medium to work in. I have an art school background, and one of the things that was dissatisfying about being an artist was that I always wanted to do something that reached out and spoke to large numbers of people. That is what originally got me into film, but I feel that TV does that even more. If you’re working on a successful show, over the course of the life of that show, those characters, those stories, make a deep imprint on people’s minds. I enjoy helping to create stories that are part of the American popular culture in a way different from films, but just as legitimate. In doing good series TV, one is creating the contemporary equivalent of a Charles Dickens installment story. People care about the NYPD characters. People want to know what’s happening. People are in sync with what goes on week to week.

Salfas: Television is in your home. For most people, it’s part of their lives. When I go to a movie, I’m going out to see this one thing. A lot of people empathize with Dennis Franz as Sipowicz. They’re very interested in the life of that character. I remember there was an article in the New York Times Magazine a number of years ago, and it talked about what was the most potent contemporary literature. And the article said it was Law and Order, NYPD Blue and, at the time, Homicide — that was where the consistently best writing was in the culture, and I think there’s some truth to that. Certainly, not every episode that you work on is as well written as every other. But the quality of writing that you get to deal with is often better than on many of the films I’ve worked on.

Levy: One thing that makes a good television show so much fun to work on is that it is a writer’s medium. But unlike a lot of features, it’s not re-written by many different writers and managed by the studios and audience preview process.

Salfas: You don’t have preview cards.

Levy: With Steven Bochco and David Milch, the show is their voice. It’s a direct line from the writer to what we edit, and the writer ultimately is the one who has the final say.

“NYPD Blue’s style came out of certain TV commercials and a little bit of MTV. My approach has been to tell the story and keep it visually interesting, but not let it get over-cut and confusing. It’s allowed me to explore and understand a new sort of visual language.” — Farrel Levy

Salfas: I’m very interested in the writer’s voice. If you look at a show like Felicity closely, you’ll see that it’s about a certain kind of truthfulness in relationships and the conflicts of trying to be a moral person in a difficult and fast-changing world. One of the reasons I got into film was to try to bring positive things into the world. I don’t say that every episode does that, but on the whole, one of the reasons the show is so respected is that it has a unique voice. As a co-producer, I have a lot of responsibility in post-production on the show, so I’m instrumental in making that voice articulate. The editing style is a big part of the naturalism and the level of reality that we try to achieve. I find that very satisfying compared to some experiences that I’ve had on feature films.

Levy: Ultimately, we don’t have the final say. But there is a dialog, and the thing that I like about series TV is that it’s very much a process. You give an opinion — sometimes it’s accepted, sometimes it’s not. But then, there’s the next show. That’s something that’s very exciting about television: it’s not that any show is diminished in the amount of work or attention that goes into it. But there’s a little room for experimentation because you know that there’s going to be another one. Or if something doesn’t work quite so well, it’s not the only shot that you or the writers are going to have.

Salfas: You don’t have a fear about every cut. If you’re working on a film, how many cuts are there? I worked on The Pallbearer for a year. And I’ve been on a number of films that have been in post-production that long. But in one television season, you’re creating about 22 hours in nine months. I am personally editing seven or eight of those hours, and I am reviewing all the rest of them, and sometimes going in and working very closely with the editors on a cut-by-cut or scene-by-scene basis. Sometimes I associate it with learning how to play the piano. You could spend six months learning a piece by Rachmaninoff, or you could sit down and work on a Chopin prelude that is only one page. It has as much emotional complexity, and it is as demanding in certain ways, yet you can finish it and move on to work on something else. And, I find that in certain ways, I’ve grown more quickly than I might have working in features. I’ve had to work more quickly. I’ve been willing to take a lot of chances. I can say what I think, because I rarely have the luxury of time to hesitate or second-guess myself. You’re in a situation where you have an air date two, three weeks down the road, and the producer or writers turn to you, saying, “This scene doesn’t work. What do you think we should do?” And you don’t have time to say, “Give me a couple of days, we’ll work on it.” You have to say, “We should try this and this, and let me just do it.”

