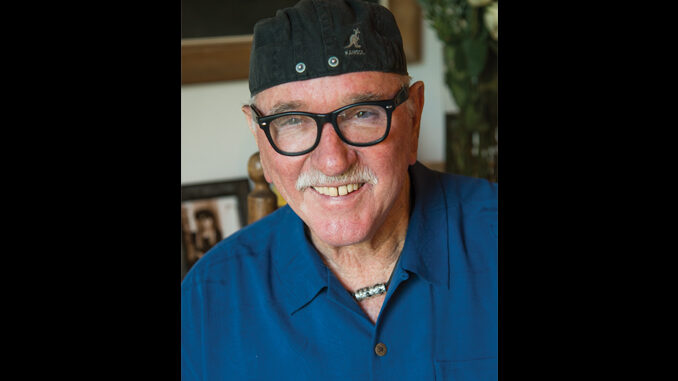

by Laura Almo • portraits by Wm. Stetz

Richard Halsey, A.C.E., lives by three rules: Be organized, listen to your intuition and always tell the truth. These are rules that the editor applies to his work, as well as to his life. Of course, Halsey says, it’s not always easy.

The Los Angeles native grew up within a stone’s throw of Hollywood. Attending Bancroft Junior High, Halsey often thumbed a ride home from school with James Moore, head of TV Editorial at Warner Bros. With little idea of what he wanted to do, Halsey took Moore up on his offer to “drop by editorial” at the studio.

From humble beginnings in the mailroom, Halsey became a messenger, biking around the Warner lot delivering film for all of the TV shows. Even before working editorial, Halsey learned how to sync dailies. When Moore moved on to 20th Century-Fox, he brought Halsey along and got him a job in the music department. After a stint in the army, Halsey returned to Fox, first in the coding room and then as an assistant editor on the series Peyton Place (1964-69), where he was promoted to editor during the final season, cutting 15 episodes.

Halsey’s early years at the studios was training ground for a lifetime of editing such films as Rocky (1976), for which he shared Oscar, ACE Eddie and BAFTA awards with Scott Conrad, A.C.E.; Beaches (1988), American Gigolo (1980), Edward Scissorhands (1990), Sister Act (1992) and many films with Paul Mazursky.

Upon being notified that he would receive a Career Achievement Award from the American Cinema Editors, Halsey was thrilled. “I told [ACE and Editors Guild President] Alan Heim that this was practically the best phone call I’ve ever received,” he says. “I was so honored. In many ways, it means more than the Oscar because you’re being honored by your peers.” Halsey was honored at the 64th ACE Eddie Awards at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills on February 7.

Halsey’s wife Colleen, who is also an editor, observes, “He has a beautiful rhythm and grace with his editing.” The Halseys have collaborated on and off for 29 years. Their first film together was Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986), on which Colleen was an apprentice. “He has a great instinct for editing; he can look at something and see where the flaw is,” says Colleen.

A tough guy whose soft side has won over audiences far and wide for decades, Halsey has always preferred to edit on his own territory. He maintains an editing suite in his home under the Hollywood sign. He has taken a step back from high-stakes Hollywood blockbusters in favor of smaller, independent films. After mentoring the likes of Arthur Schmidt [Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Forrest Gump (1994)] and Glen Farr [The Right Stuff (1983)], who have gone on to become top-notch editors, Halsey is now teaching his daughter Morgan to carry on the family tradition.

With over 70 film and TV credits to his name, Halsey has no intention of slowing down. “My goal is to do 100 pictures!” he exclaims.

CineMontage interviewed Halsey in January.

CineMontage: How did your early experience on the TV show Peyton Place prepare you for a lifetime of cutting features?

Richard Halsey: I learned what I call the basic principles of editing by watching another editor. I was George Nicholson’s assistant. I would do the assistant work very rapidly and then I would sit there and watch.

Peyton Place was shot and structured like a feature film. Fox was very well organized and they had a system: master shot, mini-master, two shots, over the shoulders and close-ups. If you didn’t conform to this pattern, you were gone! It’s great to have those rules, but once you learn them, throw them out the window [laughs]. I think what helped me most was that I was good with people — and I got lucky!

CM: So watching George Nicholson and working at Fox prepared you well.

RH: Yes, Payday [1973], starring Rip Torn, was the second picture I edited. Basically my first cut was almost the final cut. Financially, it was a disaster but it got critical success and made it on to all the Top 10 critics lists in the United States.

We had an opening in the movie where Rip Torn sang the title song “Payday,” and then went into another called “She’s Only a Country Girl.” Both songs were written by Shel Silverstein. Anyway, the producers said Rip Torn can’t sing the opening song and asked me, “Richard, what can we do?”

My big contribution to that film was that I suggested just cutting out the opening song. We hear it in the background as he’s approaching the club, we go into the club and we go right to “Country Girl.” “Brilliant idea! Can you do it? How long will it take?” they asked. I said, “Give me a half hour.” I went to the editing room, cut out the whole opening, and played it in the background of the beginning of the film.

