by Mel Lambert

While the West Coast sound community remains dominated by post facilities owned by film studios and a number of large-scale independents, as was detailed in “Let There Be Sound,” (CineMontage NOV-DEC 12), this follow-up article looks at the East Coast sound contingent, which consists of a handful of post-production facilities that cater to the needs of independent filmmakers and directors based close to the Big Apple, as well as European clients.

Sound One

“Without a doubt, we served a local, East Coast community; what starts in New York normally finishes in New York!” says Jay Rubin, former manager of business development at the now shuttered Sound One, who joined the facility in 1979. At its height, Sound One was arguably the East Coast’s largest post facility, comprising five re-recording stages, two ADR stages, a Foley stage and close to 100 edit suites across six floors of the historic Brill Building in midtown Manhattan.

“Although we opened for business in 1968, it wasn’t until 1981 when [then-president/CEO] Jeremy Koch joined us that we became a successful facility with a large sound effects library,” Rubin continues. “For example, we opened the first 5.1-channel stage in New York City, with six-track dubbers for dialogue, music and effects stems. Prior to Pro Tools, we used NED Synclaviers for sound design and then Sonic Solutions workstations — an industry first.”

As Koch recalled in 1998, “On any given day, upwards of 400 people might be actively involved here in film post production. It has been said that if a bomb were to be dropped on Sound One’s annual Christmas party, the New York film industry would be wiped out, and the industry as a whole severely damaged!”

Avi Laniado, Sound One’s former chief engineer who joined the facility in 1984, says, “Filmmakers now need to accommodate more and more tracks being created by sound designers and dialogue editors. This increased media means that we have to offer more flexibility from editorial to mixing. In order to increase productivity, we developed a way of providing high-speed synchronization between dubbers and the projector to enable fast motion control, including reverse play.”

The first Dolby Surround mix at Sound One was for director Frank Oz’s The Muppets Take Manhattan in 1984 with re-recording mixer Lee Dichter, according to Laniado. “We added Sony digital multi-tracks in the early ‘90s for pre-mixing and finals, locked to a mag track using Adams-Smith time code synchronizers, and then Akai DD-8 disc-based digital recorders, plus DD-1500 16-track systems for recording Foley and ADR,” he adds.

“In 2001, we started to use Pro Tools — initially for editing ADR but, more significantly, for recording — since at that time, the workstation couldn’t emulate the commonly used functions of a tape machine,” Laniado continues. “We were able to achieve this by upgrading to a Soundmaster Atom time code system. That was way before 2005-2006, when Pro Tools added machine control with built-in track arming and punch-in. We then replaced our 10-year-old Akai systems across the entire facility, including the mix stages.”

For Sound One, technology was a natural evolution, Laniado acknowledges, adding, “Filmmakers do not want to think about the process, concentrating instead on creative dimensions, and ways of becoming more efficient.”

(CSS Studios, parent of Sound One, was purchased in September by the Miami-based Empire Investment Holdings, which promptly shut down the New York-based Sound One and laid off the majority of the staff, in order to “consider a variety of strategic options,” according to a company announcement. At press time, no solution had been announced and Sound One remains closed.)

Reeves Sound

Other leading Big Apple facilities include Reeves Sound, which was established in 1933. In 1946, a company offshoot, Reeves Soundcraft Corp., began developing and manufacturing several recording products and other related equipment, including a multi-channel sound system for Cinerama, reportedly the first discrete stereophonic sound system after Disney’s three-track Fantasound optical system.

In 1953, the company won an Academy Award for the development of a process to apply magnetic oxide stripes to film for sound recording and reproduction. Reeves Sound became Reeves Cintel in the early 1970s and transformed into a video production company.

Soundtrack New York

Soundtrack was opened for business in Boston in 1983 by current co-owner Rob Cavicchio, initially for composing and producing jingles for the local advertising community. It then segued into sound post services and music mixing. According to the facility’s executive producer, Christopher Rich, “At one point, Soundtrack was the largest independent owner of large-scale SSL consoles and employed upwards of 50 to 60 mixers, assistants and techs. But by the early ‘90s, the writing was on the wall with the record business going through lots of changes, while escalating rents forced almost half the studios in New York City to close down.

