compiled by Michael Kunkes

It is perhaps coincidence that in 2009, a year that, by even the most generous critics’ standards, has been a pretty dodgy one for cinema, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has upped the Oscar ante by deciding last year to increase the number of best picture nominees from five to ten. AMPAS President Sid Ganis calls the decision a return to the Academy’s “earlier roots,” and indeed, ten best picture nominees haven’t been seen since the 1943 awards year. A cynic might say that this also doubles the opportunities for studios to promote, market and advertise. It also makes one wonder longingly what might have been, in more recent years past, when films that should have made the cut did not.

While one can argue about what this increase really accomplishes, it does open the field to a wider range of contenders. And who better to give their sometimes strong opinions on the Oscar-worthiness of last year’s releases than Editors Guild story analysts? Editors Guild Magazine asked several of them a simple question: “In a perfect world, what would be the Best Picture of 2009?” Their answers ranged from actual nominees to personal favorites. For more than 75 years, story analysts have been the gatekeepers of the motion picture process. This time, however, they get the last word rather than the first…in a parallel world, at least.

I’d call Avatar “wildly innovative,” Precious “gut-wrenchingly courageous” and The Hurt Locker “absolutely engrossing,” but when asked to comment on the “best” movie of the year, I thought of the simple, everyman stories. Not those with flying creatures and an alien mineral known as unobtainium, nor those with horrifying, abusive flashbacks or rigged explosives in foreign lands. Instead, I thought of those stories driven by everyday desires and insights, as well as arguably average characters––movies that still manage to make a fresh impact on the screen.

Stories such as these, in the unique voice of the writer and made with the vision of the filmmaker, are heightened by humor and pathos and honesty. They emerge feeling like a rare, true glimpse into humanity. The best movies for me are like opening a book to a passage from Salinger, Bellow or Updike, and affirming that, yes, seen through incisive eyes and articulate narrative, life is still as one remembers it––altogether daunting, hilarious, painful, risky, heart-breaking and absolutely lovely. For me, then, Up in the Air and The Hangover tie for best movie. Real people saying real things in an original way, which caught me by surprise and moved me to a place I hadn’t predicted.

Brian Brightly

A review of Three Idiots that I recently read said, “Whoever would have thought that comedy and suicide would go so well together?” Oddly enough, I suspect that almost anyone who has ever seen a commercial Indian film wouldn’t be surprised to find slapstick and tragedy––and a few very catchy songs––rubbing elbows in the same film. As you may have already guessed, in my perfect world, this film would be handed the gold on Oscar night. It’s a sometimes broadly comic, sometimes deeply moving indictment of an education system that values teaching students how to pass a test more than its does teaching them how to think for themselves. It is also a surprisingly effective romantic comedy.

While I suppose I could waste space trying to justify my fantasy Oscar winner by making it sound far more pretentious and/or meaningful than it really is, the truth is that I chose Three Idiots because I was moved by its message: Follow your own dreams rather than try to make come true the dreams that others have dreamed for you. And it made the two nine- or ten-year-old boys sitting in front me so excited that they couldn’t stop talking about it to their mother on the way out of the theatre. If you ask me, that is quite an achievement for a film that is totally dependent on simple human interactions to keep its audience in their seats.

John Byers

Larry Gopnick, the protagonist of A Serious Man, is a physics professor whose endless, complicated “proofs” are useless when his life starts unraveling. Like a rooftop antenna in need of adjustment, Larry is desperate to lock in on a clear signal and learn why terrible things befall him. Gopnick seeks answers from three rabbis, and doesn’t find much he can use. One sees God’s presence in a parking lot; another tells the story of a dentist who discovers a message on a patient’s teeth and finds peace only when he stops obsessing over why it’s been shown to him; and the third refuses to see him at all.

In the words of one of its characters, A Serious Man asks us to “accept mystery,” lest we end up like Larry’s brother Arthur, who’d be well adjusted if only he could drain his obsession to create a “Theory of Everything” as easily as he does the cyst on his neck. When the third rabbi quotes the Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love” to Larry’s son Danny, he repeats the film’s opening and closing lines: “When the truth is found to be lies and all the hope within you dies…you better find somebody to love.” The advice, read one way, is to find meaning in something simple, fundamental and human.