“When we set up our show, I made it very clear that I wanted four Avids, so the assistants would have the opportunity to edit.” – Stan Salfas

Levy: Because of the sheer quantity of the work, I’ve gotten very good at coming up with alternatives. You used a music analogy — I often think of it as doing many fine drawings, as opposed to one painting. It can be very freeing. The quantity of TV shows being cranked out has some interesting by-products. I think that because television offers a chance to be more experimental from an editing point of view, over time, this broadens what is considered acceptable to the audience, and it will broaden the way we tell stories. And we’re able to experiment with technology. Bochco was one of the first people to try the Avid. Ten years ago, they asked what my feeling was toward this new editing system. I have a brother who works in commercials in New York, and he had used an Avid and thought it was the greatest thing, so I was game to try it. We had a chance to be a beta site. We trained for a week, and I fell in love with it. It was tricky to learn, but I never want to be in a position where I won’t try something new. I thought I’d better get with the program and get with it early. We now broadcast in high-definition. What’s interesting about that is that the post people on all the hi-def shows are brainstorming and helping each other, because everyone’s feeling their way a bit. They’re not being territorial about the knowledge.

Salfas: We’re on a baby network, so we shoot on 16mm. They tell us to protect for HD, but we’re not broadcasting HD, so we don’t edit in an HD format. We don’t look at 16×9 in the editing room.

Levy: We don’t either. I was worried last year, knowing that the show was being broadcast in both aspect ratios and we were not seeing the 16×9 version. The producers really like to see it in the old-fashioned format and it’s very difficult to do both. But, we do have someone that checks for matches in online and makes blow-ups, if necessary.

Salfas: For the benefit of people who don’t work in television, what is your routine?

Levy: On our show, we often get over three hours of film a day — 18 reels or more. And we have to come out with a finished cut just a few days later. We shoot in eight days and then have two or three days after the end of shooting, which includes the last day of dailies, to come up with an editor’s cut.

Salfas: We have about the same schedule.

“You give an opinion — sometimes it’s accepted, sometimes it’s not. But then, there’s the next show.” – Farrel Levy

Levy: So we have to get used to looking at dailies, evaluating them and getting a story together in a very short amount of time. You have to get really good at looking for the best performance, getting that down and working quickly. And I think that’s an advantage of TV editing. We become very decisive and make fast decisions. You go with your gut, and it’s often the right way. Not that I don’t do alternatives — I do. But because of our fast turnaround, the editor really makes a template for the whole show. What we do initially often doesn’t change a whole lot.

Salfas: There’s no time for it to change, really. That first cut has to be very strong, because there’s not a lot of time to rework things. On a movie, you can rework everything. It’s assumed that you’re going to do that. But on a television schedule, your first cut has to be very close to what that final version is going to be. What is normally changed has much more to do with overall things — with story, with length. Does the show work or not, and if not, then how do you make it work? You move very quickly to structural problems, which are incredibly interesting. Because of a certain performance, you’ll suddenly find that the whole show, which was supposed to be about one thing, has turned out to be about something else. Of course, that happens in movies, too. One of my favorite stories when I was in film school was about Klute, which started out to be a movie about Donald Sutherland and ended up being about Jane Fonda. I remember hearing that story and thinking that editors can transform the intention of a film. It’s exhilarating to have that kind of freedom — to play with your material in global ways.

Levy: It’s been very exciting for me to work on a show with a unique style like NYPD Blue. When it started, I think Homicide was the only show with an off-beat style. Our style came out of certain TV commercials and a little bit of MTV. My approach has been to tell the story and keep it visually interesting, but not let it get over-cut and confusing. It’s allowed me to explore and understand a new sort of visual language. I’ve been doing it now for nine years, and it’s gotten very simple for me, but I know there are a lot of people who are still learning how to work with that kind of material. I think I understand what it’s about visually, and one of my jobs as supervising editor is to train new editors in the style of the show. The stories are very detailed, the production design is very dense and the camera work is very active. There are a lot of things happening in the frame. Too much cutting takes away from the story telling.

Salfas: Our show couldn’t be more different visually from NYPD Blue. We aspire to an editing style that is as invisible as possible, as if you were looking into a pond that was completely clear and you could see through the surface of the water to what’s happening beneath. What we’re interested in is the expression of naturalistic emotionality; we’re trying to clear everything else away. We try to create the illusion of no editing. It’s a very difficult style, and it takes a lot of time and requires a tremendous sensitivity to the rhythms of the show. Doing that on this kind of schedule is extremely difficult.

