by Adam Wisniewski

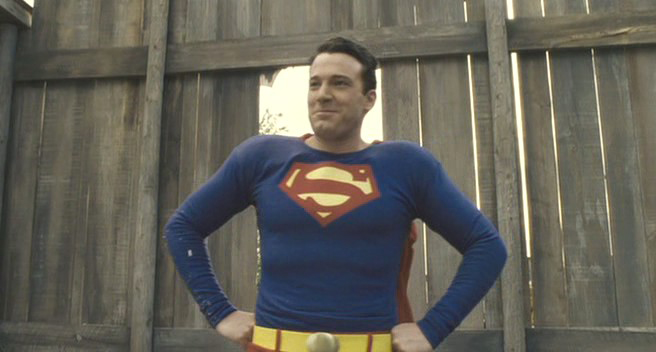

As the editor of Focus Features’ fall release Hollywoodland, Michael Berenbaum can empathize with the plight of the film’s real-life character, George Reeves, and the perils of being typecast. Television’s first Superman, Reeves (played by Ben Affleck) slowly deteriorates throughout the film’s flashbacks as his dreams of becoming a serious actor are crushed by the very public weight of his red cape.

Hollywoodland marks Berenbaum’s long-awaited return to cutting mainstream features after editing Ed, The Wire, and the full run of Sex and the City for television. The NYU film school graduate actually began his career in features as an apprentice on Francis Ford Coppola’s The Cotton Club (1984), an assistant or associate editor on three Coen brothers releases, including Barton Fink (1991), before becoming editor on artist Julian Schnabel’s two films, Basquiat (1996) and Before Night Falls (2000). Then he received the call to edit the Sex pilot.

“I suddenly found myself being thought of as ‘the sitcom guy’ or ‘the TV guy,’ which wasn’t true at all,” he says, six years later. “People tend to think of you as what you’ve done last. I used to be ‘the independent New York film guy’ or ‘the comedy guy.’ You try and do different things so you don’t get caught up in only one aspect of the business.”

But even if Berenbaum had to “suffer” more than half a decade of steady TV work to get back into the movies, the delay had as much to do with his own choices as getting the right call from Hollywood. He is an unabashed, confirmed New Yorker––one who prefers pounding the pavement to navigating freeways and feeds off the compact energy of the city instead of the sprawl of the basin. And New York is still a television town.

“If you’re starting out here [New York], just head out to the film schools and find something to cut. One of those students whose path you cross will be a director someday—and they will hire you.” – Michael Berenbaum

Indeed, it was Berenbaum’s experience as a New York–based editor that drew nearly 50 students and professionals to the Editors Guild offices in TriBeCa in September for a lecture and discussion sponsored by the Manhattan Edit Workshop (MEW), a local educational center specializing in intensive training on both Avid products and Final Cut Pro.

This past summer, Berenbaum served as MEW artist-in-residence for a six-week Art of Editing course, mentoring a class of students and participating with them in a unique project. “The directors of the film I’m finishing now, The Marconi Brothers, are friends with [MEW founder] Josh Apter and they provided footage from the movie for the students to edit,” he says. “It was fun to compare my work with what other people would come up with using the same footage.”

Of the seven student cuts, Berenbaum found that his young editors all kept continuity above the pacing of the scene. “The trap that a lot of people fall into is trying to make the continuity work,” he explains. “You can get away with a tremendous amount of bad continuity as long as you keep moving along. With Sex and the City, it was all about the pacing and the jokes.”

During the hour-long presentation, Berenbaum presented clips from the hit HBO series, as well as Miller’s Crossing (1990) and Barton Fink, pointing out specific challenges or surprises that occurred while completing the projects.

One of his favorite Sex moments came in the show’s final episode, where a montage shows Carrie (Sarah Jessica Parker) taking a clumsy stroll through Paris that ultimately leads her character to consider reuniting with her longtime on-again-off-again paramour, Mr. Big (Chris Noth).

courtesy of Focus Features.

The crew was actually in Paris filming the episode the Sunday before air, Berenbaum recalls. Guest star and love interest Mikhail Baryshnikov had presented the producers with a composition he’d written called “Carrie’s Theme.” They decided to use the song, and when Berenbaum laid the track into his first cut, the tempo of the music coincided nearly perfectly with the characters’ beats on film. The producers mixed the episode on Wednesday, and it went to air the following Sunday.

Working with Joel and Ethan Coen helped the editor appreciate the value of “fortunate accidents.” While in the editing room contemplating the transition of John Turturro’s playwright from New York to Los Angeles in Barton Fink, Berenbaum and the Coens abandoned a lengthy credit sequence depicting Fink’s physical journey westward, deciding instead to jump directly to his arrival at a Los Angeles hotel via a dissolve of the Pacific Ocean violently striking a rock on the beach.

Do a Google search for criticism of the film and you’ll find that has become one of its most cited scenes, all born from a what-if scenario in the cutting room. What the critics don’t know is that this short transition needed a heavy optical effects shot because it was unplanned: Turturro had to be freeze-framed in the center of the image while the spinning fans in the foreground were looped because there wasn’t enough raw footage to complete the dissolve.

Berenbaum later edited Turturro’s film Mac (1992) under a strict mandate from the director to incorporate every goof and accident that occurred on set into the final cut. Judging from the audience questions, many of the attendees were particularly interested in Berenbaum’s advice about surviving in New York’s tight job market. Guild member Oliver Leif, who currently edits television documentaries and HBO’s Real Sports, attended the event because, “I’m interested to hear what an editor can say for an hour about his craft. I’m also looking to move into features, but I’ve only had offers for low-budget films, and I haven’t been able to do it. In New York, there’s a ton of work in cable—but it’s hard to find good work.”

“The trap that a lot of[editors] fall into is trying to make the continuity work, you can get away with a tremendous amount of bad continuity as long as you keep moving along. With Sex and the City, it was all about the pacing and the jokes.” – Michael Berenbaum

For New Yorkers, Berenbaum said it is of utmost importance to meet people in the industry and make connections, because you never know when one of those will pay off with another job. “If you’re starting out here, just head out to the film schools and find something to cut,” the editor suggests. “One of those students whose path you cross will be a director someday—and they will hire you.”

As it turns out, Hollywoodland’s director Allen Coulter is an HBO veteran who worked on Sex and The Sopranos. “The reason friends end up working on shows together is because we like each other,” Berenbaum says, stating the obvious. “And when one of us gets a call, we’ll mention that they should hire this other person, or one of the producers will bring us over with them.”

So what’s with the LA aversion? “I do begrudgingly work in Los Angeles when I must,” Berenbaum admits. “But in 23 years, I have managed to spend only six months there in 1987, and I really didn’t have to go again until 2004.” Although, he adds, most of the people that I’ve worked with over the years have all gone to Los Angeles—people get off the plane there and get hired!”

Near the end of the discussion, a fledgling director questioned the editor about what advice he should keep in mind when he gets into the editing room. Berenbaum let a smile escape, perhaps enjoying the moment to make an editor’s life down the road a little easier. “Don’t get involved in every single cut, because that’s how you lose the forest for the trees,” he offers. “Let the editor do his job and cut it first before you come in. You may see things initially that you won’t like—but you’ll know that it’s the worst it will ever be.”