A Serious Man is about what happens when we look for rationale in things that are beyond our control. I’ve heard it called depressing (among other things, its final moments depict Danny in a tornado’s path). But tragedy, like one’s opinion of the film, depends on interpretation. And this is the movie’s brilliance: At the end of the Bible’s Book of Job, God appears as a whirlwind and restores Job to health…so you never know. It’s best not to ask.

Zach Chassler

In a year of it-may-as-well-be-CGI-animated overkill, it’s still easy to make my pick for best picture, and not because I have been a Disney story analyst. Everyone knows Pixar and Disney are worlds apart when it comes to process and creativity, so the “Oh, Disney” dismissal does not apply.

When I wrote coverage on-lot, I had a post-it reminder on the computer, reminding me to ask myself the single question: “Is it good?” And by “good,” I didn’t mean goody-goody, well-crafted or “cool,” a word that became hateful in the mid-‘90s along with “kick-ass.” I meant, “What’s the point? What does it add to the human experience?”

The answer to that question was always a binary number, either one or zero; good or not good, there or not there. So I relied on my “good” rule for “pass” or “recommend” and UP is my “recommend” this year because it has the courage to place age and aging at the center of a story in an industry generally inclined to pander to its mall-based idea of young people.

Beneath the structure, the wit and the brilliant color palette, there is nothing cute about this artful film. Recently, my wife Clare and I spent time in Milan, where we made an appointment to see Da Vinci’s The Last Supper. Going in, I thought I knew the painting, but nothing––all of the study, all of the talk––prepared me for seeing the real thing. The real thing takes you beyond what you think you know. It takes you to that place within yourself where emotion and understanding inform one another. I don’t have to think there; I know. And that’s how I know UP is the best film of the year—an exquisite accomplishment that says, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” to quote William Faulkner.

Peter Flood

I usually am not on the bandwagon with the most “in” popular movies, and I was resistant to join in the praise machine for Avatar. Then, I saw the movie and became another believer. At the risk of sounding trite and unoriginal, it simply is the best movie I’ve seen in years. This incredibly beautiful, harmonious world––where every living creature is respected and appreciated––spoke to something in my core that believes this is the way life should be.

The power of Avatar is that it has spoken on a visceral level to a huge body of moviegoers. The elements of the film span the spectrum of what each person feels is necessary for the film to be a success for them. For some, it is an elemental action story that keeps them on the edge of their seats. For others, it is the romantic element, and for yet others, it is the spiritual aspects of the storyline. What is unique about the film is that James Cameron has seamlessly woven all of these elements into a movie that compels the audience to embrace all of the story and character arcs.

Few notice that the storyline sometimes goes over the top. Fewer still notice that the characters may wander a bit from the credible. What everyone sees are characters who engage the emotions of the viewer, and a storyline that evolves into epic proportions that allows you to leave the theater feeling far better than when you walked in.

Avatar is a magnificent piece of filmmaking. From inception through execution, it is a living force that allows the audience to share in the magic of what a movie should be.

Judi French

This year, several films impacted me, and I did not care if it was the script, the talent, the filmmaking or the editing which touched me. They were, in no particular order, 500 Days of Summer, Crazy Heart, Up in the Air and The Blind Side. However, there were two very different films that I found to be extraordinary and compelling.

When I first saw Inglourious Basterds, I was taken aback at the chutzpah of Quentin Tarantino’s unabashed attempt at offering yet another view of World War II, the SS and the Holocaust––yet I am surprised to say that the film stands on its own. “Tarantino takes on the Holocaust” was how the rumors began, even before many had read the screenplay. Then, to create a Jewish/American scalping squad made many people uncomfortable, dumbfounded and amazed that this script could ever get made. The outcome, whether happy or horrified, is that the filmmaker was able to create an old-fashioned epic drama that I believe is an example of storytelling at its best.

