by Kevin Lewis

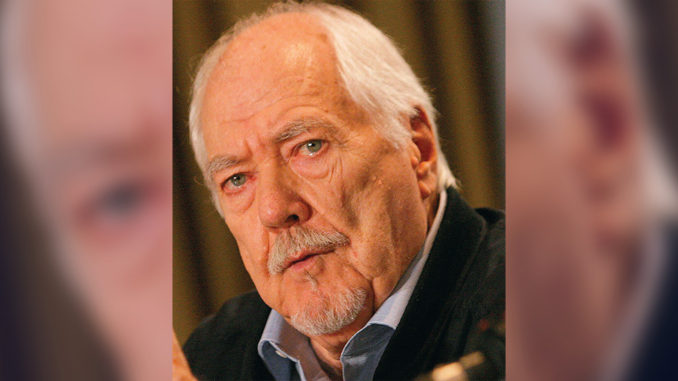

From the beginning of his film career in the early 1950s, filmmaker Robert Altman has utilized sound in unorthodox and spontaneous ways. He has acknowledged being influenced by the films of Howard Hawks, which he would have seen growing up in Kansas City.

Making waves early on as a young director in the 1950s, Altman began overlapping dialogue while directing advertisements and documentaries for the Calvin Company in Kansas City, according to Patrick McGilligan in his book Robert Altman: Jumping Off the Cliff. Altman also reportedly attempted this sound technique on such episodic television series as Combat, Alfred Hitchcock Presents and Bonanza in the 1960s. But it seldom went over well with producers. In fact, “Moving up to his first studio feature, Countdown [1968], Altman was fired for letting his actors overlap their dialogue,” wrote Connie Byrne and William O. Lopez in Film Quarterly in 1975.

David Sterritt, who was the longtime film critic for The Christian Science Monitor and has interviewed the director many times––including for his book Robert Altman: Interviews––claims there is a reason and a rationale why Altman uses overlapping dialogue and sound. “I think his main reason for using dialogue the way he does is very closely related to the way he uses so much camera movement and zoom lensing,” Sterritt says. “A typical Altman film is less a movie to watch than a kind of a place to be in; I think that as a director he likes to be a visitor to the place where his characters are interacting.

“That’s why the camera has this wandering way––its always looking here and there––and why, in at least a handful of his movies, he has attempted to have the camera not looking in the right place,” Sterritt continues. “He did that in Images [1972]. He certainly set out to do that in The Long Goodbye [1973]. Again, in that wandering quality, you are surrounded by a lot of sounds, and it is not all neat and clear or cut and dry.” Sterritt believes that Altman’s rationale for using overlapping dialogue may be that “it makes it harder for producers to interfere.”

Whatever the reasons, Altman’s pioneering use of sound continues to this day, including his latest film, the imminent A Prairie Home Companion. The director has worked with an incredible array of sound editors and re-recording mixers throughout his 50-plus-year career as a filmmaker, never shying away from collaborating with a new crew, which tends to quickly bond with him. CineMontage interviewed several sound people about their working relationship with Altman and how he has enriched and transformed their lives.

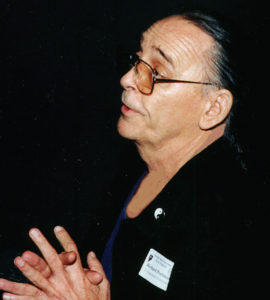

Richard Portman

Richard Portman, CAS, who is now teaching sound as the Gordon Sawyer Professor of the Recording Arts at Florida State University, worked as a mixer for Altman from California Split in 1974 through Health in 1980. Impressed with Portman’s previous work, the now late sound editor for California Split, Kay Rose, asked him to mix the film in a then novel multi-track mix.

“Kay Rose was the finest dialogue editor in the business and she was unmatchable in cutting this innovative dialogue editing,” Portman recalls. “She would cut it into three parts: the main dialogue, the background dialogue and the atmosphere. I kept the same separation in my dialogue pre-dub, assigning them to channels one, two and three. It was slow, time-consuming work and I would be lucky if I averaged one reel a day.”

Dialogue clarity was achieved, he explains, by substituting a line or two from an outtake that was not the director’s choice. But Altman didn’t even comment on the substitution, according to Portman, who adds, “There was never any replaced dialogue on his films. Everything was production sound. We’d steal lines from other takes, but that was difficult too.” If the mixer discovered that one track of dialogue had conflicting noise but another track didn’t, the better recording would be used instead. “All I had to do was cross from the A track to the B track and then back again––so the job became looking for the best track at any given moment and making good crosses,” Portman explains. “That hasn’t changed; most of the production recordings are now done on multitrack recorders.”

Portman credits fellow mixer James Webb, now retired, for the sterling coordination of sound on location, especially among the large speaking cast of Altman’s Nashville (1975). Four-track stereo sound was used in Nashville––for the public address announcer in the film and for sound effects––to accommodate the theatres that were equipped with stereo sound, according to Portman. Although it received no nominations for sound editing or mixing in this country, Nashville was honored by the British Academy of Film and Television Arts with its BAFTA Award for Sound.

