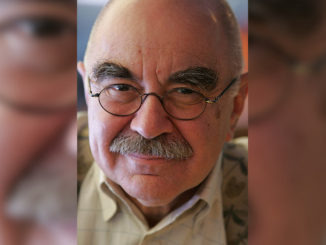

by Michael Kunkes • portraits by Gregory Schwartz

The crack of Indiana Jones’ whip, the roar of an Imperial TIE fighter, the hum and crackle of clashing lightsabers, the voice of Wall-E speaking through his circuitry… Almost anyone who has come of movie-going age in the past 30 years knows these sounds; they are part of worldwide pop culture. And all can be traced to the same source: sound designer extraordinaire Ben Burtt.

In 1976, Burtt was working alone in his makeshift sound lab in George Lucas’ San Anselmo, California house, a building known simply as “Parkway”—which served as the first headquarters of Lucasfilm. The year before, just after finishing his master’s degree in film production at the USC School of Cinema masters degree program, Burtt was hired to record sounds for a new Lucasfilm project with a working title of The Star Wars, replacing Walter Murch, A.C.E., MPSE, CAS, who was unavailable at the time. Surrounded by reel-to-reel multi-track tape recorders and an eclectic collection of mechanical and audio devices, he was turning his recordings of bear and other animal voicings into the tonalities of a Wookie called Chewbacca, speeding up Zulu recordings to create Jawa voices, blending the electric hum of an old TV set with the sound of a 35mm projector into the iconic sound of a lightsaber, and providing his own vocalizations to help create the voices of R2D2 and Darth Vader.

By the time the movie was finished in 1977, The Star Wars had become Star Wars, and the “new Walter Murch” had morphed into the first Ben Burtt, contributing his lifelong passion for collecting and building sounds to an emerging film language that would soon formally come to be known as sound design. It’s a language that Burtt once said has been evolving since The Adventures of Don Juan (Warner Bros., 1926), a silent film with a Vitaphone orchestra and the rudimentary sound effects of a sword fight.