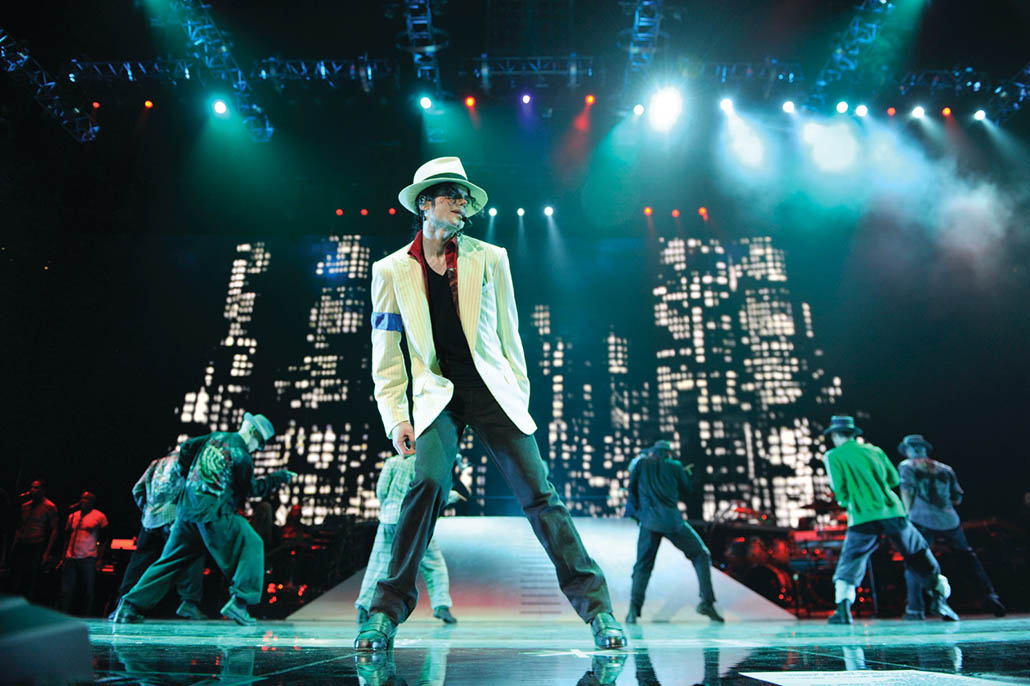

The unscripted This Is It will, I believe, remain the definitive autobiography of Michael Jackson. It demonstrates that through extraordinary directing and film editing––created merely to document the “making of” what would have been a monumental example of creative genius––actually stands as an impactful, emotional and compelling story. I am in awe of what Kenny Ortega and the film and music editors were able to extrapolate from the footage, which for me exemplified the creative life that was the genius of Michael Jackson. The film also provided a look back to The Jackson 5 and moved in and out of the 40-some years of this performer’s career, enabling us to better understand the pain and compelling storyline of Jackson’s life in intimate detail. Here is an example of a non-scripted film that told a unique, complete and emotional story containing every element that is needed to make a viable feature film screenplay.

Joy Hurwitz

While I’m bored with the trend in moviemaking towards extravagant special effects at the cost of story and characterization, I chose Avatar for reasons other than spectacle as the top film of 2009. The movie shocked me with its subversiveness. Where else in the contemporary political climate would we see the equivalent of American military members––our own heroes––cast as the villains, and defeated by foreigners who are “the good guys?” The film asks Americans to look at what other cultures must feel about our occupation of their land and use of their resources, such as oil.

To paraphrase a line in the movie, “We [humans] make an enemy out of other cultures so that we can use force to get our hands on their precious resources.” The parallels to our country’s dealings with the Middle East and other regions are clear. Avatar blends this with a powerful environmental message. Incidentally, the heartbreaking bulldozer scene happens to resemble a number in Michael Jackson’s This Is It, also from 2009. For me, a film that wins best picture has to have timeless meaning as well as timely appeal, and that’s why I think Avatar deserves to be the Best Picture of 2009.

Robin Jones

The Best Picture money’s on Avatar, of course, and the hipper choice would be The Hurt Locker or District 9, but I’ve got to go with Up in the Air. It delivers both the glossy wind-up of an expert wish-fulfillment fantasy, and the darkly satisfying thud of truth when the bubble of all that dreamy glamour bursts.

This story, about a guy who flies around the country firing people for a living, is a high-wire act of sorts, as it balances on the edge of where comedy turns to tragedy and vice versa. The movie––which does a lot of shrewd, hard work to seem breezy-easy in its delivery––is about going in two directions at once. You want to love Ryan Bingham because George Clooney’s playing him, but he’s actually kind of despicable, in a marvelously charismatic way. And you want everything to turn out okay for the people in the story, even when everything in the movie’s telling you that “okay” isn’t really an option in the end.

While some may find the movie too glib for its own good, I applaud its anti-feel-good spirit. For once, the hero’s eventual redemption doesn’t earn him happiness––a rare move for such a “Hollywood” picture. Meanwhile, there are minutes of pure rom-com bliss scattered throughout Up in the Air. The scenes between Clooney and the lovely Vera Farmiga are as witty as a vintage screwball comedy’s. When these two are on screen together, the movie’s feet don’t touch the ground. But the counterpoint that brings it back to earth has a devastating accuracy and punch. There’s one heartrending shot here of an office, nearly denuded of desks and activity, inhabited only by the few walking wounded left in a local workforce. It’s the most eloquent big-screen portrait of America in 2009 that I’ve seen outside of a newspaper’s front page.