“During production, I would ask Altman, ‘What do you want to hear in this scene?’” recalls Webb. “And he knew immediately what he wanted, so he would give me a list of actors’ names that he wanted to hear, and that meant that they would all get radio mics. Of course, when everyone is saying something different, and I’m trying to listen over a pair of headphones, it becomes a Tower of Babel.” Webb also explained that Altman accepted the unavoidable extraneous sounds that the body mics picked up. He recalls in particular the noises created when Elliott Gould and George Segal embraced in California Split and when Michael Murphy moved in his drip-dry suit in Nashville. They could not be fixed in post-production, he said.

Altman was not a micro-manager, according to Portman, and never objected or interfered with the mixing: “He never came to the stage; he knew that we would do the best job we possibly could.” Instead, the mixers would preview the material for Altman at a rented theatre. “We would play back reels for him,” he says. “I asked him once why he didn’t come to the stage, and he said that he just wanted to hear what we had done.”

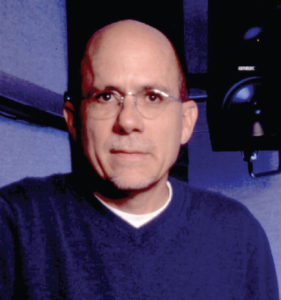

Richard King

Portman’s friend and colleague Richard King, who is a sound editor and designer, enjoyed his two-film association with Altman as a supervising sound editor on Kansas City (1996) and The Gingerbread Man (1998)––the latter with Randy Akerson as co-supervisor. Both films were sound edited using ProTools. Altman has a “great way of getting you on his wavelength and doesn’t have any interest in telling you exactly what to do,” says King. “Somehow, he makes you understand what it is he is going for, but quite frankly, he often doesn’t know himself. It’s all an exploration for him. The outcome is not a fixed goal. He’s looking for input from other people.”

Kansas City was a straight forward period piece with jazz as a thread, according to King. “The body of the film we tried to make as detailed and accurate as possible,” says King, “While the other film, Gingerbread Man, was a straight-ahead thriller.”

Altman, however, wanted the unexpected on the latter project. “The first thing he told me was, ‘I don’t want any music in this movie––I don’t want any score, I don’t want any source music; I want to create the music from the environment,’” King reveals. Because it was about a hurricane moving toward Savannah, he wanted King to design sound around the wind and the objects displaced by the wind.

“He wanted all natural sounds, and to create a score from that,” explains King. We did a temp dub with that in mind. The opening of the film is a tracking shot of Savannah and its environment from a helicopter, so you are hearing radio static of various kinds and voices filtering in and out. Occasionally, I’d put in a little bit of music that would beep on the radio, and he didn’t want that. I had a guy whistling a tune in an alley, and he didn’t want that. He set that as his challenge that he would do a movie without music.”

In the end, the producers wanted music. And they convinced the director to go with a score––by Mark Isham. “But, even with the score, many of Altman’s original sound ideas were retained,” acknowledges King.

Matthew Iadarola

Re-recording mixer and recordist Matthew Iadarola worked with King on both Kansas City and The Gingerbread Man, as well as on an earlier Altman film, The Player (1992). Describing his role in the post-production process, he says, “I was the re-recording mixer for music and dialogue, the guy at the end of the process. On all three Altman films, I worked closely with the late Geraldine Peroni, the picture editor [and a longtime colleague of Altman’s]. We would put things together, and she knew Altman well enough that she would guide me.”

On The Player, Iadarola knew right away that Altman was not obsessive about having things done his way in the mixing process. “He gave me one note,” the mixer recalls. “We would get notes, but they were more about keeping things natural. I remember in Kansas City there was actually some ADR. Even though we looped it, it was not so much for clarity, as it was for feel.”

The Player astonished critics and audiences at the time because of its sweeping, nearly eight-minute-long tracking shot across a studio lot that included a large cast of actors and extras. Many of the characters had body mics, so that casual but crucial dialogue could be picked up by the recording equipment when the camera swept by. “On The Player, there was only one looped line in the whole movie––and that’s because a radio mic on one of the actors went out during that opening tracking shot,” Iadarola reveals.

The Player recorded sound on three band 35mm magnetic tape. “At that time, everything was single-stripe mag, and you could not have three mics that were recorded at the same time on three separate machines because they would phase and cancel each other,” Iadarola explains. “So they were transferred together to the three bands of full-coat magnetic tape––and that way, they were locked into registration and the sound didn’t phase. But because it was three bands, you could get in there and do the fades and the adjustments by manually editing the soundtrack––things we are now able to do with ProTools. I enjoyed those days, but I don’t miss them.”

Robert Altman has worked with an incredible array of sound editors and re-recording mixers throughout his 50-plus-year career as a filmmaker, never shying away from collaborating with a new crew.

