By Jennifer Walden

For trailblazers, the way forward is not a clear-cut path. Progress requires perseverance because it’s impossible to see what lies ahead — be it good or bad. For those blazing paths in AI, there’s the anticipation of discovery. Where will this road lead? Will it help to accelerate our way of thinking and working? For the film industry specifically, can AI help streamline creativity, help people get from concept to final content more efficiently?

Recently, there’s been much focus on AI for the sound industry, particularly AI sound generators (be it for voice, sound effects, or music). But AI is reshaping the sound industry in other ways, like using procedural audio for sound design — something the game audio industry has been doing for years with great success. And using AI to automate the creation of soundtrack versions (e.g., creating a down-mix from Dolby Atmos to 5.1 or stereo).

Editor Harry B. Miller III has been working professionally in the film industry since 1984, cutting both picture and sound up until 2013 — his last sound editor credit was on “A Good Day to Die Hard” (2013). Throughout his career, he’s experienced technological advancements in both fields, like the industry-altering switch from analog to digital. On “Waterworld” (1995), of the 40 people in the sound department, Miller was the only editor working on a computer-based editing system. “It was all on film. They’d change picture and we’d have to conform the mix to the newest cut, but it was very labor-intensive because you’re working with 2,000-foot reels of mag film, winding them back and forth. You might have four tracks of mag in a synchronizer and you’re winding through trying to see what’s going on. I didn’t miss it when film died. I was totally happy when I started seeing people working on Pro Tools,” he said.

Miller knows that changes in the film industry are inevitable, and adopting new technologies is part of the job. He and visual effects editor Asher L. Pink are co-chairs of the Motion Picture Editors Guild’s Emerging Technology Committee — a team responsible for “keeping apprised of the advances with artificial intelligence and other new technologies, and advising the board and National Executive Director of developments that could impact our members’ work,” according to the Editors Guild site. They recently gave three presentations on “Emerging Technologies” — a general membership presentation, a presentation to sound occupations, and a presentation to picture and other occupations.

Part of the committee’s responsibility is figuring out how AI and machine learning will redefine what an editor does, and what new tasks will be created as other tasks become automated. For example, with dialogue, they noted that any AI-generated voices used as placeholders will need to be replaced in post by an actor because of SAG rules. Someone has to keep track of those temporary AI-generated dialogue lines to ensure that not a single one makes it into the final. “That’s a new task that the dialogue team is going to take on. So even though there may be fewer tasks for actually setting up the recording, there’s this new task of keeping track of the AI voice-generated lines. That’s just an example of a replacement task. One task goes away; another task goes in,” said Pink.

For an ADR recordist/editor, would recording and cutting temporary lines (that would be replaced) be preferable to keeping track of AI-generated dialogue lines in a spreadsheet? What would be more efficient? If working with AI-generated voices for temp dialogue meant working eight-hour days instead of 10-hour days, would this be a task you’d willingly automate?

Miller said, “As a committee, we’re confident that artificial intelligence and emerging technologies can make our lives easier. Some newer plugins that reduce noise in dialogue tracks are amazing, yet they don’t replace a sound editor. An editor still has to cut the dialogue, change parts of performances for clarity, smooth out the edits, and so on. It takes a human to have that judgment and that taste. AI isn’t going to replace film crews. We work for real directors and real producers who have creative intent and creative tastes. That’s not something a computer can judge.”

However, the committee does have concerns about how emerging technology will impact entry-level editors and their level of skill. Pink noted that some elementary tasks — ones delegated to apprentices or editors beginning their careers — could be handled with automation. So instead of having an entry-level editor cutting footsteps in sync to picture, that task could be automated. “That doesn’t mean the work is going to go away. There is still going to be work. But that work is going to filter up to some of the higher function tasks, meaning there’s going to be a larger skill gap that an entry-level editor will need to surpass to make it up to professional. And this goes across the board — for sound and for picture. One of our concerns is that there will be the high skill/knowledge tasks but there won’t necessarily be a ladder to get there,” said Pink.