Billy Mernit

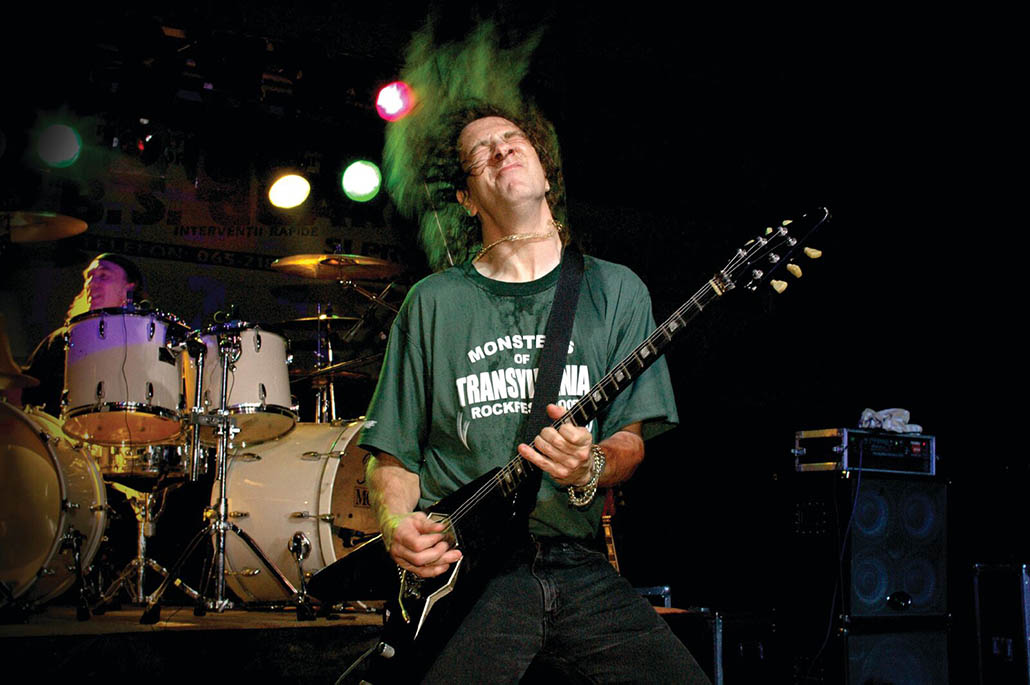

Lips, the hapless, hirsute leader of a never-giving-up band of 50-something rockers that’s stuck on a European tour from hell, waxes philosophical as the guys miss another train to another existential gig: “It’s a good thing we got those sleeping bags,” he says, adding later, “Things went dramatically wrong, but at least there was a tour for things to go wrong on.”

If like me, you haven’t had much use for heavy metal in your life aside from repeat viewings of This Is Spinal Tap, you might not be inclined to see Anvil! The Story of Anvil. But despite their hair, leather and ear-splitting pyrotechnics, Lips and his lifetime comrade-in-arms, drummer Robb, are really two nice Jewish boys from Toronto. And their dedication to their music in the face of decades of also-ran misery made this documentary a wholly universal, hilarious and nearly heartbreaking exploration of the nature of success. After seeing it, you wonder: Are we not Anvil, or rather, have we not been them at some point in our creative lives?

When are we too old to keep doing what we love to do? “Time doesn’t move backwards,” Lips sagely notes. Indeed. It takes great insight and lack of illusion to see your second act turning point when it’s upon you, and realize it’s time to move into your third. In this regard, Anvil! brings an optimistic message to the longevity-challenged among us still tilling the fields of creativity. The band’s perilously unlikely climactic turnaround at a do-or-die concert in Japan would be unbelievable if it weren’t true. We can’t all be so fortunate, but it’s good to have inspiring role models, however unlikely. So excuse me now, but I’ve got the first draft of a screenplay to get back to. For even if it goes dramatically wrong, at least there will have been a draft to go wrong with.

Billy Mernit

My choice for Best Picture is The Hurt Locker, not only because it is riveting and beautifully crafted, but also because it is an important film. I believe that an Oscar-winning film should be important. It should have resonance.

