By Rob Callahan

If you’re going to fight for what is right, it’s important to be strong. But it’s perhaps even more important to be tough. Our union is both.

Since I last penned this column, IATSE has won two high-profile organizing campaigns led by post-production employees. Together, the Survivor and Shahs of Sunset victories present a study in contrast: One was a near instantaneous win against a hugely successful broadcast television institution, the other a protracted and hard-won bout against a lesser-known basic cable series.

In conjunction, these two wins reveal our organization as a well-rounded fighter. We are a power-puncher capable of landing knockout blows early in a fight, and we also have the stamina to take hits and keep swinging into the late rounds.

The Survivor campaign offered up relatively little news to report; the crew secured its contract too swiftly and decisively to leave much to say about the contest. Over the course of many quiet conversations, the post crew of Mark Burnett Productions’ long-running series overwhelmingly decided that they wanted union representation. Survivor was no sweatshop; the show’s employees had good jobs. They enjoyed working on a wildly successful show that has, over the span of its 14-year run to date, done perhaps more than any other to define the genre of reality television.

But these employees, while happy in their gigs on Survivor, were also keenly aware of the larger trends in the industry. They had seen colleagues on other successful unscripted shows earning health and retirement benefits with increasing regularity. Together, the employees of the show’s post crew decided it was time Survivor came under an IA agreement.

Photo by Preston Johnson

It took many years for the Survivor post crew to reach the conclusion that it should be a union show but, once the decision was made, change came quickly. The IATSE sent a letter to the crew’s employer, demanding an immediate start to contract talks. When the company failed to respond right away, the post crew walked off the job on August 13, calling into question the scheduled premiere of the show’s 29th season. Our picketers barely had time to apply sunscreen before the strike was over. Within hours, management agreed to recognize the union in order to bring the crew back to work. A few days later, we had a union contract, winning retroactive benefits and eight-hour workdays.

The fight for a contract at Shahs of Sunset began similarly. The show’s post crew members had no unusual complaints about their jobs, but they had been following our recent momentum in organizing unscripted television; they shared the general enthusiasm for a future in which folks working in reality TV could come to expect the same benefits and safeguards long taken for granted by those crafting scripted fare. As a group, they overwhelmingly decided to take action to make Shahs — a fourth-season docu-soap produced by Ryan Seacrest Productions for Bravo — a union show.

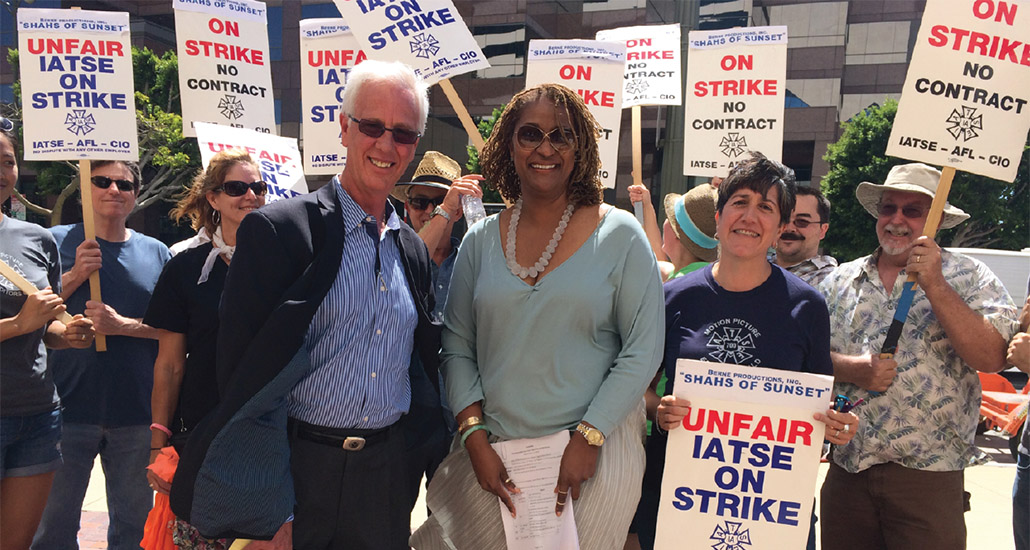

On September 10, after Ryan Seacrest Productions failed to respond promptly to a letter requesting contract negotiations, the post crew members halted their work on the show. They were joined later that day by members of the show’s production crew. With post and production both shut down and much work remaining to be done on the show before its scheduled premiere October 13, the crew appeared to be in a strong position to attain a timely deal.