Consider that those elementary-level tasks, like cutting in footsteps, teach a sound editor how to sync sounds to picture, how to attenuate a sound, use panning, and add processing to sell the idea that a sound is happening and moving within a space. Is proficiency in these basics necessary to achieve mastery later on? How will the use of new technologies change an editor’s skill set?

Miller said, “Our committee researches and advises the board of directors of the Editors Guild on what is coming and what impact that is going to have on our industry. We try to evaluate ‘exposure.’”

They explained that “exposure” is the sum of displacement and augmentation. It’s the degree to which an occupation’s tasks are susceptible to technological change. If a profession is highly “exposed,” it means there’s a new tool that can reduce the time it takes to do a task within that profession. In some cases, high exposure means that the job is in decline.

Miller continued, “These professionals need to learn an additional skill set — learn how to use that new tool — to make themselves marketable. For example, we found that transcribers are going to be highly impacted by AI; they have high exposure. So instead of transcribing, maybe they’re organizing sound and running it through programs that are very good at doing transcripts. On the opposite end, picture editors for scripted projects have low exposure, because when you are answering to another creative, you have to understand what that creative person is looking for and a computer can’t do that.”

Pink added, “We did find that the sound professions have a high rate of exposure, especially the closer they are to dialogue, just because there’s this new tool that can generate very realistic sounding dialogue. We found that sound is definitely easier to create models off of than moving picture.”

STRICTLY PROCEDURAL

Another development for film sound is the use of procedural audio. Pink and Miller see this shift in sound creation as more plausible than AI “text to sound effects” generators. Pink said, “Although generative sound is getting better, anyone who works in sound will attest to the fact that sound editing is not just cutting a sound to picture. It’s choosing the right sound to deliver the right character. That is not something generative audio and a fully automated workflow can do.”

So what is procedural audio? In game sound, procedural audio is an audio system capable of synthesizing sounds in real-time according to a set of programmatic rules, algorithms, and mathematical models such as waveforms, noise, filters, or envelopes to control how the sound changes over time — like changes in pitch, volume, timbre, or rhythm. Historically, procedural audio does not use recorded audio material (it generates the sound), whereas procedural sound design requires an audio file that is then manipulated. (For more detail, check out Dara Crawford’s concise blog post “What is Procedural Audio?” — https://daracrawford.com/audio-blog/what-is-procedural-audio).

Games now employ a combination of both procedural audio (generated sounds) and procedural sound design (pre-existing sounds) to great effect. Looking at “The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom,” during a 2024 GDC talk (Global Digital Cinema is an international company providing cinema solutions and services to distribution and exhibition companies), lead sound engineer Junya Osada explained how the sound team designed “a physics system for sound,” as game director Hidemaro Fujibayashi called it. To very briefly summarize Osada’s explanation, the sound team’s approach mirrored the game physics team’s approach in that both used a rule-based system to control how objects (and sounds) behave within the 3D space in-game.

For example, one sound rule defined how loud a sound could be based on attenuation curves that incorporated acoustic phenomena like sound absorption, deflection, and occlusion. The audio system and the physics system worked together; information from the physics system fed the audio system, which could then automatically calculate changes in volume, and all the necessary processing (filters, reverb, and echo) as defined by the set of rules that all sounds in-game must follow. Additionally, sounds were attached to objects, and when the objects were combined by the player in-game, this resulted in the creation of a unique sound. Ultimately, this “physics system for sound” created an in-game soundscape that mimics the real world. (To learn more, watch the GDC talk “Tunes of the Kingdom: Evolving Physics and Sounds for ‘The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom’” on YouTube: https://youtu.be/N-dPDsL-TrTE?si=tkYQ0ZMIPjQgpdR2&t=2163).

