By Jennifer Walden

AI-generated voices and voice cloning technology have caused quite a commotion recently.

Last year, an unconventional short film titled “In Event of Moon Disaster” won the News & Documentary Emmy Award for Interactive Media: Documentary. “Documentary” summons up other words such as “factual,” “real,” “non-fiction,” and “truth.” Interestingly, this film asks the question, “Can you spot a deepfake?”

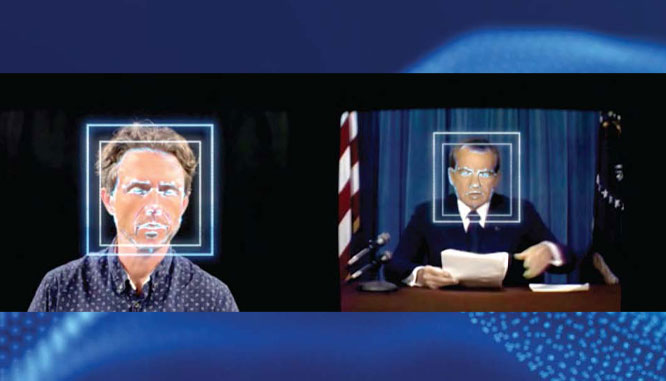

“In Event of Moon Disaster” (produced by MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality and directed by Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund) utilized machine learning technologies from Canny AI and Respeecher to manipulate both the picture and sound of a broadcast from 1969 in which President Nixon delivers a speech about the Apollo 11 mission. He’s reading a contingency speech that was actually written in 1969, just in case the Apollo 11 mission ended in disaster. Nixon never read it aloud on camera. He didn’t need to. So his voice for “In Event of Moon Disaster” was AI-generated – i.e., fake.

Another documentary film released in 2021, “Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain,” also used an AI-generated voice – in this case to read a few lines that Bourdain wrote but never recorded. This film sparked a huge conversation in the film industry about the use of AI voice cloning. MPSE award-winning supervising sound editor Al Nelson — who supervised the film’s sound but wasn’t directly involved in the voice cloning process — explained that dialogue editing (from feature films to news clips) sometimes involves cutting together pieces of lines in order to create a more concise, clear sentence that is grammatically correct. These edited dialogue chunks are widely known in the reality TV world as “Frankenbites.”

(This practice isn’t unheard of in journalism, too. In fact, I’ve tightened up some quotes in this story for readability and clarity, but they all retain the essence of what the source said.)

Nelson said, “It’s not done to twist or manipulate the context, at least in my experience. It’s done to make a more concise statement. And that’s what happened with this film. The dialogue was based on something that Anthony had written, and rather than have an actor read it or have it subtitled, director Morgan Neville wanted it to be read because it was important to the opening. We had gotten a few words that were AI-reproduced and we plugged them in to our edit. It was about trying to make it a little bit more believable, to engage the viewer and not have it feel disjunct. Morgan’s intention was to immerse the audience, not to mislead them. This can be a useful tool when it’s not used in an oppositional way. And in this case, it was useful.”

As author J.K. Rowling via Albus Dumbledore has said, “Understanding is the first step to acceptance.” So let’s dive into two leading AI voice generators being used in post-production — Respeecher and Sonantic — to understand how they work, how they’re being used, and how they might play a role in the future.

Respeecher

In addition to “In Event of Moon Disaster,” Respeecher was used to create the voice of Young Luke Skywalker for the Disney+ series “The Mandalorian,” and for the voice of Vince Lombardi in last year’s pre-Super Bowl commercial “As One.” It was most recently used to clone the voice of famous Puerto Rican sportscaster Manuel Rivera Morales for a Medalla commercial. Respeecher’s API is used as part of Ver-tone’s MARVEL.ai platform. And their project list keeps growing.

Respeecher’s main approach to AI-voice generation is through speech-to-speech. This means a line of dialogue is recorded in one voice and then converted to a target voice. The benefit of speech-to-speech is that emotional nuance, inflection, pacing, and projection level (whisper to shout) are directly imparted to the target voice.

Alex Serdiuk, Respeecher CEO, explained that their deep learning models were built to understand the differences between voices in the acoustic domain. Their models compare timbres between two voices, so that one voice is literally driving another. “Respeecher is not tied to any specific vocabulary. That’s why our models are emotional to the extent that humans are emotional. Your performance isn’t being touched or changed during the conversion. Only the vocal timbre is being changed. So you can perform the emotion you need but your voice will sound very different, like you’re using different vocal chords,” he said.

