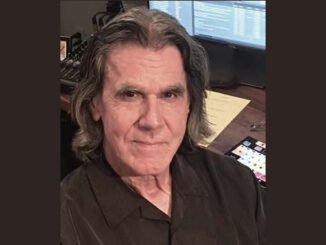

by Peter Tonguette

To hear Robert “Bubba” Nichols describe it, working as a recordist sounds a little like serving as a fighter pilot.

Okay, okay — pilots operate under life-and-death pressures in the air, while recordists toil under far less challenging conditions on a re-recording stage. Even so, both professions demand precision and punctuality. When assigned to a film or television show, Nichols must adhere to a tight schedule as he works to assure that the sound elements for which he is responsible have been delivered properly. After determining that they are ready for the ears of the re-recording mixer, Nichols transfers the material to the mixing board, and the soundscape of a project starts to solidify.

Photo by Martin Cohen

“My job is to listen and make sure that the music is being laid down properly and we don’t have any hiccups,” Nichols says. “You don’t want any sound effects or any kind of dropouts in the music, obviously, and if you hear something, you flag it right away. Downtime is a thousand dollars a minute. When reels are rolling, you keep rolling. There is no time for errors.”

The fast pace and high stakes might be familiar to the characters who headline one of Nichols’ favorite projects, the military action film Top Gun, which racked up close to $180 million at the box office when released in May 1986. Featuring a group of bold, brazen naval aviators whose derring-do has led to their admission to a flying school, the Paramount Pictures release was directed by Tony Scott and stars Tom Cruise (Lt. Pete “Maverick” Mitchell), Val Kilmer (Lt. Tom “Iceman” Kazanski), Anthony Edwards (Lt. Nick “Goose” Bradshaw) and Kelly McGillis (Charlotte “Charlie” Blackwood, an instructor and romantic interest).

“To this day, if I was on a desert island, Top Gun would be one of the five movies I would want,” comments Nichols, who represents the recordists classification on the Guild’s Board of Directors. “It’s as simple as that.”

Nichols, however, did not have to attend the equivalent of a flying school to learn his trade. As the son of longtime MGM sound department employee Bob Nichols, the youngster grew up in the shadow of the industry, spending summers on the lot. “People would go to summer camp, but I would go to my dad’s work,” Nichols recalls. “I was pushed onto different soundstages — The Courtship of Eddie’s Father,Medical Center — almost like babysitting. He would say, ‘Stand behind the mixer’ or ‘Stand behind the boom man,’ and then would drop me off there for two hours.”

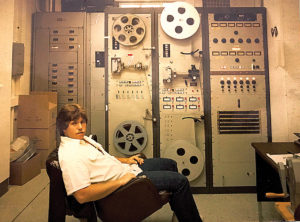

Sound was an early enthusiasm for Nichols, who was given a reel-to-reel tape recorder as a child. “I’d record radio stations and make my own mix tapes with a microphone,” he recalls. Nichols ultimately entered the business after his father arranged a “one-day job” for him at Samuel Goldwyn Studio in the late 1970s. “My dad said, ‘What did you think?’” he reveals. “I said, ‘Dad, I can’t do this job. It’s a boring job, and I don’t know how you’ve done it for this many years.’ Next Thursday, I got paid and I said, ‘Dad, I can do this job, I can do this job!’”

Sound was an early enthusiasm for Nichols, who was given a reel-to-reel tape recorder as a child. “I’d record radio stations and make my own mix tapes with a microphone,” he recalls.

In the end, Nichols found a home at Samuel Goldwyn Studio, which by 1980 was known as Warner Hollywood Studios. He first found work in the studio’s film vaults — “I was taking the splicing tape off the tapes and was degaussing hundreds of thousands of feet of mag film so they could reuse them” — before finding his calling as a recordist. His first feature film was The Final Countdown (1980) starring Kirk Douglas.

“As a recordist, you work on a stage and prepare all the playback machines,” Nichols explains. “You get the technical specifications from the sound supervisor, music supervisor and picture editors, knowing what sample rate you’re running at and what film rate you’re running at, so it all can be in sync. We patch all of that information to the mixers on their mixing boards. At the time, we were using Quad-Eight boards.”

By the time he got the call to work on Top Gun, the recordist had honed his craft on several high-profile features, including Frances (1982), Rocky III (1982) and Moscow on the Hudson (1984), and had been mentored by recordist Walter A. Gest. On the film, re-recording mixers Rick Kline, Donald O. Mitchell and Kevin O’Connell, CAS, led a team of three recordists, James Cavarretta, Mike Haney and Nichols — a rarity, according to Nichols. “This was a first for a lot of things,” he comments. “Most of the time, you have just one or two recordists to oversee dialogue, music and effects, but this movie was going to be something big and they wanted three. They pulled us all together.”