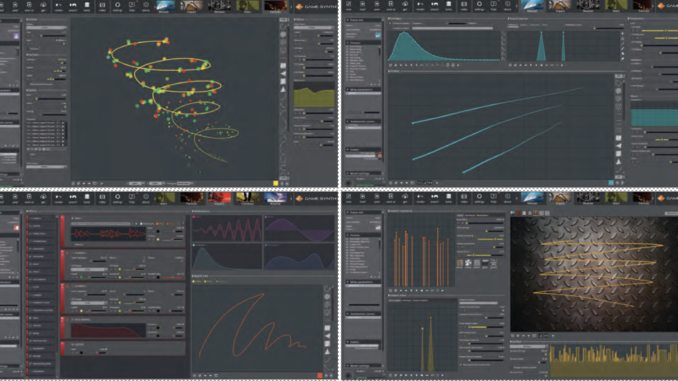

Procedural audio is an invaluable tool for game sound professionals because they’re dealing with non-linear, interactive media. Players can run back and forth across the screen for ten minutes if they choose. Cutting individual sounds for that would defy reason. But is there room for procedural audio/procedural sound design in linear media? Pink believes there is. He said, “You’re stacking effects on effects and tweaking parameters, and it creates sort of a node tree where you can run an audio signal through different sound processing layers to get the sound you want. This is a new avenue for sound editors where they’re not just choosing sounds from a library; they’re using this software to really fine tune bespoke sounds into exactly what they want.”

One example of a procedural audio tool for film sound designers is GameSynth by Tsugi — available for purchase ($390) at tsugi-studio.com. GameSynth is a sound design tool that can be used to create any type of sound — such as impacts, whooshs, particles, footsteps, weather, engines, and more. Sounds can be rendered out and imported into other tools. According to Tsugi’s FAQs, “Many features created for interactive media can also be useful for lin-ear media, such as the automatic creation of sound variations. The video playback feature, which can be synchronized to your drawing on the Sketch Pad, offers an intuitive workflow when designing sound to picture. The GameSynth API allows you to remotely control GameSynth from other creative tools via TCP. It can be used from any tool with scripting capabilities: game middleware, DAWs [like Reaper], graphics packages, and more.”

Also, audio files (samples) can be loaded in GameSynth and used as sound sources or can be analyzed and used to create control signals. Samples can be manipulated using GameSynth’s Particles model (granular synthesizer), or the VoiceFX model for creating vocal effects by changing the processing via a collection of effect racks, for example. According to Tsugi’s FAQs, “The patching environment of the Modular model provides several generators that will take samples as input: the Sample Player, the Granular Player, and the Wavetable. It is also possible to use a sample for the sound source in the Whoosh model or for the impact noise in the Impact model. In addition, features of a sample (amplitude, pitch, noisiness, events…) can be analyzed to provide control curves and logic triggers.”

Pink noted that MPEG’s Emerging Technology Committee often looks at what video game companies are doing because that has had a huge impact on the movie industry. For example, virtual production utilizes game engines — like Unreal Engine 5 — for real-time rendering of backgrounds on Volume stages. “If you’re doing your own research on emerging technologies, the game industry is definitely somewhere to look. Procedural audio engines and synthetic dialogue are the tools that our membership should be learning now. As far as technologies to be looking out for, I would say it’s sound effect recommendation based on machine vision, and automated mixing,” said Pink.

DOWN FOR THE MIX

Downmixing is a time-intensive process that happens after the director approves a final mix. So, for example, a film is mixed natively in Dolby Atmos for theatrical release, and that director-approved mix is then downmixed to 7.1, 5.1, and stereo for delivery to different streaming platforms (which all have different loudness specs) and for localization in different languages. The creative intent of the director must be preserved in the downmixes, which can get quite complicated when taking a wide Atmos mix (that can contain up to 128 channels) and making that translate in a two-track mix.