CM: How did Payday (1973) get you hired to edit Harry and Tonto (1974) and lead to a long collaboration with Paul Mazursky?

RH: Paul and I were buddies and we played tennis together at Plummer Park. I showed Payday to him and he hired me to edit Harry and Tonto.

CM: What are your thoughts on your collaboration with Mazursky?

RH: He is my favorite filmmaker, number one. Paul and I had similar visions — we knew when we had it. Whenever I worked with Paul, he and I did everything. There was nobody else involved, just the two of us. We made all the decisions. We picked the music together, or he had a concept of the music. And Paul would keep me on for the duration; I would stay on for the making of a poster, and the marketing of the film.

Most of the time, Paul would leave me to work alone, but sometimes he would come into the editing room. I remember on Down and Out in Beverly Hills [1986], my wife was working with me and Paul would say, “Colleen, can’t you give him something, he’s driving me nuts!” I’m kind of high- energy but Paul was projecting because he was so high-energy! So I’d say to him, “Just go to your office and I’ll call you when it’s ready [laughs].”

CM: Can you talk about how you use music to build emotion?

RH: Music was a big influence on me. One example is at the end of Harry and Tonto. Harry [Art Carney] chases a cat on the beach; he thinks it’s his cat that has died. There’s a little girl on the beach, who is played by Paul’s daughter. The two actually sang a song together, but Paul felt kind of uneasy about the song, so we cut it and just played Bill Conti’s music with the cat and the little girl on the beach.

I don’t know how to explain it other than that the music just created an emotional moment; this guy’s life is over, but it’s not over. That’s editing — sleight of hand, creating magic in the editing room. That’s what it is.

CM: Rocky was a defining moment in your career; what are your thoughts as you look back on its legacy?

RH: I think a major contribution to the film was my selection of Bill Conti to do the music. I had gotten Bill the composing job on Harry and Tonto, and then hired him on Rocky. We actually wrote the song for one of the montages in the editing room. Bill Conti did a brilliant job.

CM: How much do you think the music contributes to the story and the success of Rocky?

RH: It’s legendary. I would say nothing can change the tone of a movie more than the choice of the music.

CM: What is it like editing with your wife, Colleen? How is it working with someone with whom you also live?

CM: What is it like editing with your wife, Colleen? How is it working with someone with whom you also live?

RH: Most of the time, it’s really good. In any relationship, some of the time you’re going to ask, “Who’s the boss?” We’ve been doing it so long now that we’ve got a routine down. It’s definitely a plus. The best picture we did together was Edward Scissorhands.

Nowadays, we edit from home. Basically, Colleen will do a pass and then I do a pass with sound and music, and maybe re-cut some of her stuff. Then we work with the director. We sort of bounce back and forth. We used to do a picture and a half a year; now it’s up to five.

CM: What can you say about working with director Tim Burton?

RH: Tim Burton is a really cool guy and an incredible talent. Edward Scissorhands just cut together. Tim only spent 24 hours in the editing room on that movie. I never worked with him directly, but Colleen did.

On Edward Scissorhands Tim gave me a few notes. He had shot three scenes with Edward’s mentor, Vincent Price. The three scenes were scripted consecutively and, when we saw them in dailies, Tim said, “Richard, the scenes with Vincent Price are too good to put all together.” I totally agreed and told him I’d space them throughout the picture, and I knew exactly where to put them. And that was the end of the discussion. I had to play around a bit with a couple of transitions, but coming from Tim that was a big note!

CM: You’ve edited over 70 films, what are your top three?

RH: Well I think Edward Scissorhands would be one; you could pick any movie with Mazursky, and Rocky.

CM: Why do those stand out to you?

RH: Great music, great emotion, the way they made you feel. I like movies that touch me. My movies go for the heart, maybe a little on the schmaltzy side. I like to make people laugh and cry. I really didn’t want to do Beaches, but my wife, Colleen, said, “What, are you crazy?” It’s a tearjerker, and I think it’s one of Garry Marshall’s best movies. It has a great soundtrack — “Wind Beneath My Wings” — really schmaltzy.

I like the human comedy. Straight-up comedy by itself is not my thing. I like the comedy with the drama, the balance, the yin and the yang.

CM: What guides you when you are editing?

RH: I think it’s just in my DNA. If they buy it, they buy it; if they don’t, they don’t. When something goes wrong, that’s when you learn. There are so many pictures where I didn’t learn anything because everything just went right. You only learn when things go wrong, unfortunately.

You’ve got to be really tough and really strong because the business can be really rough. I was Disney’s No. 1 guy for several years, and I got fired on George of the Jungle — a big Hollywood picture. On Christmas Eve, the director calls me and said, “Richard, I hear Beethoven and you’re playing Mozart.” So I made a decision: I’m not doing any more studio films. I’m trusting my instincts.

CM: Looking over your career, what surprises you the most about it?

RH: That I’m still doing it! I see myself kind of like the blue-collar guy; give me the work and I do the job. Editing has never been like work for me, it’s always been like a hobby. I’m gonna keep on editing until I drop. Editing keeps me going, keeps me alive!