by Laura Almo • portraits by Wm. Stetz

When the curtain rises on “Hollywood’s Biggest Night,” which it will again on Sunday, February 24 this year, the global audience tunes in to watch the Academy Awards live. People are eager to see the stars, the fashion, the elegance, the glitter and the gold in real time.

A big part of this ritual is, of course, to watch the presentation of the awards, from the ceremonial “Here are the nominees for…” to the moment when the presenter says, “And the Oscar goes to…” Be it Best Picture, Actor in a Supporting Role, Costume Design, Sound Mixing, Animated Short — or any of the 24 categories — millions of viewers around the world will simultaneously see the face of each of the nominees in a little box. Viewers see the smiles and the nerves, the exaltation and the reactions, and of course the applause, as each nominee is named and then the winner is announced.

While the television audience is focused on the competition, technical director Kenneth Shapiro is concentrating on making sure those little boxes — and myriad other effects — go off without a hitch.

When everything works perfectly, what goes on behind the scenes at the Oscar ceremony remains invisible to viewers. These seemingly simple yet iconic moments are the work of the effects technical director and, for many Oscar broadcasts over the past three decades (20 to be exact), Shapiro has been responsible for the effects that are so much a part of the Academy Awards show. To put it in perspective, this TD began working on the show in 1990 (the 62nd), the same year Billy Crystal hosted his first Oscar show. (This year is the 91st awards ceremony.)

Shapiro builds the effects that are used throughout the show. Last year, when actresses Jodi Foster and Jennifer Lawrence were on stage presenting the Oscar for Best Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role (to Frances McDormand, in case you forgot), Shapiro was making sure the video effects that he created prior to the show were working and that the camera people had the correct shots and framing. “It’s all about seeing the celebrity faces as big as possible so that the viewer at home can see their reactions to the win or the loss,” he explains.

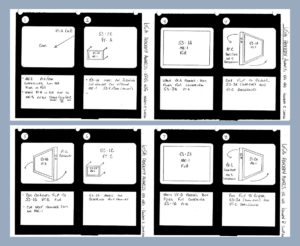

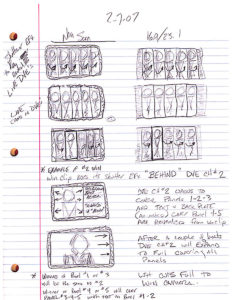

Over the years, as the Oscar shows have become more ambitious, producers and directors want to utilize different shapes and effects. In the past it, was simply squares but more recently it’s become video walls and complex shapes. “For the last two years, the effects design was a parallelogram that was angled,” recounts Shapiro. “And director Glenn Weiss wanted to go from this angled look to a full frame with the box blowing up full-screen. Because of the shape and angle, the cameramen had to frame their shots looser so they wouldn’t cut off the heads.”

Digital video effects (DVE) were always part of the technical director’s job. But as the number of cameras being used grew from 10 to now over 20, plus the addition of more and more LED video walls and other signals needed to be routed and sourced during busy sequences, it became an ever-increasing task for one technical director to stay focused on the main show. “I started to help the main technical director as the complexity of the video signals needed routing and the video effects grew and evolved into another technical directing role,” Shapiro says. “You’re performing similar tasks as the other technical director. You’re sourcing and controlling content, you’re cutting cameras on the air and you’re doing live-editing on the director’s cue.”

At the Academy Awards, there are now three technical directors working in different zones: the screens, the effects and the main show. Working in collaboration, the trio takes the creative ideas from the show’s director and executes them in a one-time live situation. Eric Becker, the main show technical director, is responsible for all the camera cutting, keying and playback elements, while John Pritchett, the screens technical director, focuses on all the feeds going to the video walls, set monitors and projection feeds. For his part, Shapiro, who has worked the show the longest, creates the multi-camera digital video effects boxes mostly used for the nominee categories or special sequences.

Oscar TDs are a close-knit group. For many years, Shapiro worked the show with John B. Field (the primary technical director for the main show), Rick Edwards and Allan Wells, whose fortes became coordinating the screen feeds going out to the stage. More recently, Becker, Pritchett and Iqbal Hans have come into the fold.

A Chicago native, Shapiro grew up in the television and live TV world. His father was a technical supervisor for WBBM, the CBS-owned-and-operated station in Chicago. In high school, he was involved in the school radio station, where he was a production manager and had his own show.

After graduating, he moved to Colorado to pursue his dream of becoming a professional skier. When he realized that wasn’t in the cards, he returned to Illinois and enrolled at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. During his first year, Shapiro started working weekends for his father’s company. It was after learning how to use a new slow-motion instant replay machine that Shapiro started traveling to work on sports events and variety television.

Shapiro worked on the national broadcasts of the World Football League and met the crew, including Gene Crowe, who went on to become one of the top technical directors in Los Angeles. “It was a tremendous group of people who were the cutting edge of freelance live television in the mid-’70s, and that gave me a lot of opportunity,” he recalls.

While in California for a game, he visited another show at Pepperdine University in Malibu and struck up a conversation with the crew working in the VTE (Video Tape Enterprises) broadcast truck. When the technical director learned that Shapiro knew how to operate and maintain the new slow-motion/instant replay disc, he asked if he wanted a job. “And it was like, BAM — I’m there,” Shapiro remembers. “I’m done with school. I’m moving to California. And there was no turning back.”

Shapiro traveled to work on sports and specials. In 1984, he came off the road and took a studio job (as a videotape operator/editor) at Entertainment Tonight (1981-present). It was an opportunity to learn new equipment — and also a turning point in his career.

