by David Timoner

In the fall of 1992, I was a wide-eyed freshman at Yale. I signed up for Intro to Film Studies, hoping that the class would be one of my favorites. I loved movies, and it seemed like a good way to satisfy some humanities requirements. After several weeks of class, I was disappointed with it, however. The professor’s area of expertise was early American film and he spent the first several sessions tediously breaking down The Life of an American Fireman and The Life of a Cowboy, two crudely made short silent films. They may have been two of the first American film narratives ever made, but I found them utterly boring.

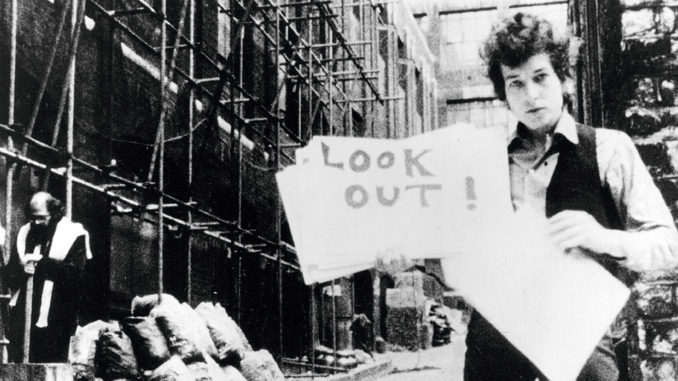

Finally, we started a unit on documentaries, the first of which was DA Pennebaker’s 1967 film Dont Look Back. In the opening scene, a young Bob Dylan stands in an alley, holding and dropping cue cards corresponding to his single, “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” Beat poet Allen Ginsberg wanders around in the background looking like a lost Hassidic scholar. I was already a big Dylan fan, but the raw absurdity of the clip stuck with me.

It was experimental and non-narrative––a proto-music video made some 20 years before the format was established. As a member of the original MTV generation (back when the network actually played music videos), I recognized the motif from an early ‘90s INXS video that was clearly paying homage to Dylan. I went straight to the video store after class, rented the film and returned to my dorm room, where I pulled my chair up close to my crummy 12-inch TV and pressed play.

In the spring of 1965, Dylan was a rising star of American folk music. At just 23, he had already been crowned “the voice of a generation” for his politically charged classics The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Blowin’ in the Wind. Dylan was starting to experiment with electrified folk-rock and lyrically moving away from overtly political subject matter.

Grounding these vérité snippets are Dylan’s solo tour performances, the meaning of his lyrics seemingly deepened by the stark black-and-white photography.

It was at this pivotal time that Dylan arrived in England for a three-week tour. Pennebaker was with him, letting his handheld 16mm camera generously roll while Dylan traveled the country, performing to sold-out concert halls, toying with members of the press, and jamming late into the night with Donovan and Joan Baez, among others.

The film presents the musician as a complex figure, alternating between approachable and kind as he gently defends his artistic integrity to a gaggle of star-struck schoolgirls, and downright cruel when he stubbornly punishes a reporter by refusing to define himself or his music. Like its subject, the film resists convention. Gone are the constructs of narrative filmmaking. No omniscient voice of God telling you what to think. No three-act narrative structure confining the plot.

Pennebaker, who also edited the film, simply got out of the way and let Dylan be Dylan, relying on his camera to capture that essence. The action unfolds at the rhythm of life. Seemingly mundane moments like Dylan window shopping for guitars, or pounding out lyrics on a typewriter while Joan Baez––his then girlfriend––sings softly in the background, make the viewer feel as if he or she is right there in the scene. More than anything, Dont Look Back demonstrates that when it comes to non-fiction filmmaking, aside from compelling subject matter, access is key.

Pennebaker had an unprecedented level of access to Dylan and the inner workings of his tour. Grounding these vérité snippets are Dylan’s solo tour performances, the meaning of his lyrics seemingly deepened by the stark black-and-white photography of him alone onstage in vast, dark halls, illuminated by a single spotlight. The last scene of the film has Dylan leaving a sold-out concert at Royal Albert Hall––and for the first time in the film, the wisecracking songwriter poet is speechless and seems genuinely humbled by his own experience.

As the film ended, and my dusk-filled dorm room came back into my peripheral vision, I was struck. I pressed rewind and watched the film again. It was the most intimate portrait of an artist at the peak of his creativity that I had ever witnessed. I was at once inspired and exhilarated–– and I knew what I wanted to do with my life.

In the ensuing years, I learned how to edit and began making documentaries. When I moved to Los Angeles, my sister and I began documenting bands and musicians. In DIG!, our first feature documentary, we had a compelling subject, total access, and ultimately a critically acclaimed film. For me, it all began that rainy night in New Haven, when I said to myself, “I want to make a film like that.”