by Cynthia Wang

Richard Chew, ACE, who won an Academy Award for Best Short Documentary for “The Redwoods” (1967) and a Best Film Editing Oscar with Paul Hirsch, ACE, and Marcia Lucas, ACE, for “Star Wars: A New Hope” (1977), didn’t plan on a career in the movies, but the medium proved perfect for the stories he seemed destined to tell.

Growing up in Los Angeles as the son of Chinese immigrants, Chew prided himself on being a good student while also admiring his brothers, who were drafted into the military during World War II. He, too, would join the Navy before earning his bachelor’s degree in philosophy from UCLA. He then headed to Harvard University to pursue law with an interest in social justice. But one trip to a New York City cinema “changed my mind about how I wanted to go forward in life,” he said.

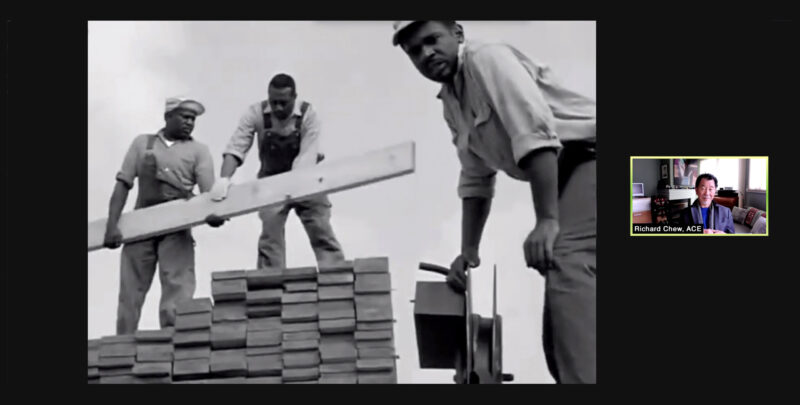

That film was Michael Roemer’s “Nothing But A Man” (1964), an independent drama about Black identity starring Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln. “I grew up in a neighborhood that was very mixed racially, so I had friends who were Black, Latino and Japanese,” Chew said, “but I never saw that represented in movies in a way that was as powerful as this.”

With his political consciousness awakening during the civil rights movement, Chew saw how Roemer’s pointed portrayal of discrimination affected him and the audience. “I think it spoke to me as an artist, or spoke to my artistic instincts,” Chew said, “and that I wanted to be able to tell stories that move people and change their mind about things.”

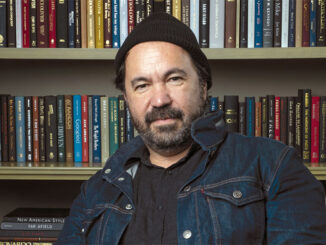

Chew would go on to co-edit Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Conversation” (1974) and Milos Forman’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975), and craft indelible scenes in films as varied as Paul Brickman’s “Risky Business” (1983) and Emilio Estevez’s “The Public” (2018). He became a film pioneer, even if he never set out to be one. “I think I was seen as kind of like a golden boy, being an oddity because I was, like, the only one as far as I knew, the first and only Asian American film editor,” he said. Perhaps, he added, those who hired him simply thought, “‘Let’s give him a shot.’”

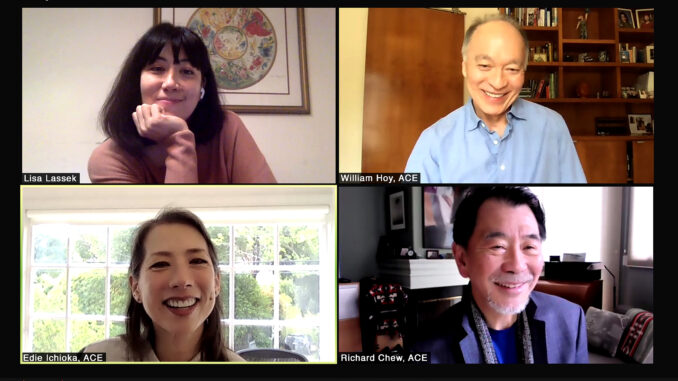

Asian American picture editors Chew, Lisa Lassek and William Hoy, ACE, discussed their influences, their careers and the cultural experiences that shaped them during a “Celebrating Asian Pacific Heritage Month” Zoom seminar hosted by Edie Ichioka, ACE, on May 15 and presented by MPEG’s Pan Pacific Asian Steering Committee. The panel also deconstructed examples of their work and offered advice to members in the well-received session.