“[In TV] You don’t have a fear about every cut.” – Stan Salfas

Levy: A big difference between television and features is that our cutting rooms are often very close to the stage, so there’s a lot of communication between the editors and the crew. In features you can be in another city or another part of town, and there isn’t the same kind of interaction. This has been my first experience where I know the DPs well. I know the costume designers, I know many members of the crew in addition to the above-the-line people.

Salfas: One of the great satisfactions that I experience is an overall sense of community. There’s a connection among, certainly, the key people — the cast, the executive producers, a good number of the writers, some of the production people and post-production people. That’s a very important value in life. In and of itself, it’s very humanizing.

Levy: Bochco encourages us to come down on the stage and observe and learn. I think that’s one of the reasons I was able to make the transition to director — I had the opportunity in my downtime to go and be on the stage and watch. There is that larger sense of community, larger sense of family, and therefore, a greater appreciation and knowledge of filmmaking, of the whole story-telling process. The editors are also invited to the “tone” meetings, which is where the director and writers and Steven discuss the nuances of the script right before shooting. It’s a critical meeting for the editor, because you’re hearing from the writers what their intent is, beyond the words. There’s a lot of subtext in our show, which has to come through the editing. Often what’s being discussed in the dialogue is not the critical action of the scene — and that’s part of what makes the show fun to edit. We have lots of characters, lots of looks, and being part of this tone meeting and part of that process makes us more integral parts of the story-telling.

Salfas: I get great satisfaction from bringing along people who are aspiring to be editors. I have several now working in my editing rooms who are in that position; one of them, Quincy Gunderson, was one of the top feature assistants and was a first on Independence Day and What Dreams May Come. For me, it was incredibly rewarding to be able to bring him on as an editor, to talk to him very specifically about how we solve problems editorially on our show, which I think is very applicable to any kind of film, and then to watch him grow as an editor. We have two assistants on our show this year, and I am working with them in the same way. We have a room set up so that they have access to editing equipment pretty much all day long.

“We have to get used to looking at dailies, evaluating them and getting a story together in a very short amount of time.” – Farrel Levy

Levy: On our show, of the three editors, two — David Crabtree and Etienne DesLauriers — are former assistants. The producers really like working with people that they know, and people who have been on the show. We have four Avids and three assistants, and the assistants do have opportunities to cut scenes. It’s my responsibility to come in and give them guidance on the direction of the scene, the intent, the style of the show, and it gives me great pleasure to nurture people along. Often one of the complaints about the Avid is, how are the assistants going to learn? It’s a valid concern, because many shows have three editors, two assistants and three Avids. The assistants are running back and forth helping the editors and don’t have the time or the equipment with which to start editing. But the Avid can be a great tool when an assistant can make some time to get on it and cut a scene.

Salfas: When we set up our show, I made it very clear that I wanted four Avids, so the assistants would have the opportunity to edit. As we know, one of the downsides to television is the pay, and sometimes we work long hours. I felt that it was important to give the assistants access to equipment and allow them to cut. It’s an opportunity that you don’t really have on features. Usually you have two Avids on a feature, but there’s so much assistant work that the assistants are completely immersed in technical, logistical problems. They don’t have much opportunity to cut. And because the situation is so pressured, you’re usually not going to bring an assistant’s work into a cut. Everything is way too precious — there’s so much money involved. Unless you have an incredibly relaxed relationship with your director, you’re unlikely to bring in a scene that your assistant has cut and say, “Let’s look at this.” I do hear the sort of generic complaint from assistants that they don’t have the opportunities they had when we worked in film. The first feature I worked on as an apprentice was with Paul Hirsch in the early eighties. Paul very kindly took a scene, had it duped in black and white, gave me the dailies and my own set of tracks and let me cut it. And he sat at the KEM and worked on it with me.

Levy: But that’s very unusual. In television, if you have enough people and enough equipment, the Avid can afford assistants much more opportunity to get their hands on things. And because of the amount of work, giving an assistant a scene will, in fact, help me out. I find that by the time I have worked with that assistant over and over, refining the scene, the directors and writers usually like it. And I do like to give the assistants credit.

Salfas: I’ll do that on our show, absolutely.

In our next issue, Levy and Salfas talk about their work as directors and how their editing experiences helped prepare them for the director’s chair.