Nichols was tasked with overseeing the music track, which was stocked with songs that became synonymous with the movie, including “Mighty Wings” performed by Cheap Trick, “Hot Summer Nights” performed by the Miami Sound Machine, “Playing with the Boys” performed by Kenny Loggins and, most famously of all, “Take My Breath Away” performed by Berlin. “This was one of the better soundtracks that ever was,” the recordist observes. “It opened up a can of worms because other bands and musicians said, ‘Well, wecan make a soundtrack.’ There were soundtracks prior to it, but not like this.”

Nichols continues: “To set up a stage for Top Gun in the morning, it would take almost two hours just as far as patching goes. Then you got the recorders together and the picture together. You tried to run a little bit of a test five minutes before, because as soon as the mixers walk in, they want to press that button — ‘Let’s go and start mixing.’ You don’t want to have any issues.”

With his headphones — or, as he calls them, “cans” — in place, Nichols plowed through one scene at a time. “You start with Reel 1, Scene 1,” he says. “You just stay with one particular thing — music — and you stay with it until you’re blue in the face.” Because multiple tracks were used, there were often as many as 50 pre-dubs per reel. “You would have the gunshots and the flybys and the F-16 flybys,” Nichols explains. The music was also split into multiple tracks, too; vocals might be on one and strings on another. “My responsibility is not mixing them but listening to them,” he adds.

During the process, Nichols listened to the music alone; without the benefit of hearing dialogue or effects, the dips or fades in a passage of music occurred out of context. “Eventually, we took that reel and put in another reel and another reel, and mixed those all down to what you hear on the screen,” he reflects. “Sometimes we went down and watched the playback, and I said, ‘Wow! Okay, now I get it.’ Before that, I was listening to it as music, and it kind of dipped or went high, and you don’t understand why. Well, because the dialogue is coming in.”

Although Nichols had to keep his mind, and ears, on the music of Top Gun, he is equally effusive in praising the work of supervising sound editors Cecelia Hall, MPSE, and George Watters II. “They were on point as far as having the right sound effects,” Nichols observes. “If there was a Kawasaki motorcycle that Tom drove, it had to be that same bike for the sound effect. At that time, nobody did anything like that — you know, ‘a train was a train, and a car was a car.’ It really made a difference.”

“As a recordist, you work on a stage and prepare all the playback machines,” Nichols explains. “You get the technical specifications from the sound supervisor, music supervisor and picture editors.

Nichols also commends director Scott, who went on to make such accomplished films as Days of Thunder (1990), True Romance (1993) and Crimson Tide (2005) before his death in 2012. “Tony was always very cool,” Nichols says. “We had a cigar together a couple of times — what a treat. A little bit loud. A little cranky after 13 or 14 hours, but who isn’t?”

The two-month-plus mix kept Nichols away from his wife and children at home in Manhattan Beach. “It got to the point where I just got a room at a Holiday Inn,” he says. “It was just easier for me to stay there than come back, because I would get off at about 12:30 a.m. and have to be back at 6:00 a.m. It was probably one of the longest movies I’ve ever worked on, but also one of the most rewarding movies I’ve ever worked on.”

Audiences were no less effusive. Prior to the release of Top Gun, many military movies had taken as their subject the trials and tribulations of the Vietnam War;Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978), Karel Reisz’s Who’ll Stop the Rain (1978) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) considered the tragic costs of the conflict. Taking a different tack, Top Gun celebrated the men and women who served in uniform in an entertaining, unapologetic fashion.

Miramax/Photofest

“The timing was amazing,” Nichols reflects. “America needed this. It boosted up the military morale. They all wanted to be Maverick. There are quotes that are still being used today: ‘Need for speed,’ or ‘You can be my wingman anytime.’”

The film was honored at the Academy Awards, receiving nominations in all three post-production categories: Kline, Mitchell, O’Connell and production mixer William B. Kaplan, CAS, for Best Sound; Billy Weber, ACE, and Chris Lebenzon, ACE, for Best Film Editing; and Hall and Watters II for Best Sound Effects Editing. The prize for Best Original Song was awarded to the creators of “Take My Breath Away,” composer Giorgio Moroder and lyricist Tom Whitlock.

Nichols attended the ceremony to root on his colleagues, but perhaps even more thrilling for the recordist was the premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, when he knew his hard work had paid off.

“I’ll tell you, I got goosebumps,” he reflects. “Coming out of the theatre, my shoulders were high and my chest pumped out. I thought, ‘Wow! I had a piece of that.’ It was just like being a proud papa.”