“I had a fascination to learn the new Ampex ADO Digital Effects System (the newest DVE device at the time) because ET had such high demand for constant effects,” he relates. “They wanted a lot of pizzazz. They wanted lots of effects transitions. Different DVE boxes were being utilized for live shows and it was all about what it can do, how quickly can we get it done, and what’s new/different about it?” As part of the Miss Universe team, Shapiro would create nearly 200 effects during both pre-production editing and the live show using different DVE equipment.

Any chance Shapiro got, he would learn the new equipment/switchers and video effect boxes. He devised the “page turn” effect, which was used for many years on ET and was key to his effects training. When he started working on awards shows and specials (Miss Universe Pageant, Emmy Awards, Golden Globe Awards, American Music Awards, etc.), he pretty quickly showed producers/directors that he had the chops to deliver the types of effects they were envisioning.

Oscar Bound

In 1990, Shapiro’s technical prowess landed him an opportunity to work on the Oscars. The director was Jeff Margolis, with whom Shapiro had worked on the AMA Awards. “He saw that I could make that box perform, and when he had the opportunity to bring me on to the Oscars, he jumped at it.”

Tasked with trying to bring new visual effects to the Oscar broadcast, the TD remembers, “When I got to the Oscars, it was another giant leap. The director wanted to explore the next level of video effects as well as incorporate elements of the production design into the look of the video effects.”

Since he first began working on the Oscars in the ’90s, shows have gotten bigger and more complex, costs have increased and digital technologies have changed the way he works. Shapiro observes that building the effects and doing setup for the show takes less time than in the analog days. “The effects are one of first things we rehearse on camera,” he explains. “The technical setup takes a couple of days. That time used to be consumed with installing all the equipment and getting all the sourcing worked out and routed correctly. Digital technology changed everything. The technical setup now goes much faster.

“The engineering team for the Oscars is amazing,” he continues. “There’s a lot of planning and attention to detail. There’s a giant infrastructure for the show and the effects are just one element.”

But some things haven’t changed too much, according to the technical director, who stresses that rehearsal is still crucial to test everything. So is the chance to run through the show with the camera people using stand-ins for the nominees, and to double-check that the right name comes up with the right face.

From Shapiro’s vantage point, live shows like the Oscars are about anticipating the points of disaster. For example, a sequence starts and one of the nominees is missing. This is something that has happened numerous times over the years. “Maybe the nominee is a no-show or in the bathroom,” he posits. “The bottom line is that they are not on camera. What do we do? Do we drop all the effects? Do we move on and stay with the package?”

He recalled a near disaster with a nominee effect at one of the Oscar telecasts on which he worked. Shapiro had built a complex 3D “slab” video effect using multiple videotape machines, electronic graphics, numerous keys and still-store slides that on-cue would flip around to reveal the live-nominee camera in the audience before flipping around to the next nominee clip.

“When we started into the effect sequence, one of the camera people got on the PL [private line intercom] and said that the nominee was not in his seat,” he reveals. “At that time, we only had no-show photos of nominees we knew were not coming to the show. I realized that we did not have a photo of the missing nominee to substitute in place of the live camera. I had planned for a ‘bailout’ possibility but had not rehearsed the procedure. It made my heart triple in speed to try to figure out how to get around it.” Even though Shapiro was manually sourcing the inputs during the sequence, at the last second he was able to jump to the next videotape, bypass the live camera and advance to the next key frame to get back into the sequence.

“Now we try to make sure that we’ve anticipated every problem,” he adds. “We have a photo backup just in case they’re supposed to be there but didn’t show up. We try to have backup plans for everything.”

For Shapiro, a self-proclaimed adrenaline junkie, being a technical director for live TV suits him well. Whether it is making sure all the cameras have their shots framed correctly or that the wrong camera is not cut to, he knows that the stakes are high when there is only one chance to do things perfectly.

“Technical directors are expected to be 100 percent all the time,” Shapiro maintains. “There’s no ‘Fix-It-in-Post.’ The amount of adrenaline that gets pumped as we go on air is a feeling I’ve always loved. I love that high-stress, short-term pressure, when you’ve got one chance to do it right.

“It’s just like skiing down a mountain,” he continues, harkening back to his original career dream. “You don’t want to make any mistakes. You don’t want to hit a tree. You want to get all the way down and feel great about it.”

In the early-to-mid-2000s, Shapiro directed 19 episodes of the sitcom Everyone Loves Raymond (1996-2005). Since then he has also gone on to direct an extensive array of televised classical music and operas, as well as the documentary Great Voices Sing John Denver (2013), in which opera singers perform songs from the singer/songwriter’s catalogue. “After that, it was nice for me to be able to come back into the live television world,” he offers.

As for his best day at the Academy Awards, Shapiro says it was doing the Oscars with Crystal the first time they both worked on the show. “Not only is Billy a great comedian, he is also an extraordinary entertainer,” the TD recounts. “He ended his opening monologue with a humorous short medley about the Best Picture nominees. And I was tasked with creating video effects during his medley performance.”

Before Crystal’s rehearsal, he would briefly meet with the host to describe the director’s framing of the camera and where the effects were entering and exiting the picture around him. “Billy was very interested in where his eye line should be,” Shapiro says. “Then we would record a rehearsal and I would follow the script and take my cues from him. After each rehearsal, we would watch the playback and make adjustments to the effects to coincide with his movements. By the third time through, the performance and effects blended perfectly. It’s a thrill when something complicated appears natural and gets the desired reaction from the audience.”

It has been nearly 30 years since Shapiro’s first Academy Awards. To what does this multi-hyphenate attribute his longevity working with the Oscars? “Luck,” he replies. “That and my continued excitement about the job at hand. It’s the passion, the rush and a great group of people. There’s a lot of clout to the show and I’m humbled to have been a part of it for so many years.”