Nena Erb, ACE, co-chair of PPASC along with Rosanne Tan, ACE, helped coordinate the panel. She joined the committee a few years ago “because, for most of my career, I’ve been the only Asian person on the show,” she said. “So my motivation was to help bring awareness and visibility to other AAPI members as well as create a community for us.”

It’s a community that Lassek, whose 20-year career has spanned television series such as “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” and “Community” to films such as “The Avengers” (2012), has come to value. When Ichioka asked if she had ever experienced any bias in the cutting room, Lassek, who described her heritage as half Korean, admitted, “It’s an interesting question because I never know if I’m being discriminated against because I’m a woman or because I’m Asian.” Although Lassek said she used to say she was lucky in her career to have avoided uncomfortable situations, “all these things that have come up recently have you thinking of things in a new light,” she conceded. “I feel like it’s great that we are so much more aware of it now, unlike myself when I was coming up…. For me, it was something that was never talked about.”

Yet in moving up the ranks, learning AVID on the job while cutting industrials and promos, working on “super-low-budget features” and documentaries, Lassek developed not only her editing skills but her confidence in her scene suggestions, sound choices, and storyboarding ideas. “Directors hire us for that point of view,” she said, “that we’re not just slavishly trying to do what he wanted, but we bring our own storytelling ideas into the mix.”

In Lassek’s featured clip from writer-director Drew Goddard’s neo-noir thriller “Bad Times at the El Royale” (2018), Cynthia Erivo’s singer Darlene Sweet is practicing “You Can’t Hurry Love” in a hotel room, occasionally clapping and pacing to mask the sound of Jeff Bridges’s Father Daniels searching for a bag of money hidden under the floorboards. Through a one-way mirror and from a secret corridor, Dakota Johnson’s armed vigilante Emily Summerspring looks and listens for anything amiss but becomes enraptured by Sweet’s voice.

The tension shown on screen, scored just by Erivo’s acapella performance, “was just an amazing thing to work on,” Lassek said, “because it’s such a weird scene for the whole movie to put on the brakes for this pure song.”

For action film editor Hoy, working in the abstract has brought him acclaim for “Patriot Games” (1992), “I, Robot” (2004), “300” (2006), “Dawn of the Planet of the Apes” (2014) and “War for the Planet of the Apes” (2017), the latter two winning Satellite Awards for Best Film Editing along with Stan Salfas, ACE.

Hoy explained the difficulty and labor involved in CGI-heavy films such as the “Planet of the Apes” franchise by showing an early cut of actors as apes in motion-capture suits, reacting to a soundstage environment, then showing the same scene with effects added. To appease studio executives, test audiences and the director, Hoy would attend visual effects meetings and other planning sessions just to stay on top of each element. “There’s so many other things happening, but you have to sit in that room,” he said, “because if I’m not there, it comes back that, ‘Well, that’s not what [the director] wants,’ so now we’ve wasted all that time.”

Yet the rewards are worth it for Hoy, a Chinese Canadian American from Vancouver who always wanted to be in the creative arts. He followed his older sister Maysie Hoy, ACE, to Los Angeles, when she had started her acting career in Robert Altman’s “McCabe & Mrs. Miller” (1971). Altman ran his company like a repertory company, so “if you weren’t acting in his film, then you were doing research or you were in the editing room, and Maysie was,” Hoy explained. “I would go there for lunch and the post-production sound supervisor one day said, ‘Hey, you want to come work for us?’”

After 50 years in filmmaking, Hoy, like his pal Chew, said the welcome in which he was received into the business has continued, and any feeling of being singled out because of his heritage has come outside the cutting room. “Even when I go and interview with directors,” he said, “I don’t ever come out of there thinking, ‘Well, I didn’t get that job because they looked at me and I was Chinese, or I was Asian.’ I just hope that’s so and I’m thankful for it.”

All on the panel agree that more representation can only be better for the industry. At the end of the session, Hoy offered a “special shout-out” to Chew. “For me personally, it was like, ‘How can I do this?’ I had Richard,” Hoy said. “He was always there and he gave me encouragement to be an editor and be a working editor in the feature-film industry. Thank you, Richard.”

Cynthia Wang, a longtime entertainment journalist, was a former reporter and editor at People and a features editor at TV Week Australia. She has also contributed to publications such as Empire and lectures at the Medill-Northwestern Journalism Institute. Contact her at cynthia@cynthiawangmedia.com.