by Bill Desowitz

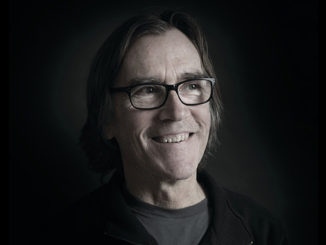

Music Editor Ramiro Belgardt is no stranger to the Star Wars saga. He got in just in time to work on 2005’s Revenge of the Sith, the last of the prequel trilogy, which was supposed to be the end of the franchise. Yet now he’s back for a reboot — the first episode of a Star Wars sequel trilogy with The Force Awakens, which premieres in Los Angeles December 14 through Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, and opens worldwide later that week.

Belgardt’s experience has been a combination of looking forward and backward at the same time, with John Williams scoring his seventh Star Wars movie since 1977 and director J.J. Abrams helming his first. Reportedly, the 49-year-old director was unwilling to commit until Lucasfilm head and producer Kathleen Kennedy hooked him with the question, “Who is Luke Skywalker?”

Thus, the new film is a continued exploration of the tension between what’s good and bad — which is what originally fascinated Star Wars creator George Lucas. “This is a new, energetic reboot,” suggests Belgardt, who’s not quite a stranger to Abrams either, having temp music edited the director’s Super 8 (2011) and the two Star Trek reboots (2009, 2013).

“J.J. is approaching this as a fan of Star Wars, and so he loves it when John quotes musical themes that work from the original,” the music editor explains, taking a break from the film’s post process for this CineMontage interview. “However, both he and John are cautious about wallowing too much in nostalgia; neither of them want to do that. But when it’s appropriate, it totally works. There are moments when you feel you literally could not play anything else. It resonates.”

Indeed, the original Star Wars score has culturally resounded for nearly 40 years, earning Williams his third Oscar out of five, and being placed first on the American Film Institute’s list of the 25 greatest scores of all time. “There aren’t many of them [themes], but there are a few that I think are important and will seem very much a part of the fabric of the piece in a positive and constructive way,” Williams told Vanity Fair earlier this year.

There’s the rousing main title, naturally, along with iconic cues for Luke (brassy, masculine, heroic), Princess Leia and Han Solo (romantic) and The Force (majestic), of course. (See related sidebar, page 57.)

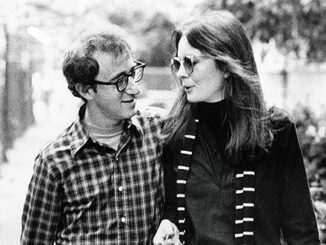

From the start, Lucas’ mandate for Williams was to contrast the futuristic with the familiar, so the composer chose a 19th century-style symphonic score and combined it with echoes from Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Warner Bros.’ swashbucklers of the 1930s. The result was lush, operatic and well- timed retro.

“It’s all a continuation of an initial set of ideas,” continued Williams — who next year will be the first composer to receive the illustrious AFI Life Achievement Award — in the Vanity Fair interview. “It’s a bit like adding paragraphs to a letter that’s been going on for a number of years. Starting with a completely new film, a story that I don’t know, characters that I haven’t met, my whole approach to writing music is completely different — trying to find an identity, trying to find melodic identifications if that’s needed for the characters, and so on.”

The new cast of characters includes Rey (Daisy Ridley), a scavenger from the desert planet of Jakku; Finn (John Boyega), a former Stormtrooper; Poe Dameron (Oscar Isaac), a hotshot X-wing pilot for the Resistance; and Kylo Ren (Adam Driver), commander of the First Order (an Empire splinter group) who’s strong with the Force. Obviously, The Force Awakens also reunites Luke (Mark Hamill), Leia (Carrie Fisher) and Han (Harrison Ford) with a new generation more than 30 years after Return of the Jedi (1983). It’s a continuing struggle between light and dark, good vs. evil.

“I was involved with the temp last December,” Belgardt says. “That was amazing because you had all six Star Wars films and you could put them in where you think themes might go, which filled in gaps nicely, harkening back to the old times. John has embraced some of those old themes in the right spots, and then all this new music is happening over that, so you’re constantly going back and forth between the old and the new.

“The new material is so special,” the music editor continues. “The main characters have brand new thematic material, but it all still feels like Star Wars. You could take any new cue from this movie and play it without picture, and you’d say, ‘Hey, that sounds like Star Wars!’” According to Belgardt, that has to do with the writing, Williams’ orchestration and how it is all recorded by scoring mixer Shawn Murphy.

“The performance we hear in the movie is the performance that was recorded on the Sony Scoring stage,” he explains. “Everyone was in the same room, making music — the way it always used to be. John’s preference is to not use a click track, if possible; the musicians need to hear and feed off of one another to create a performance with personality. Sadly, this is not the way the majority of scores are produced these days. That’s part of what makes music from Star Wars so singular.”