To create a voice clone, Respeecher needs roughly 40 minutes of dialogue from the target voice. The emotional range in that dataset should be similar to the emotional range needed for the conversion. “For most of our projects, we’ve had to deal with existing data because we’ve done quite a bit of voice de-aging and voice resurrection. So we were limited to what data has already been recorded,” said Serdiuk.

When creating a voice clone from archival material, Respeecher prefers to handle the cleaning and de-noising, “because we know how our models react to this type of processing,” Serdiuk explained. They use a variety of audio restoration tools, from third-party noise reduction solutions like iZotope RX to proprietary tools for dialogue enhancement. It’s a process that’s continuously improving. “Many of the projects we worked on in 2020 had a very slight tape hiss on the output, but on a project we delivered this December, we were able to remove it all. The target material sounded like it was recorded yesterday and not 40 years ago.”

For a simpler use of Respeecher (for those not looking to clone a voice), they offer a Voice Marketplace and web browser application called TakeBaker that can be licensed for a reasonable monthly (or yearly) fee. The Marketplace offers over 40 target voice options across a range of ages, different genders, with even non-human options such as dogs.

Since TakeBaker is a web browser application, you’ll need to connect a microphone to your computer and perform the line(s) yourself, or upload short dialogue clips (as .ogg, .wav, .flac, or .mp3) that you want to convert. Again, performance is key. There are currently no editing options in TakeBaker, so if you don’t perform the line perfectly, then you’ll have to re-record it.

Audio quality is important, too. A good-sounding mic, proper input levels, and a quiet recording environment will result in a more accurate conversion.

Pitch adjustments can be made to the target voices. For instance, if a deep male voice option needs to be a bit deeper, that can be adjusted prior to the conversion.

The conversion takes a few minutes as the model analyzes the input voice and the target voice, and then renders the output. The take(s) can then be downloaded as 48k/16-bit .wav files.

For supervising sound editor/sound designer/actor Abigail Savage at Red Hook Post in Brooklyn, NY, Respeecher’s Voice Marketplace and TakeBaker tool have been helpful for creating background vocal textures for film projects. For instance, if a scene has a group of people chatting together in the background, Savage would typically record a loop group, or record a few people from around the studio, depending on time and budget. In the latter case, though, she’s limited to the range of voices available in the studio at that time.

“Instead, I’ve been using Respeecher to perform the lines. I can record both sides of any conversation and then go through their AI voices to find ones that fit. I’m creating my own loop group that way. It’s incredibly fun,” said Savage. “You’re completely controlling the performance, too. You’re not trying to tease a performance out of somebody when you know exactly what you want. You can just record yourself saying it and then transpose that onto a different voice.”

Savage noted that while the technology has improved since she started working with Respeecher, it’s still not perfect. “Initially, there was a performative flatness. The target voice I was leaning towards wouldn’t necessarily sync with the performance I was giving it. There is still a disconnect there, but it’s something that’s already gotten better with updates,” said Savage. “Another issue is the amount of time it takes for the conversion — how long it takes to generate a voice. Making that workflow faster is something that’s constantly improving, too.”

According to Serdiuk, Respeecher is currently working on a possible standalone app, or plugin for Pro Tools or Audacity. For Savage, having a Respeecher plugin that could be inserted on a track, with real-time voice transformation, would be ideal. “The next best thing would be a solution similar to iZotope’s RX Connect, which allows you to send clips from Pro Tools to the standalone application for processing,” noted Savage.

Respeecher does offer a text-to-speech option — available in TakeBaker — but unlike speech-to-speech, it doesn’t have an emotional range. Another issue with text-to-speech is that it’s limited to language models and vocabulary. For text-to-speech options, Respeecher offers four accents: US English, GB English, CA French, and FR French.

Sonantic

Sonantic’s main approach to AI voice generation is through text-to-speech. If you’re imagining a robotic readout, then you’re miles off the mark. Sonantic offers “fully expressive voice models,” meaning you can choose from a range of voices and then change the emotion of the read — like “happy,” “sad,” “fear,” “shouting,” and “anger” — and alter the emotional intensity of the read — low, medium, and high.

There are two options for using Sonantic. The most basic option is to license the software and use Sonantic’s desktop application to choose from a variety of pre-made voice models on the platform. Option two is to work with the Sonantic team to create a custom voice model. According to John Flynn, Co-Founder and CTO of Sonantic, “We’re actually in the process of building out plug-ins for various audio softwares and game engines and look forward to sharing these with our customers.”