“We built a single, Dolby-certified mixing stage and took a stab at the independent film business,” he continues. “We soon found our footing in what was a very vibrant — and optimistic — independent film climate. The Sundance Festival was a perennial beacon that seemed to dictate our work for half of the year. After a Grand Jury prize win at Sundance for the 1997 film Sunday, and with 60 to 70 independent films and documentaries under our belt, Soundtrack needed more space; hence Soundtrack New York was built in early 2001.”

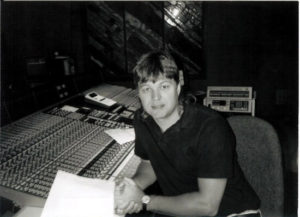

Courtesy of Ken Hahn

Cavicchio hired room designer Jeff Cooper and also film chief of engineering, Bob Chefalas, who also brought with him several seasons of HBO’s Sex and the City. “Bob had been at Todd-A/O and would eventually have a hand in the design of all three stages in New York that have won Academy Awards,” Cavicchio adds. “During the past 10 years, we have added several ADR and dubbing stages, production space and edit suites. We continue to supply sound services to a vibrant and dynamic post community, with a healthy mix of feature and TV work.”

Re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman, CAS, was with Sound One from 1985 until the end of 2003, when he joined Soundtrack; he also worked at New York’s Trans Audio and Reeves Sound. Having used a wide range of tools during his 40-year career, Fleischman put together his top technical developments in sound, and focused on digital technologies. “Digital reverb sounds remarkably realistic and offers a number of creative options,” he says. “My favorites include the Lexicon 224 and sampled convolution plug-ins. I also appreciate the total recall capabilities of digital consoles, including automated panning — which was hard to achieve on analogue mixers — while random-access digital picture offers dramatic time savings, and is highly preferable to a black-and-white dupe! I also rely on DAWs for quick editing fixes during the mix; they allow for the removal of digital clicks and pops from tracks with a high degree of accuracy. With file-based servers, it is far easier to manage original sound elements and masters than with the bulky analogue mag/tape systems.”

C5

Founded in 1989, C5 remains one of the busiest post facilities in New York, with 16 editing suites and a trio of re-recording stages — the latter manned by co-owners Ron Bochar and Paul Hsu; the third co-owner, Phil Stockton, runs a smaller, Pro Tools-based dialogue editing suite. “Originally, the shop was co-owned by myself, Skip Lievsay, Bruce Pross and Phil Stockton,” Bochar recalls. “Bruce left us in 1999 and Skip in 2003, to go freelance. We were renting space at Sound One and leading something of a nomadic life.”

C5’s first premises in Chelsea, on the West Side of Manhattan, offered sufficient space to expand. “We added a mix stage and focused on supplying the needs of the film and TV business centered here in New York,” Bochar says. “In 2004 we relocated to a 15,000-square-foot building where we built a new 4,000-square-foot Foley Stage with high ceilings; we wanted a large, full-featured room that could offer proper services for the local post community.”

After 9/11, the studios and filmmakers started to pull back, and the industry hit an economic slump, according to Bochar, who adds, “When work started to dry up, we scaled back to a 3,500-square-foot operation and, in 2008, relocated to a new space on 25th Street in Chelsea; we still retained the Foley Stage, which remains very busy.”

Courtesy of Soundtrack

In terms of technical developments that have impacted the East Coast post community, Bochar cites five key elements. “The affordability of mixing consoles represents a major breakthrough since now we do not need to spend close to $1 million for a mix system,” the re-recording engineer explains. “Today’s DAW controllers — like the Avid C24 in my room and Paul’s D-Command — let us start mixing in the box from day one. Also, high-speed data networks let us be more efficient, as we access files from a central store, and also share sound effects across our libraries.

