by Peter Tonguette

In 1998, when re-recording mixers Rick Alexander and Richard D. Rogers first met with director John Frankenheimer about working on Ronin, there were many subjects that could have been discussed.

The director might have laid out his vision for the action thriller, which starred Robert De Niro and Jean Reno as mercenaries whose task is to obtain a metal case on behalf of assorted bad guys. Meanwhile, the mixers — both of whom had collaborated previously with Frankenheimer — could have asked about the sound world the director sought to create.

Such conversations would have to wait. Instead, during their first meeting, the trio discussed a subject of common interest, and one especially relevant to Ronin, which boasts some of the fastest and most furious chases in a film not called The French Connection (1971).

“Our initial meeting was not even about the movie; it was all about the car stuff,” Alexander says. “Rich Rogers is a car guy. I’m a car guy. I have hot rods. I got my truck driver’s license in 1976, and I did that for a short while.”

Frankenheimer, too, was a car guy. In addition to such classics as The Manchurian Candidate (1962) and Seconds (1966), among the director’s most memorable projects was Grand Prix (1966), which placed audience members on board Formula One racecars. In this case, art imitated life. A noted enthusiast of all things automotive, Frankenheimer, who died in 2002, may be the only filmmaker to be eulogized not only in Variety but also Car and Driver. Upon his death, the latter magazine noted, “His Beverly Hills garage was packed with such goodies as a fiercely customized Mercedes Benz 600SL roadster that had been originally built for the sultan of Brunei.”

In fact, following their first meeting about Ronin, Frankenheimer offered Alexander and Rogers a spin in that very car. “We were out in the parking lot, and John put Rich and me in this high-performance Mercedes and blasted down Olive Avenue in Burbank,” Alexander remembers. “It scared the bejesus out of me. I said, ‘John, aren’t you afraid you’re going to get a ticket?’ And he whipped out a get-out-of-jail-free card.”

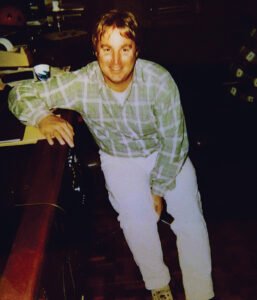

That ride may have been wild, but no less eventful was Alexander’s journey to the mixing stage. The grandson of a special effects camera operator (on his father’s side) and a projectionist at Warner Bros. (on his mother’s), Alexander was born into the business. His father, Richard Alexander, was an accomplished re-recording mixer who began in episodic television before moving onto feature films. His credits include numerous films directed by Clint Eastwood, as well as Taxi Driver and All the President’s Men (both 1976), the last of which garnered him an Academy Award.

Yet, following graduation from North Hollywood High School in 1970, Rick did not immediately follow in his family’s footsteps. Instead, at the height of the Vietnam War, he enlisted in the Air Force. “My draft lottery number was 6, and I was 18 years old when I graduated,” he explains, “so I was getting drafted regardless.”

After leaving the military in 1976, Alexander toiled as a truck driver before finally embarking in a career in post-production. He started at CBS Studio Center as a machine operator before moving onto Glen Glenn Sound, where he became a recordist and then a re-recording mixer. “I’m a techie, mechanical-type person, and you have to have that kind of mind,” he reflects. “I was always trying to push myself to stay in the loop of the new things.”

Television and feature film credits followed, but Alexander received his biggest break when he was asked by supervising sound editors Robert R. Rutledge and Charles L. Campbell to fill in on Robert Zemeckis’ Back to the Future (1985) at Universal Studios as a mixer. Impressed with his talent and hustle, re-recording mixer Bill Varney suggested that Alexander leave Glen Glenn for Universal. “He said, ‘I want you to be a dialogue mixer, and we’ll transition you into taking over the Hitchcock Theatre,’” Alexander recalls.

The following year, he received his biggest feature assignment to date: Frankenheimer’s 52 Pick-Up (1986), an Elmore Leonard adaptation starring Roy Scheider and Ann-Margret. Alexander remembers the project primarily as an example of the challenges of early digital mixing. “Edgy, ugly dialogue tracks” were the norm, he says.

“You would do a boost and then adjust the frequency to find what was causing the edginess, and then either use a filter or equalization to notch it down a bit,” he continues. “You had to be careful with the low frequency because a lot of the room tones, air conditioning and ambient sounds were enhanced by boosting the low frequency.”

As an introduction to Frankenheimer, however, the film proved memorable. “John was a big man — just in his personality alone, he was somewhat overwhelming,” Alexander says. “On the other hand, he was a very nice man. He could be tough and get pushy but, overall, he was very fair and very appreciative of what we did.”