At first, weather seemed to present the only unusually difficult factor in the Shahs strike. A mid-September heat wave drove up temperatures for our picketers outside of Ryan Seacrest Productions’ offices on LA’s Wilshire Boulevard. Folks were scorched and sweaty as they walked the picket line, but spirits remained high. The executives may have been indoors enjoying air conditioning, but they had no show without the crew. The sun’s glare notwithstanding, we were the ones turning up the heat.

As the strike neared the end of its second day, Bravo made a move signaling that this would prove an unusual ordeal. The network announced it would indefinitely postpone the season premiere — a declaration that revealed its willingness to incur significant losses in advertising sales in order to remove the pressure of a looming airdate.

Viewed in the limited context of just a single show, Bravo’s move made little sense. The cost of returning the crew to work under a union contract with health and retirement benefits was relatively trivial, while the cost of scuttling a scheduled premiere date was considerable. But just as the striking crew was motivated by big-picture considerations, so too were Bravo and its corporate parents taking into account larger trends within the industry. This particular domino mattered less to the companies than all those that might fall after it.

So began a difficult struggle that would stretch on for an entire month. Though our union remained confident that our resolve would ultimately prove greater than the employer’s recalcitrance, the outcome of the fight was never certain. We braved many dark days under the brazen LA sun. Local 700 offers modest strike relief benefits for folks who miss multiple paydays during organizing campaigns, but crew members still made huge sacrifices in terms of lost wages. For many strikers, increasing doubt over what the future held for them proved as painful as the interruption of their paychecks. Would their strike succeed? Would Bravo cancel Shahs? Would scabs replace them to finish the season? The longer the strike dragged on with no substantive negotiations, the more anxieties mounted.

Photo by Sara Terry

On September 25, the employer illegally declared that the strikers no longer had jobs to which they could return. Then the battle for Shahs became a war over employees’ fundamental right to stand up and stand together to demand better of their employers. “If Bravo or Ryan Seacrest thinks that their problems go away because they announce that our editors have been fired, they’re sorely mistaken,” declared Editors Guild President Alan Heim, ACE. “This is no longer just a fight about whether this crew gets health and retirement benefits; it’s an unabashed attack on the right to organize. We will fight back and we will win. No self-respecting editors are going to cut this show after this show cut their colleagues.”

Had our adversaries thought they could wear us down with their intractability, they miscalculated. Over the span of 30 days, hundreds of picketers walked more than 3,000 miles collectively. We carried the fight from Miracle Mile to Rockefeller Center, where scores of New York union members and allies rallied outside the corporate headquarters of Bravo and NBC Universal. Hundreds more converged on Universal Studios to make clear that the entire company would be held accountable for its subsidiary’s attack upon employees’ basic rights under the law. With each day’s delay, the community rallying to the support of our strikers only grew angrier and more committed.

Facing a barrage of bad publicity, skewering on social media, pending charges before the National Labor Relations Board, pressure on the network’s advertisers, promises of escalation and, ultimately, the impossibility of completing work on the show without a union agreement, the employer eventually relented. On October 10, exactly one month after the walkout began, we reached an agreement to return folks to work under an IATSE contract. The win came at a great cost, but our solidarity ultimately trumped their stubbornness.

As I write this, the Shahs victory is still fresh; we will require more time to extract from this experience all the lessons it might yield to inform our future organizing. But the strike affords one clear lesson for those who oppose our organizing: They can run down the clock, but they can’t turn back time.

Our solidarity is neither a short-lived nor a fair-weather phenomenon. It’s what we believe. It’s who we are. We have the strength to hit hard, and the cohesion to withstand punishment. Together, we win.