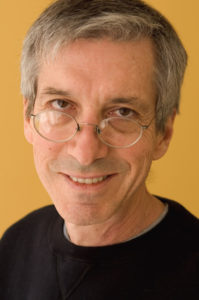

by Michael Kunkes

It might come as a surprise to a lot of people in the industry to learn that the job of the story analyst goes way beyond reading a script and writing coverage for executives. In truth, the analysts involvement has been reaching beyond that narrow definition for some time now.

“Were a pretty well-educated, intelligent bunch of people,” says analyst Calvin Yocum, who once served as secretary/treasurer of Local 854, the story analysts IATSE affiliation before they became a part of Local 700 at the turn of the century. He has been working at 20th Century Fox since 1997 and spent seven years at Columbia before that.

We are always trying to improve a script and focus it from one draft to the next, Yocum says, explaining the story analysts task. We will compare new drafts to previous ones so that we know all the actual changes. We might provide them as a list, or a synopsis in which changes are italicized to provide a legal record of what a screenwriter has done for his money this time around.

A far more important part of that process is to evaluate whether changes work and which ones still need to be made, according to Yocum. Oftentimes, projects will lose their focus over the course of the process and that’s where we can provide a really valuable perspective because we’re the ones who can remember all the way back to draft three, which may ultimately have been the best version.

Yocum recalls reading the script for Men In Black during the 1990s. Ed Solomon, the screenwriter, couldn’t quite nail the story, and that was something I brought up repeatedly in coverage of successive drafts, he says. The studio brought in another writer, David Koepp, who improved the story but imparted a much darker tonality on the piece. And much of the humor that appealed to us in the first place was lost.

We got so wrapped up in what was working in Koepp’s material, and not working in Solomon’s, that we lost sight of the whole gestalt which was that this was supposed to be a fun movie, he continues. I kept hammering away at that, and eventually the studio rehired Solomon, who kept a lot of Koepp’s story elements, but brought back his own twist on the characterizations and the comedy. And it made around a half-billion dollars.

Sometimes, we’ll even end up working on scripts that we initially passed on, but because we were the original analysts when the projects came through the door, we remain the persons on those projects throughout the development process, reading successive drafts, says Jana Carole, who has been a story analyst with Columbia Pictures for 18 years. Whether it’s five or 45 drafts, we will analyze the differences between the various drafts down to the smallest detail and provide input as to whether a project is moving forwards or backwards.

There is also a potentially large employment base in the legal community, where story analysts are used by studios as expert witnesses but they’re also highly qualified to do legal research in intellectual property cases in the entertainment industry, says the Garby Leon, most recently an analyst at Fox who also has held executive positions at Silver Pictures (where he developed The Matrix), Fox Family Film Division and Mosaic Media Group. We’ve even had analysts fly to foreign countries to testify.

I’ve prepared materials for some Writers Guild arbitrations, admits Guy Phillippi, an independent analyst who has worked at various times for Warner Bros., Disney, Universal and Fox. He recalls the time when Sondra Locke was given a deal at Warners after her well-publicized break-up with Clint Eastwood. Because she wasn’t getting many scripts made, she claimed that the deal was set up as an appeasement so that she wouldn’t sue Eastwood, he relates. She also claimed that the story analysts were told to pass on all of her scripts. Well, no one at a studio would ever tell you that.

“Why would you turn someone down just because she had a bad relationship with a star?” he asks rhetorically. Besides, a studio would make a deal with the devil if someone came in with a good script.

Deconstructive Analysis

Fellow analyst David Bruskin, who represents the story analyst classification on the Editors Guilds Board of Directors, provides another perspective on how the job of the old-fashioned title of reader has evolved into a scientific process. If you look at old coverage from studio files, the synopsis used to be way, way longer, he explains. Given that movies are different, analysts have had to become very deconstructionist in terms of what is working and what isn’t. A screenplay can be compared to a car: Everyone knows what it’s supposed to do, but until you look under the hood and take the engine apart, you don’t know how it works. Current coverage involves that kind of analytical ability, according to Bruskin. Older movies relied more on the gut instinct of the producers and studio heads, he says. Now it relies more on what’s making the money this weekend.

The goal of deconstructive analysis is not to dumb down a script. Sometimes something is written so well it can obfuscate the flaws, Bruskin explains. When I worked on Stephen Frears Hero (1992), the screenplay was by David Webb Peoples, a fine writer. Frank Price, the head of Columbia at the time and a former analyst himself, said something wasn’t working for him, but he couldn’t figure out what it was. I happened to put my finger on it for him and that launched my career into a very fertile period. But I was only able to do that by completely taking it apart to see what really made it tick.