The production dialogue for Kansas City was recorded on a Tascam DA-88, a digital eight-track audio recorder. “This means that up to eight microphones were used for each take on location,” says Iadarola. “Boom and radio mics were hidden in plants and other places.” The film used only a few ADR lines. “For the first time, we used some looped group lines,” he continues. “It’s not that Bob would not use ADR as a rule, it’s just that the need for it was greatly reduced by the amount of microphones that were used for each take on location.”

Iadarola learned many valuable life lessons from Altman, but one particularly stands out for him. “He told me not to be afraid to be on the nose––when I was overly concerned about being too obvious,” the mixer admits. “Coming from him, who is certainly not a director who specializes in clichés, it was ironic because of his subtlety and nuance. It’s a great concept that sometimes it is necessary in storytelling to underline things.”

Iadarola finds authenticity in Altman’s decision to replicate the natural rhythms of everyday life through overlapping dialogue and music. “Working with him changed my whole career because I specialize in dialogue and music––and he is a master storyteller with both of these,” he confesses.

Eliza Paley

Eliza Paley, who has been a supervising sound editor for Altman for over a decade, also agrees with and appreciates the filmmaker’s quest for authenticity in sound.

She began her association with him on the masterwork Short Cuts (1993) and has worked on every Altman film that has posted in New York since then, including A Prairie Home Companion. “I feel very privileged because, not only do I love his work, but Altman is a director who thoroughly appreciates sound and uses it to its fullest for overlapping dialogue and interesting transitional moments.” She characterizes the final mix sessions on his films as “very relaxing, collaborative and creative” and is quick to add, “He understands the process and respects the fact that it takes time to weave all the elements together––especially since he records so many tracks in production.”

Short Cuts contained some scenes where there were a great deal of overlapping conversations going on at once, Paley recalls, but Pret a Porter (1994), on which she was the dialogue editor, proved to be an extreme case, with “groups of four or five people overlapping with other groups of three to five people.” The scenes in public spaces, such as an auditorium or the lobby of a hotel, which involved up to 17 people, were especially challenging for Paley as dialogue editor.

The film’s supervising sound editor Skip Lievsay, she recalls, mixed down 16 tracks to six or eight tracks for one group, and four or five for another. “Then we dialogue editors would piece them together according to location and characters in such a way that the mixer, Lee Dichter, could make sense of it,” she says. “It was more like putting together a puzzle than traditional dialogue editing; it was challenging in a completely new way and lots of fun.” Paley used a similar approach on subsequent Altman films on which she was supervising sound editor.

For Altman’s penultimate feature, The Company (2003), the director was very concerned about recreating the sound of the dancers’ feet on the dance floor. “This was something they could not record well during filming, with multiple cameras and audiences present,” Paley explains. An inaccurate sound would break the organic quality of dance. “Altman said, ‘This is a very specific sound. We have to have that sound,’” she recalls. “The only way to achieve that was to record the Foley on location––that is, on a real dance floor with the actual dancers who had performed during filming. I was thrilled with the outcome.

“The Foley just blended right into the production track,” Paley continues. “You can’t have one Foley artist do that the same way the actual dancers do it. They don’t have to be taught the dance because they know it, and it is in sync to the music. So once they hit it in the beginning––once you get the first one in––everything else falls in. The quality of the dance is so unique that it would be really hard to recreate it in any other way.”

“[Robert Altman has] a great way of getting you on his wavelength and doesn’t have any interest in telling you exactly what to do,” – Richard King

Eric McAllister

Eric McAllister, who served as supervising assistant sound editor on A Prairie Home Companion, also applauds the search for genuine sound by Altman. He first worked with the director on The Company, on which he was supervising sound assistant, and then on the miniseries Tanner on Tanner (2004), where he was sound effects editor.

Praire has overlapping dialogue backstage mixed in with a performance onstage. The stage performances at the Fitzgerald Theatre in St. Paul, Minnesota were recorded using a 32-track machine. Sixteen tracks were used for the mics on the stage because of the stage band. When the performers walked onto the stage, they would be wearing lavalier microphones, representing the other 16 tracks. On all of the Altman films on which he worked, McAllister says that the performers would be fitted with lavalier mics.

“When the Prairie dailies came in, assistant editor Jane Rizzo had to go through and name every track with the person’s mic and character name on it,” before it was handed to the mixers and sound editors, according to McAllister. The mix on Prairie took five weeks.

McAllister, who prepared the sessions for the dialogue editor and mixer, is impressed that Altman resisted the urge to use ADR on the vocals because he wanted to preserve their fresh, naturalistic stylizations. “Altman doesn’t want a lot of sound manipulation,” McAllister says. Then, after a pause, he adds, “He doesn’t really want any.” In fact, the charm of the movie, which is based on the long-running radio show conceived and hosted by Garrison Keillor, is that we believe the actors are the vocalists on the radio.

“Altman is very singular in his style,” McAllister offers. “He lets his movies just kind of happen, which is great. The rarest thing is someone who just makes his movie by letting it come together like an organic process.” At one point during the mixing of Tanner, McAllister queried Altman on the motivation behind overlapping sound, music and dialogue. “He told me that he doesn’t mind making the audience work––just like in the real world,” he says.