by Kevin Lewis

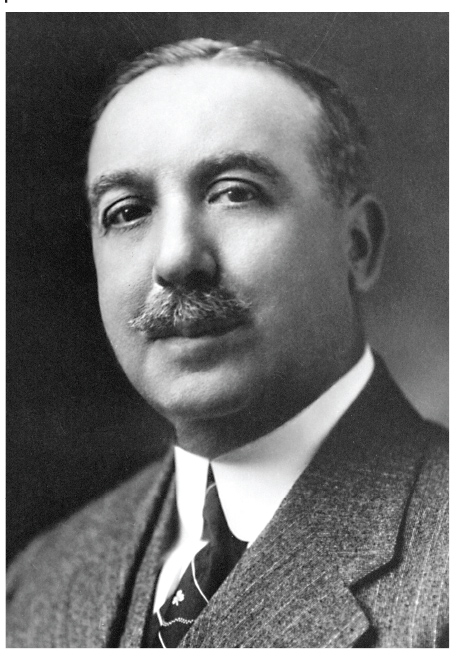

Though not well known, Edwin S. Porter should be regarded as the father of film editing because the basic principles of the craft did not exist before he directed and edited The Life of an American Fireman, which was released 105 years ago in January 1903. What is more remarkable is that Porter was a technician and film executive in the embryonic film industry and was not innately an artist.

Perhaps that is why D.W. Griffith is generally acknowledged as the touchstone for film editing. But it wasn’t until 1908 that Griffith began advancing the art of the motion picture through artistic narrative derived from his prolific reading of such 19th-century novelists as Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. In writing serialized novels, both British novelists developed cross-cutting and parallel storylines in literature––just as Porter and later Griffith did with motion pictures. In fact, Porter actually gave Griffith his start in films when he hired him as an actor in Rescued from an Eagle’s Nest (1907).

Porter, who was born in 1870 and died in 1941, had a succession of jobs before he worked for Raff and Gammon, the company that marketed the Edison Vitascope in 1896. He was involved in the first public screening of projected motion pictures in America at Koster & Bial’s Music Hall in New York in 1896. Two years later, Porter was manufacturing projectors and cameras on his own, and was making actuality and news films that he sold to Edison. When his manufacturing plant burned down in 1900, he became an Edison employee in charge of production at Edison’s studio on East 21st Street in Manhattan. Most of the Edison films were directed and photographed by Porter.

Experimenting with trick and special effects photography, including double exposures, stop-motion and split screens, Porter imitated the films of the French magician-cum-filmmaker Georges Méliès. The Méliès films were immensely popular worldwide and gave Americans their first glimpse of filmed narrative. Méliès made well over 500 short films from 1896 to 1913 in France, mostly utilizing stop-motion photography to provide the trick effects in such fantasies as Cinderella (1899) and A Trip to the Moon (1902).

But the Méliès films are essentially tableaus in which each action is completed in long shot against a stage setting. Porter imitated this in his own films for Edison. However, he never had the artistic instinct to develop stories or direct actors. In many respects, he was closer to a documentary filmmaker than a narrative director, as his later career would prove.

As scholar Charles Musser, the leading authority on Porter, points out, the director/editor had made earlier films that advanced the principle of parallel action, such as The Execution of Czolgosz with Panorama of Auburn Prison (1901), in which the audience is allowed to see a staged re-enactment of the execution in the electric chair of President William McKinley’s assassin. Porter directed scenes in the prison cell and then the execution chamber. “Film thus allowed the spectator to be in two places simultaneously or to see the event from two perspectives,” writes Musser in The Emergence of Cinema. “It was this insight that underlay many of the innovations in cinematic representation that followed.”

Lewis Jacobs, in The Rise of the American Film, describes the genesis of the groundbreaking The Life of an American Fireman: When Porter was searching for stories to film in the Edison vault, according to Jacobs, he found many actuality films of fire department activities. Knowing their commercial appeal, he decided to construct a film around that premise. But the isolated scenes needed the organization of a story. “Porter therefore concocted a scheme that was as startling as it was different: a mother and child were to be caught in a burning building and rescued at the last moment by the fire department,” Jacob writes.

Karel Reisz, one of the premier film editors as well as directors, wrote in The Technique of Film Editing why this was also significant. Porter superseded the director as the author of a film by constructing a film from previously shot material from other filmmakers, according to Reisz. Porter also proved that “the meaning of a shot was not necessarily self-contained but could be modified by joining the shot to others,” Reisz states.