Studios have been known to buy material off a pitch or a terrific concept alone, adds Carole. We can recommend a concept, saying that the execution is not very good, but that the seed of the idea is really fabulous and the studio might nevertheless want to consider developing this further.

When I read 50 First Dates, it was a written as a vehicle for two completely different actors, had simpler plot devices, and was set in Seattle, not Hawaii, she continues. But it had a great dramatic concept and a lot of heart, and changed for the better on its way to becoming an Adam Sandler vehicle. An idea is almost incorruptible as long as you have people working on it who really appreciate it.

Analysts are also called upon to work in acquisitions, usually for smaller producers and distributors, where an analyst will be called on to watch a movie thats already made. It’s a little more difficult to write a synopsis, because you can’t go back and refer to a script, says Phillippi. In those cases, you almost become a movie reviewer.

Yocum speculates on another way that analysts could get more notice. I wish we had more of a sliding pay scale based on the contributions we really make, he says. We can make a recommendation that will eventually earn millions for a studio. Yet we don’t get studio heads coming over, giving us a pat on the back and saying, Hey, that was a really great piece of coverage you wrote yesterday.

Story analysts’ uniquely intuitive skills can also be utilized to cover screenings of foreign films for remakes, chart comedy beats, report on pitch meetings, match a writer to a project, write treatment synopses, create any number of specialized breakdowns, and do translations from foreign languages. But still, the bottom line is finding that great story with the kernel of genius.

My job is all about storytelling; whether it’s movies or books or kids telling stories around a campfire, it’s all the same, says Yocum philosophically. The rules of story have been the same since the collective consciousness appeared out of the darkness, and I just try and apply those universal rules to whatever is put in front of me.

The process of good storytelling hasn’t really changed in the 80 years that story analysts have been employed by studios, says Carole. Some of the technical dynamics are different, the budgets are exceedingly different, and the complexities of an international market are also different. All these things have a trickle-down effect on how we will read any given script on a given day. But it still doesn’t change what we are looking for: a great, solid story.

There should never be a formula; when you read a script, you bring your whole experience to it, Leon opines. In a strange way, all of us are experts; we all have PhDs in entertainment, and it’s rather extraordinary.

Pressure on Signatories

So-called entertainment degrees or not, story analysts are certainly feeling their oats these days. It wasn’t always the case. When they were folded into the Editors Guild from their previous roost at Local 854 in 2000, they were a dispirited group of studio employees and independents without much faith in what their union could do for them. That was a sad commentary on a group of individuals who have been serving studios and independent producers for over 80 years, have been organized for some 50 years, and are widely regarded as the gatekeepers of Hollywood though they receive no screen credit and are rarely given their choice of projects. Now, backed by the strength of the Editors Guild, the 141 union story analysts have embarked on a campaign to raise awareness of their important role in the industry, hopefully right a few wrongs, and find new ways to expand their membership.

Over the past year, the Guild has embarked on a campaign to organize non-signatory companies that are under no obligation to hire union analysts, as well as bring to task signatories to the union basic agreement. The effort has been spearheaded by analyst Leon, with help from and Bruskin, support from the Guild Board and oversight by Assistant Executive Director Cathy Repola.

I was floored when I realized that there were numerous companies among the hundreds of signatories who were undoubtedly using readers while not employing them under the agreement, so I decided to pursue this situation something the old Local wasn’t even interested in finding out about, recalls Leon, who played an activist role in the changeover from Local 854 to Local 700.

A number of companies were even claiming they had no story analysts at all, he continues. Under that scenario, are we supposed to believe that ICM just sends a script over to the studio and they shoot it Leon feels that when a company says that, they are either subcontracting the work or they are getting it done for free. I realized that we needed to rock that boat, he says. By enforcing the contract, we were looking at a tremendous opportunity to expand our membership.

The Guild has tested the waters and filed some 20 separate grievances, but the process is expected to take some time. However, according to Leon, the crucial time is now. If we do really well with a few of these situations, it will send a message to dozens of other companies that they should skip a useless battle and abide by the contract, he says. I think we are in a strong position and I am cautiously optimistic, but it’s going to be tough.

Nonetheless, the board is totally justified in taking these actions, which could bring in hundreds of new members, he continues. We are on the threshold of a very historic revolution about how story analysts are hired in the industry and how they are treated. Nobody has ever gone to bat for us before like the Guild has, and we are all very happy and excited about it.