I can’t think of a film from the past year that has more resonance than The Hurt Locker. It embodies the essence of a decade of wars (Iraq, Afghanistan) that have played out, for soldiers and civilians both, like a game of Russian roulette. It transports you into the shoes of Sergeants James and Sanborn and Specialist Eldridge, for whom the possibility of instant obliteration is part of the daily routine, as is the pain of watching others suffer the same fate––like the luckless Iraqi man literally locked into an explosive harness with the timer counting down his remaining seconds on earth.

The impact of the film is that much greater because, though we know it is fiction, we also know it is fact. Just as we know that, though James, Sanborn and Eldridge are fictional characters, they personify iconic human reactions to war: James, the war lover; Sanborn, the skilled professional just trying to make it through; and Eldridge, consumed by the terrifying randomness with which death is meted out. These memes are brought into sharp focus by director Kathryn Bigelow’s exceptional attention to visual detail––a gimpy cat limping across a devastated, trash-strewn street; a man furtively humping an oversized TV around a corner; and those ever-present watchers…are they innocent or just waiting for the right moment to blow everyone to hell?

The Vietnam War had its signature films, movies that captured the essence of its particular brand of insanity. The Hurt Locker does that for the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts, and it does so with extraordinary power and finesse.

Rachel Singer

Certainly the 2009 film that stuck with me the most was A Serious Man, a movie that I might consider a “perfect world” best picture if for no other reason than the ambiguous power of its haunting final image of a tornado encroaching on the Minneapolis-St. Paul suburb where beleaguered Jewish protagonist, Larry Gopnik, has endured innumerable Job-like trials and tribulations. Whatever one’s faith, or lack thereof, this movie probes some of life’s biggest issues––the challenges of marriage and family-raising; the temptation of wrongdoing; mortality––without providing easy answers.

A cuckold, ripped-off by his pubescent daughter, oblivious to his son’s pot habit and indebtedness to a neighborhood bully, seduced by the sexy siren next door and lured by a student’s bribe, Larry, strikingly portrayed by Michael Stulhbarg, wears a face of bewilderment and mounting despair as a trio of rabbis are unable or unwilling to provide the answers he seeks to the meaning of it all. When he finally does act, accepting the bribe to pay the fees of a lawyer representing his strung-out savant pedophile brother, God seems to reward his unrighteousness with bum medical news as the tornado gathers on the horizon.

A Serious Man, set in the turbulent 1960s, is beautifully directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, working with their frequent collaborators. Often darkly funny, the film’s misanthropic spirit is offset by the poignancy of Larry’s plight. Though Jewish, he seems an “everyman,” calling out to a God who may or may not exist. Surely the aridity of the film’s suburban landscape reflects the bleak lot of a troubled soul grappling with life’s uncertainty. Thoughtful, evocative and unsettling, A Serious Man deservedly made Oscar’s final ten.

Ben Vanaman

As much as I’d like to rave about an overlooked underdog, I have to go with the standout favorite here, Avatar. Okay, I’m a cynic and, at first, I was pretty skeptical about it. No doubt the script for Avatar read well, with the movie’s exhilarating sense of adventure and intense conflict. But could I lose myself in a movie that was about, as my teenage daughter’s friend snarkily put it, “weird blue people?” But it was the rare film that the whole family wanted to see, even my video-game obsessed son. So we went—and we were hooked, from the dramatic opening to the explosive finale. It was awesome, spellbinding and lots of other superlatives story analysts rarely get to use.

The 3-D was a big part of it, of course. It grabbed me and threw me right into the action. The well-crafted story had all the right ingredients: suspense and excitement, heart-tugging twists and a theme that echoes our own misguided foreign incursions in a way that continues to enrage conservative blowhards. The way the story took place in parallel realities—the “real” clinical world of the laboratory pod that was Jake Sully’s gateway to the lush, ethereal world of the Na’vi—added narrative dimension like the 3-D added visual depth. The visual effects? There’s nothing I can add that hasn’t been said. Real meshed seamlessly with unreal until you could almost say, “What visual effects?”

James Cameron and crew have made the movie to beat. And kudos to his co-producer Jon Landau (once my roommate at USC; nice guy, even if he tended to leave his radio alarm on really loud). There are other deserving films that left a lasting impression. But I’ll be rooting for Avatar Oscar night. Go “weird blue people!”

Rick Weaver