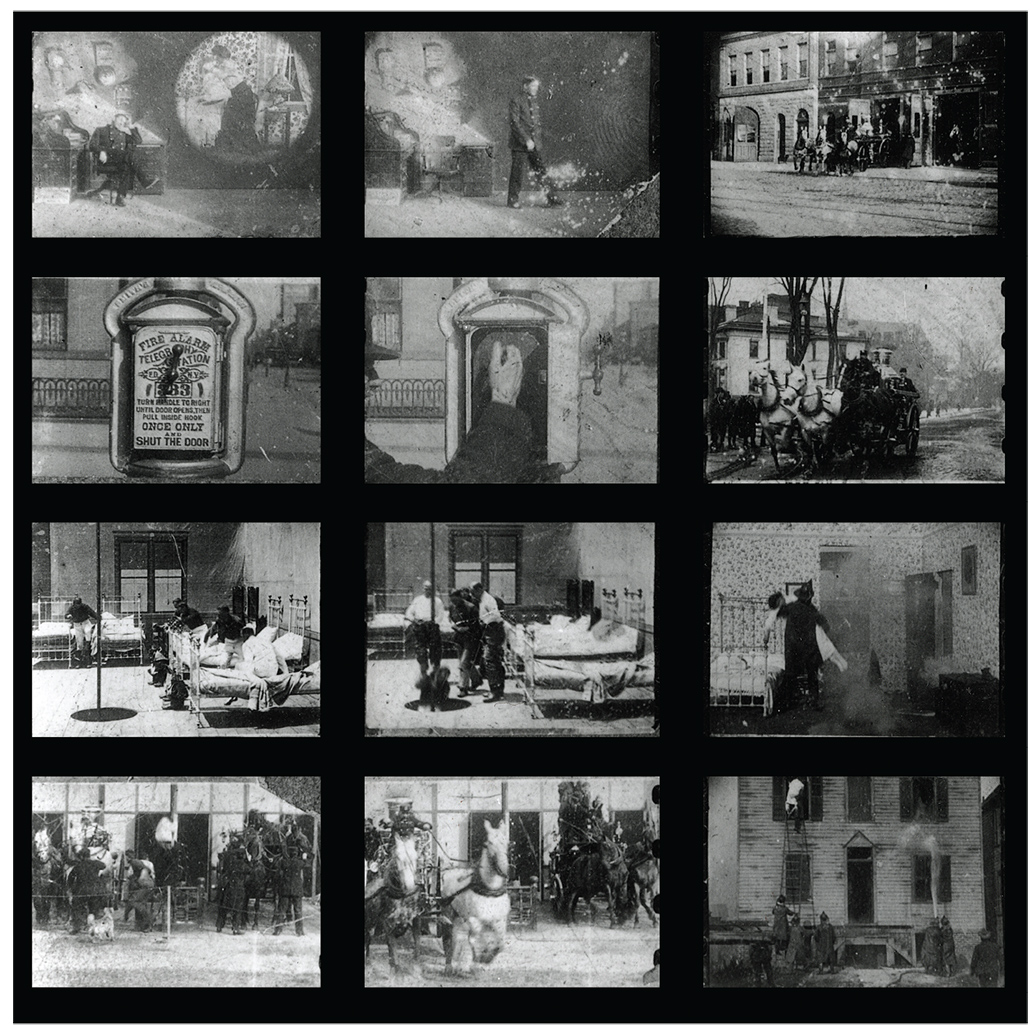

The Life of an American Fireman has nine shots in three stages. The film begins in the station house with a sleeping fireman dreaming of his family at home, which is conveyed by a balloon image over his head. A burning building is then shown, followed by the firemen and horses rushing to the fire. We then see the interior of the burning room with a mother and child trying to escape. The outside of the building is shown with the fireman climbing in the window. The fireman is then shown inside the building rescuing the mother. Next, the exterior is shown with the fireman and mother outside the burning building. Then he returns to rescue the child.

“By constructing the film in this way, Porter was able to present a long, physically complicated incident without resorting to the jerky, one-point-at-a-time continuity of a Méliès film,” Reisz writes. Fluency in screen narrative was gained, but this parallel action, relates Reisz, gave the director “an almost limitless freedom of movement since he can split up the action into small, manageable units. In the climax…Porter combined the two hitherto separate styles of filmmaking: He joined an actuality shot to a staged studio shot without apparently breaking the thread of the action.”

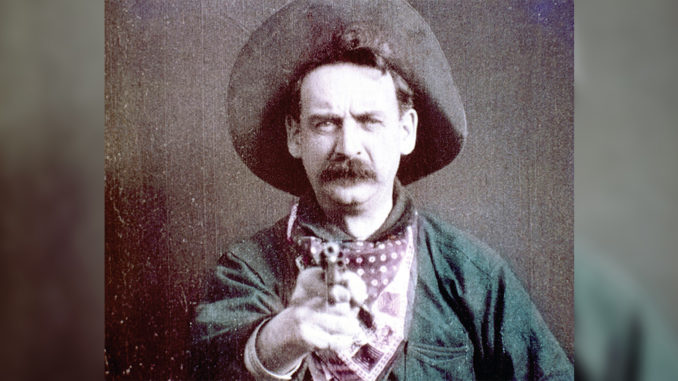

By the end of the year, in December 1903 when Porter’s The Great Train Robbery was released, he was a master of narrative. The Great Train Robbery is still justly famous, admired and widely shown––and its final image of George Barnes as the train robber shooting the audience is an endlessly reproduced cinematic icon. In almost documentary mode, the complete steps of a train robbery are shown in detailed, separate and often concurrent scenes. Shots of different locations whiz by in rapid order in this roughly 12-minute film: The robbers forcing the operator to set the signal block to stop the train at an unplanned station, and then binding and gagging him; the robbers crouched behind the water tower; the boarding of the stalled train; the cold-blooded murder of some of the passengers; a dance hall dive where a tenderfoot is forced to dance amid gunshots at his feet; the posse pursuing the robbers; and the shooting of the robbers.

The final shot is a nihilistic non sequitur worthy of a Luis Buñuel or Jean-Luc Godard: For no logical reason, one of the train robbers shoots point blank into the camera. It was a super finish that rivals any trick shot by Méliès. Interestingly, the Edison Film Catalogue of 1903 films informs exhibitors that the scene of the cowboy shooting the audience can be used as either the opening or the closing of the film!

One can only wonder if Porter’s intention was to shoot his cinematic mentor. He never told…