It’s been a stark contrast from the music editor’s experience on Sith a decade ago, which was a wrap-up rather than a new beginning. “There I was — Star Wars, the last one, the turning of Anakin into Vader. I got in there right before it ended. Also, going to London and being at Abbey Road with the London Symphony Orchestra for the first time was something special. John did an amazing thing; it was the beginning of all the things you were going to hear in Episodes IV, V and VI, and he was able to weave in the music so we experience it in its infancy — such as when you see the twins, Luke and Leia, born or witness the genesis of Vader and get to hear the march.”

Sith had the element of foreshadowing the musical shape of things to come. But it also had very original music, involving, for instance, General Grievous. “It was one of the easiest, most loving sessions you could ever have,” Belgardt recalls. “I remember watching George Lucas, looking at the screen and listening to the music. He knew what John would provide, and he was thankful for it. Eventually, we took what we edited at Abbey Road to Skywalker Sound and there were minor picture changes. Then George would have a few music cue changes here and there.”

By contrast, the workflow has been different on The Force Awakens, which has been more in a state of flux. Abrams does a lot more experimenting with the picture editing, by Maryann Brandon, ACE, and Mary Jo Markey, ACE. Scenes have been shifted around to determine what works better structurally and emotionally. Not surprisingly, the opening has changed considerably.

“J.J.’s process is to try everything; his brain seems to work at a million miles a minute,” Belgardt says of his director. “It is amazing to behold. He has so much enthusiasm and inspires real commitment from his team. He surrounds himself with the best people and it makes the process — which can sometimes get exhausting — a complete joy.”

However, he emphasizes, Williams has had to be flexible with his writing approach. “We hold off on certain scenes when we know that there may be a significant re-cut coming,” Belgardt explains. “But at a certain point, something needs to be written. If the scene in question is re-thought again, and it isn’t something that can be fixed editorially, John is game to write it again. In the end, we all want what is best for the picture. So the process of refining will continue, I’m sure, right up until the very, very end.”

As Belgardt tells it, during the composition process, Williams would invite Abrams over to his house to play a couple of the important themes for him on the piano. “I think it would be safe to say it was love at first hearing,” he explains. “As months passed, and we received more of the picture, John would continue exploring new melodic ideas. A few times, we would just end up on the scoring stage and J.J. would hear something for the first time and say, “Are you kidding me? Where did that come from? That’s amazing. That’s my new favorite piece in the picture!”

Was there any thought about updating old themes, given that the original characters are over three decades older? “It’s interesting, because there are quotes of the old themes that will sound very familiar — which is exactly what you would want when you hear to picture,” the music editor responds. “But then, John will take a theme that you thought you knew very well, and re-orchestrate it or use it in a different context. While it has

a familiarity, it is somehow new and revelatory.”

According to Belgardt, the meticulous use of certain themes really ties The Force Awakens to Episodes IV, V and VI of the franchise. “It truly feels like a continuation of the saga after Jedi,” he explains. “Both J.J. and John are so aware of what a powerful tool it is, helping the audience to remember the past while always looking forward.”

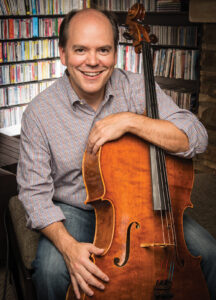

Belgardt, who graduated from the University of Michigan in 1992 with a Bachelor of Music in Cello performance, got his start in the movie industry in 2002 assisting Ken Wannberg, Williams’ longtime music editor, on Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report and Catch Me If You Can. “Ken taught me a lot,” he says. I learned everything about tracking and conforming from him, as well as how to approach a cue that either needs to be expanded, shortened or changed —while always trying to keep its musical integrity intact.”

“Since Ken didn’t really know how to use Sonic or Pro Tools, he would just sit with all of John’s sketches and tell me what bars to cut and where to put them,” Belgardt continues. “It was the best learning experience I could imagine. Most importantly, though, he taught me not to take everything so seriously. Work hard, do your best, but then, for goodness sake, leave the cutting room and get yourself a drink! Both he and John have great discipline.”

Other composers Belgardt has worked with include James Horner (The Missing, 2003), Mark Isham (The Black Dahlia, 2006), Hans Zimmer (The Holiday, 2006), Steve Jablonsky (Transformers, 2007) and Gustavo Dudamel (The Liberator, 2013) — the latter for whom he travelled to Caracas, Venezuela to record the score with the Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra.

But working with Williams has been the most rewarding experience of all for the music editor — experiencing how music can be used and witnessing a greater dynamic on The Force Awakens, in which the composer expands the musical universe while referencing the past.

“It just goes to show the power of John’s music,” Belgardt concludes. “When he does go back to one of the old themes — and it is placed in just the right spot — one cannot imagine a more perfect union of picture and music.”