Scott Levine at Skywalker Sound oversaw the development of a software platform called “Coda,” an automated media processing platform that adapts and versions media to fit pipeline and distribution needs, shortening the deliverable process from weeks to faster than real-time. During a presentation at the Audio Developers Conference in August 2023, Ryan Frias (software engineer from Skywalker Sound) said that Coda was successfully used on over 170 titles, including Disney+ releases like “The Mandalorian,” WandaVision,” “Andor,” and “Moon Knight.”

In Levine’s virtual presentation to SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) members in March 2023, he explained that Coda was developed in conjunction with input from Skywalker Sound creatives. As the software was being developed, it was being tested and evaluated by the sound talent at Skywalker. Coda is an artist-driven tool (not a replacement for artists in any way), so their high standards for excellence in terms of sound quality and preserving the filmmakers’ creative intent required the software development team to design all new signal processing that exceeded the capabilities of current industry tools for downmixing. Instead of taking a static, coefficient-based approach that doesn’t consider content (it’s solely a mathematical calculation), Coda developers wanted to design software that mirrors how an actual re-recording mixer handles down-mixes. Their approach is content-aware. Some of the algorithm training sets for Coda came from Skywalker Sound talent with many years of experience in downmixing. The datasets were based on how they’ve been mixing on the consoles, how they mix different genres, what delivery specs they need to hit, etc.

Coda’s automation engine was designed to be flexible, to handle a huge variety of soundtrack version deliverables for overseas localization. It analyzes the contents of the approved final mix as input, evaluates the specs of the target mix as output, and then dynamically figures out how to stack the processing and manage the generated assets to produce the necessary deliverables. Coda is not a tool for mixing films, but a tool for creating downmixes. Automating the downmixing process for overseas localization is a massive time-saver for re-recording mixers. Certainly, someone will need to oversee the creation of down-mixes made using this tool, making sure the correct deliverables are generated and sent to distributors, but it doesn’t have to be the project’s re-recording mixers necessarily. This could free up time for the re-recording mixers so they can spend more time pre-dubbing or final mixing the next project.

Pink said, “There are going to be changes and there will be a learning curve for almost all of us — for some professions to a greater degree than others. For the people willing to take up the challenge of learning new tasks and skills, they will be fine. That is my prediction. If we step up and learn these tools and combine them with our own creative skills and efforts, we will continue to be valuable assets to any production. We’ll keep creating good motion pictures and television content as a result.”

LEARN TO ADAPT

As co-chairs of the Emerging Technology Committee, Pink and Miller make suggestions to the Editors Guild’s training committee for building a curriculum to address some of the new skills that will need to be learned. However, the rate of change is turbulent and many similar technologies are competing for market share, so it’s challenging to put together a specific list of software applications or tools. Pink said, “Right now, the most future-proof thing anyone can do to stay up to date with emerging technology is learn a programming language. Learn how a program works. You can learn to write formulas in Excel! Just learn how to do some sort of automation so that when you see these types of software enter your workflow, you’ll be able to manipulate them with greater ease. I got started by learning Python; I build my programs in Python. By knowing a programming language, I’m able to adapt that to other programming languages as I need them.”

Miller’s first programming language was dBase, which he learned as a sound editor and used to create a computer-based catalog of the entire sound effects library in the company where he worked. “At that time, everything was on 35mm rolls and the sound effects were listed in printed catalogs. I learned how to program a computer with a database program so any editor or supervisor could go on that computer and do a sound effects search. It helped me to expand my knowledge and expand my employability,” he said.

Miller concludes, “The history of the motion picture industry has been a history of change. Every year there are new technologies, like adding computers to our workflow or new NLE software. There’s always been disruption and the industry has continued. You have to be willing to adapt and learn to keep ahead of it. No, a computer can’t tell what a showrunner or director wants. It is the human editor who does that. What we need as editors is support from directors, producers, and writers to ensure that they get creatively what they are looking for.”

Jennifer Walden is a freelance writer who specializes in post-production technology.