Following 52 Pick-Up, Alexander continued his career with a series of major films for important directors, including Martin Brest’s Midnight Run (1988), Peter Bogdanovich’s Noises Off (1992) and the second and third installments of Back to the Future (1989, 1990). Then, 12 years after first working with Frankenheimer, Alexander was reunited with the director when Rogers invited him to join Ronin.

“I was thrilled to death,” Alexander says. “John was really happy to see me, and I was happy to see him. He had such confidence in Mike Le Mare, the supervising sound editor, and Rich and me.”

Over the course of a five-week mix at 4MC in Burbank, Alexander (who was known for mixing dialogue) and Rogers (who was an expert at mixing effects) evenly divided their responsibilities. “I sat with Rich and helped him with the dialogue pre-dubs,” Alexander recalls. “In turn, when we were doing all the sound effects mixing, Rich helped me. It was a win-win situation. Rich is equally important on the mix of that picture as I am. We both worked very, very hard.”

For the film’s signature chase scenes — in which De Niro, Reno and company pursue (and are pursued) while exceeding the speed limits in Paris and Nice — the mixers turned to material recorded by Le Mare, MPSE, at Willow Springs International Raceway in Southern California.

“Mike had rented a couple of different kinds of cars,” Alexander says. “He went to a shop and had them take the exhausts off the cars and put on different exhausts. And they went out and raced these cars around the racetrack.”

Among the sounds available to Alexander and Rogers were the hums of engines, screeching tires, horns of oncoming cars and the occasional explosion. How to use a particular effect in the mix depended upon the shots selected by picture editor Antony Gibbs, ACE. Throughout the chases, Gibbs alternated between three main groups of shots: angles showing the inside of a car, angles taken from the front hood of a car, and angles surveying the chase from a distance.

“The key thing I tried to do was to make the transitions from inside the car to outside the car not overly jarring, but different,” Alexander recounts. “You want it to be fluid, so that’s what Rich and I tried to do. When someone is jumping on the accelerator, and then it transitions to the outside cut, you want that acceleration sound also on the outside cut.”

Frankenheimer — who would review mixed scenes one reel at a time — deferred to the mixers’ judgment on most matters. “About 60 percent of the time, he left us alone to do our thing,” Alexander says. “He would pick out things that he wanted a certain way, so we would take that in the mix and interpret it the way we felt was correct. He trusted us.”

In mixing one effect, however, the mixers were memorably overruled by Frankenheimer. During a tunnel chase, the hubcap of a police car careens off and rolls toward an inside wall. “We probably worked hours to make the thing sound the way it did,” Alexander says, but when they showed the scene to the director, it did not have the desired impact.

“The hubcap effect came up and he jumped up and threw a tizzy,” Alexander recalls with a laugh. “He said, ‘What the heck is that sound?’ We said, ‘Well, John, don’t you like it? A hubcap comes off and hits the wall.’ He said, ‘Get it out of there! That was a mistake — it wasn’t supposed to happen!’” The mixers acquiesced; the rolling hubcap remains, but it barely makes a peep in the final cut.

Frankenheimer was also adamant about not overusing the score composed by Elia Cmiral, especially during chases. “This is real common in action movies,” Alexander says. “John was such a car guy that he said, ‘We’re not playing any music there.’” On the whole, however, Cmiral’s eerie, evocative score intensifies the film, the title of which refers to a class of Japanese samurai who accept assignments freely — a potent metaphor for the hired hands depicted in the film. “The ronin story is a deep, deep story,” Alexander comments. “Elia did a phenomenal job with the music because it enhanced the feel of the movie. The music was perfect for Ronin.”

The subtleties of the film were also apparent during non-action dialogue scenes, which have a quiet, low-key quality as the mercenaries connive in a cavernous warehouse. “A lot of the dialogue was very low in volume,” Alexander recalls. “To bring it up, the more you pushed the fader, the louder you play it. All the ambient noise comes up around it. We had to do a lot of noise reduction and dip filters to get this low dialogue.”

When Ronin was released in September 1998, the film was a hit with critics and audiences — its director’s first in several years. The chases, in particular, were singled out for praise. “Whether screeching through the narrow, twisting streets of Nice’s picturesque old district or cutting a furious swath through Paris at high speed [and against traffic, even in tunnels], these scenes are nothing short of sensational,” wrote Janet Maslin in The New York Times. “Mr. Frankenheimer directs them in fast, efficient, no-frills fashion because no extra frills are needed.”

Alexander and Rogers mixed such scenes with a similar less-is-more approach. “There are a ton of tracks that you get and you listen to them individually,” Alexander explains. “You put the puzzle together. There are certain things that you want to poke out, to make a statement that you have to work around the dialogue and the music. You want to feel it. You want to hear it. That’s the key.”

For the opportunity it offered to work with a legendary filmmaker — and on a car film, no less — Ronin occupies a special place in the mixer’s filmography. “Because of Frankenheimer,” he reflects, “it meant a lot to me to be able to work on that.”