Inside the application, text is converted into AI-generated voice files that appear on a timeline. In the upper area of the application window, you can choose a voice model, type what you want it to say, choose the emotion and intensity of the read, and also adjust the pace of the read to control timing, rhythm, and emphasis of particular words or phrases.

The audio editing area in the lower portion of the window looks like a traditional Digital Audio Workstation (DAW). You have the ability to zoom, trim, and ripple edit the AI-generated voices as sound files.

Sound files can be exported as .wav files in 44.1k/16-bit or 48k/24-bit, with higher sample-rate options coming later this year.

Flynn said: “Text-to-speech is great for two things: speed and experimentation. Sonantic can batch-generate thousands of lines of dialogue and export them into different file names and folder structures very quickly. Text-to-speech also allows our customers to trial different voice models to see which fits a character best.” It’s an approach that works well for game developers and animation studios during story development.

Sonantic will soon offer speech-to-speech capabilities for AI voice generation, according to Flynn. “This hybrid approach is the best of both worlds,” he said.

Flynn sees speech-to-speech as a way for Sonantic users to finesse performances of specific lines, as opposed to being a main approach to how their software is used. He said, “I would guess that approximately 5% of a script would be edited using speech-to-speech. A lot of our customers will do batch generation in the early stages of a production, and when moving towards a final cut, they will spend time finessing a small portion of the lines to get the performance they need. There may be one line that just isn’t quite right, and it’s easier to verbally direct how you want it to sound. The software will mimic the exact intonation it is given.”

For more complex projects, Sonantic can work with clients to create custom voice clones, as they did with actor Val Kilmer to recreate his voice after the damaging effects of throat cancer. For this, they need roughly three hours of clean material with the right range of coverage, from phonetics to emotional styles.

But in the case of Kilmer, they could only use historical recordings. “We had to strip away the background noise while keeping the quality of his voice intact. After cleaning the audio samples, Sonantic was left with ten-times less data than typically needed. This led to the creation of new algorithms, techniques, and models that have since been incorporated back into the Voice Engine, strengthening its ability to handle difficult voice content in the future. Overall, we created 40 different options before finalizing Val’s prototype,” said Flynn.

Creating a custom voice clone can take anywhere from six to twelve weeks. But once it’s done, the voice model will appear in the user’s Sonantic platform alongside the other voice models.

Speaking of the Future

Supervising sound editor Mark A. Lanza, MPSE, President of Motion Picture Sound Editors, sees the potential of this technology for use in legacy projects, “where it’s the seventh, eighth, twelfth iteration of a movie, and they want to bring back an actor who had done one a decade ago and has since passed. With the leaps they’re making in visual mediums — being able to visually recreate an actor — they can now sonically recreate the actor as well. The implications are amazing. You can have any actor who’s ever lived be in your movie. You can’t tell the difference visually more and more, and you’re not going to be able to tell the difference sonically,” he said.

As a sound designer, Nelson is excited to use AI-voice technology as a way to create new languages for films, or create new alien-sounding voices. “This creates a whole new realm where you can take this library of particular performances, load it into this program, and use parameters to manipulate the sound to make a whole different language that doesn’t exist. You could swap out all the consonants for different consonants. This might be the next level, but I hope that we’re still keeping that performance — that serendipity — that exists when you have actual humans involved in the process,” said Nelson.

Serdiuk sees AI voice generation not as a competition for actors but as a way for them to expand their range. “Our tech is heavily reliant on voice actors because they need to perform the part. Having our technology as part of their business, they can get more jobs because they’re not tied to the voice they are born with. They can perform in a different gender or different age just by picking a different voice from the library,” he said.

As speech synthesis develops and improves, it helps establish clearly defined legal and ethical policies that can help deter the deceptive use of this technology. Respeecher is also exploring ways to watermark content generated by their software. For documentaries, being forthcoming about using voice clones or AI-generated voices could make it more acceptable for audiences. Maybe that’s done by having a title card up front saying an actor’s replicated voice was used in a project — as was the case with Savage’s latest project.

“In my opinion, bringing awareness about the tools is one of the best measures that we can take in order to defend ourselves against the tools being used nefariously,” concluded Serdiuk.

Jennifer Walden is a frequent CineMontage contributor who specializes in post-production technology.