by Rob Feld

A new animal to the editing world was born––or at least, utilized to its fullest to date––during the shooting in New York City last spring of George Nolfi’s film The Adjustment Bureau, which opens March 4 through Universal Pictures. It doesn’t quite have a name yet—call it on-set editor or reference editor—but it’s a potential boon to continuity and might start appearing regularly in a credit scroll near you.

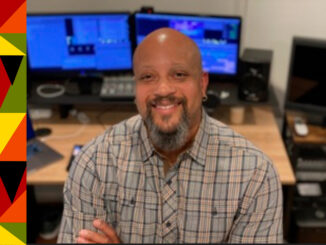

New Guild member Joel Viertel has led many professional lives: as a creative executive at Paramount, talent manager, producer, writer, director and indie film editor. He had met Nolfi during his time at Paramount and ran into him years later in Hollywood, while in prep for a production. Viertel gave Nolfi a scrappy indie film he had produced, the Indie Spirit John Cassavetes Award-winning Conventioneers, which inspired Nolfi to bring Viertel on to produce and edit test scenes for a first film he was considering directing.

Photo by Andy Schwartz. Courtesy of and Copyright 2011 Universal Pictures

When it came time for The Adjustment Bureau to shoot, the idea was hatched to keep Viertel involved by having him edit scenes off the video tap, live on set, strictly for the director’s reference, while picture editor Jay Rabinowitz, A.C.E., was doing the actual cut on his own.

“George is a smart guy,” says Viertel, who also served as co-producer on the project. “This was a big movie to be his first film. To be able to see what you just shot and say, ‘Okay, I can see how this would fit together and I don’t need anything else,’ was very practical. I think he just wanted to make sure he was getting what he wanted to be getting.”

They were unsure if it would be possible to keep up as shooting happened, but Viertel is fast with Final Cut’s hotkeys, so they thought they’d give it a try. A system had to be created, so playback operator Nils Johnson constructed one to handle the two-camera shoot. Johnson would send Viertel the two signals simultaneously, via Ethernet cables. Viertel had two MacBook Pros running Final Cut Pro 7 on a cart––one on top, one on bottom.

“The signals go from the two cameras to the playback operator’s rig via BNC cables, then get re-output to my cart via Ethernet cable,” explains Viertel. “That hits a box on my cart where it’s split back out into two video cables [one BNC for each camera] and one audio cable [RCA]. Those plug into two Canopus converters, which connect to the two computers via FireWire. I just split the audio so it was going to both computers identically. The big computer grabs A camera directly, and pulls in B camera from the little computer––also via Ethernet, a totally separate cable––and now you have both cameras, with audio, in the same timeline.”

As a shot would roll, Viertel would hit “Capture Now” on both computers. Logged in to the second computer from the first computer, he would grab the completed shot, pull it into Final Cut on the first computer and sync the two shots with each other. He’d then put on two filters: one to re-size it, so it could be viewed within the guide, and then a widescreen matte on top. When all was said and done, he had a terrible image off the old-fashioned 35mm video input—maybe with a resolution of 320 by 240—but it was good enough to tell if one shot would cut well into another. He’d sync it all in a timeline and, as a critical mass of shots was reached, would assemble a rough version of the scene.

“Frequently, what would happen, is that we would be shooting one side of the scene––and I would be logging that––but the minute we completed one take of the turnaround, I’d frantically be putting it together to see how it all fit,” Viertel explains. “One of the things it was very useful for––particularly with this movie––was in transitions between different scenes. This was in many ways as useful, if not more useful, than seeing how the scene itself cut together.

“You can usually tell if the scene you’re shooting is going to cut together, unless it’s quite a long, complex bit of business,” he continues. “But whether or not it flows smoothly into the next scene––and arrives smoothly from the previous scene––that’s much tougher to keep your head around, both in terms of the visuals and the characters’ emotional barometers. So, it was very helpful seeing where we were coming from and where we were going.”

He communicated with script supervisor Mary Bailey constantly. “It was a double system on stuff like that,” he says. “Especially if it was checking things from a long time ago, it was a quicker way to get some of that information. At the end of production, Mary said to me, ‘It’s the first time I ever felt like I had a partner in what I was doing.’”

One instance where the system proved particularly useful was a dancing sequence that required a good deal of digital effects work. Actress Emily Blunt had a dance double, and face replacement was being done––for which her face needed to be in the light, oriented the same way as the dance double, Acacia Schachte.

“Emily would do the choreography first, and then Acacia,” recalls Viertel. “I would record it and lay one on top of the other, making one super-saturated and the other completely de-saturated, so we’d be seeing an image of two very similar looking women, doing very similar dance routines. You could then see as they stepped through it that if Emily turned her head to the right and Acacia did the same move, but turned her face to the left, that would be a problem for the effects house later, so we could have them modify this or that as we went, shooting those back-to-back.”

Another particularly useful instance came again with an effects shot, calling for actor Matt Damon to fall down onto a mat. “We needed to get a piece of his body position moving from one place to another, if they wanted to play continuously,” Viertel explains. “We could go over to Matt, show him the out from the take the director wanted to use, and then the in on the next thing so that, in the next setup, for matching purposes we could get from here to there. That’s the kind of thing that would be very hard to see in playback because you’d have to be looking at two shots. Here you could just watch the movie with a black hole in it and say, ‘That’s what we need to fill in.’ That was a very practical application.”

Paul Moore, Eastern Executive Director of the Editors Guild in New York, made a visit to the set and required the company to cover the position under the 700 Agreement. “It is rightfully a Guild position,” he says. “We will probably see this more on jobs with this kind of budget, and increasingly with digital acquisition.

“I think, in a general sense, as the director and producers come back to see a scene they just shot, the advantage of having an on-set editor is that they can put together some scenes they shot earlier in the day and stay pretty tight with the shooting schedule,” Moore continues. “It gives the director a sense of coverage of what he’s done and some of the better select takes––and those notes are transferred over to the picture editor who’s actually editing the job.”

The position became a way into the Editors Guild for Viertel. “I think it was a good thing, because you’re interacting all day with people who are in the IATSE––particularly the playback operator, sound person and script supervisor,” says Viertel. “Down the road, if this becomes a position of any normalcy, it is beneficial for it to already be established as a Guild position because, if anything, not being in the union puts you at a disadvantage in a lot of ways.”

Viertel continues to have his fingers in many pots but says he would absolutely do the job again. “It’s fun,” he says. “It’s a tough job; you’re never not working. As soon as we’re rolling shots, I’m working, and as soon as they call, ‘Cut!’ I’m working harder. There’s a lot of brainpower you have to put into it.”

“One thing an editor really wants is clean entrances and clean exits––or holding at the end of the shot because maybe there’s a dissolve or pre-lap line––just the little things editors want,” he explains.

“As an editor, I know how crazy you can go when you can’t use the shot because they yelled ‘Cut!’ too fast,” Viertel concludes. “This way, you can stop those little problems that drive editors crazy, because you can affect the footage while still on set––before it’s too late. It’s a weird but fun place to be in the process.”