“Thirdly, high-capacity hard drives have become very affordable,” he continues. “We use a lot of data storage for our 24-bit/96 kHz files. Mixing in the box has transformed the way we work on the dub stage, and is a huge time saver; there are no more pre-dubs, with everything now staying virtual via DAW plug-ins until print mastering. Finally, digital picture is now very fast-access, and continues to improve in quality. All in all, these new developments mean that we can simultaneously conform a mix, conform the automation and conform the sound.”

“While random-access audio editing had been fairly well accepted, it was not until the picture side moved away from sprockets and embraced the new technology that the industry revolutionized. We now enjoy all-digital, totally automated mixing consoles. While fader automation has been around for many years, the automation of every mixing function presents mixers with a much welcomed freedom.” – Ken Hahn

Digital Cinema

For close to 30 years, Digital Cinema has offered post services for film and TV, originally as Sync Sound. “Our clients include major motion-picture studios, TV networks and many independent production companies,” says co-founder Ken Hahn. “When we first opened, we utilized a proprietary synchronizing and editing system and lots of ingenuity. We have seen audio-for-picture change from strictly analogue to almost completely digital. We were one of the first facilities to exploit disc-based digital audio editing, using systems from AMS, New England Digital and Digidesign. What started as an operation that employed six, grew to well over 40 and, currently, is about half that size.”

In 1997, seeking to integrate disc-based audio editing into the film world, Hahn and his longtime business partner Bill Morino joined with Rick Dior to form Digital Cinema. “Sadly, Rick passed away shortly after the facility opened, but the mixing theatre we constructed for him lives on,” Hahn recalls. “It is New York’s largest feature mixing stage and has played host to major mixers from around the world.” Key post-production projects handled at Digital Cinema include True Grit for Paramount Pictures, Notorious for Fox Searchlight Pictures, The Hours for Paramount Pictures and Borgia for NetFlix.

Hahn’s top five technical developments: “SMPTE/EBU time code and the synchronizer, which enabled tape-to-tape synchronization of all audio and video formats, plus disc-based, random-access picture editing. While random-access audio editing had been fairly well accepted, it was not until the picture side moved away from sprockets and embraced the new technology that the industry revolutionized. Thirdly, we now enjoy all-digital, totally automated mixing consoles. While fader automation has been around for many years, the automation of every mixing function presents mixers with a much welcomed freedom. High speed, digital connection of audio and video across the world means no more waiting for FedEx and, finally, we appreciate the refinement and acceptance of high-definition picture.”

Warner Bros.

Post-Production Services

At the end of 2012, Digital Cinema entered into a relationship with Warner Bros. Post-Production Services regarding the former’s re-recording stage. The update includes refurbishing and re-equipping the mix theatre located on the main floor with a new projection system, Avid Pro Tools rigs, a digital console and a three-way monitoring system. Warner Bros. has also secured 4,000 square feet of picture editorial and sound design suites on the second floor, which will be helmed by industry veteran Lievsay. Additionally, Digital Cinema plans to operate a second mix room, ADR studio and client facilities on the third floor.

Sound Lounge

Sound Lounge’s film and TV post operation opened for business in 2006, when lead mixer Tony Volante moved from Soundtrack to establish an intimate mixing facility that catered to New York filmmakers. His original dubbing stage has since been joined by a second dub stage plus an ADR stage and edit suites. “We look forward to our continued growth and expansion, including breaking ground on a third dubbing stage, an improved ADR stage and four state-of-the-art sound design studios,” says Samara Levenstein, the facility’s executive producer. “We have a small talented staff, as well as close relationships with top freelance sound supervisors. We were the first New York facility to build a stage with multi-system mixing capabilities; now dual-position Avid D-Control consoles are becoming the norm.”

As with its West Coast counterpart, the history of East Coast post-production sound can be told through the story of creative post facilities that made audio developments possible through a combination of tenacity and technical developments.