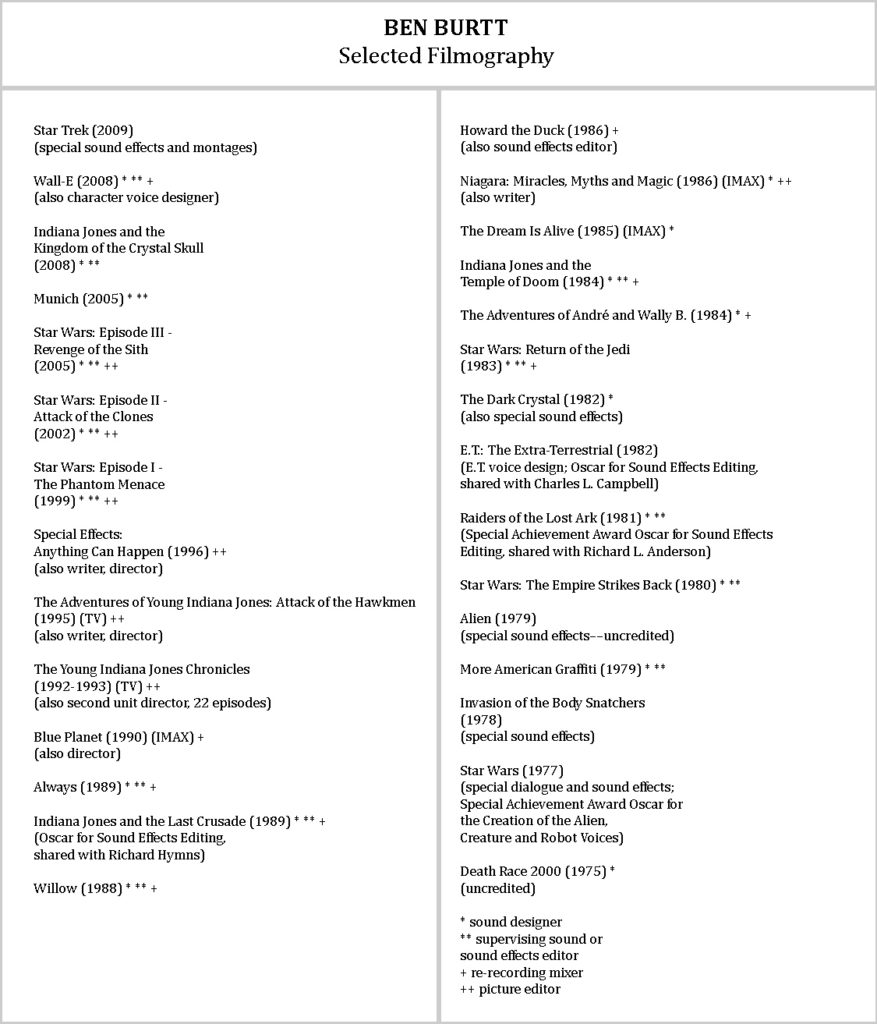

More than three decades after Star Wars changed the face of fantasy and space opera forever, Burtt is again working in solitary fashion––this time on an undisclosed project in a much higher-tech facility at Disney/Pixar, but his methodology has not changed. “I’m sitting at my computer with sounds that are waiting to be made into something; I just don’t know what it is yet,” the four-time Oscar winner says with a laugh. His body of work in sound effects and sound design, largely accomplished at Skywalker Sound in Marin County, California, has enhanced over 40 motion pictures, TV series and documentaries. In his own quest to become a more complete filmmaker, Burtt has also by turns been a producer, director, writer, re-recording mixer and picture editor–– most notably on the second trilogy (or is it the first?) of the Star Wars franchise.

But it is his pioneering work in gathering organic sounds (natural, mechanical and sometimes musical), then customizing them into a performance that fits the meaning and action of a film, that has helped forge an iconic cinema aesthetic in much the same way the Golden Age of radio utilized sound effects to make an audience sit up, listen and listen hard.

Burtt spoke with CineMontage on the eve of the May 8 release of his latest project, Paramount Pictures’ Star Trek, directed by J.J. Abrams.

CineMontage: You are the first person, along with Walter Murch, to be credited with the title of sound designer. How did that come about in your case?

Ben Burtt: On Star Wars, I was recording and editing sounds, doing temp mixing and pre-mixes, and creating special dialogue––which was unusual at the time. There was discussion as to what title could apply to this odd, hybrid job that was crossing all the traditional barriers, combining the jobs of recordist, sound editor and mixer. On Star Wars, my credit became: “Creature and Robot Voices Created by Ben Burtt.”

The first time the title of sound designer was applied to me was when I did More American Graffiti [the same year Murch received that credit on Apocalypse Now]. It’s a title that is still unofficial and unrecognized by the Academy, but in Northern California we felt freer to create titles because there was less adherence to the existing traditions. I didn’t invent it; it was something that I believe George Lucas and Gary Kurtz came up with.

CM: How do you define the position?

BB: In some cases, a sound designer might invent a few specific sounds, turn them over to the editors and not necessarily be working with the director or imposing a signature on the entire movie. But at the other end of the scale, there are those like myself who are an influence all through pre-production, production and post. That kind of sound design is way more comprehensive because you are being asked to render a lot of creative contributions. That’s why it’s hard for the Academy to define sound designers, because the work varies so much from picture to picture. What we do is dictated by the unique needs of each production.

CM: How did Skywalker Sound evolve?

BB: When Star Wars was completed, the sound department at Sprocket Systems (the original name of Skywalker Sound) was two people: myself and Howie Hammerman, the engineer. The joke was that I would break the equipment and he would fix it. We began to grow as Lucasfilm got involved in multiple productions. In 1982, we moved into the ILM Kerner complex in San Rafael and opened our first mix room, Mix A, so that we could mix on our own. In 1987, we moved to the ranch near Nicasio. The original idea behind Skywalker Ranch was that George would have five films concurrently in some stage of production. When it became clear that wasn’t going to happen, Sprocket Systems opened itself to outside clients and eventually was renamed Skywalker Sound.

1. Helium canister used for pitching up human voices into alien voices for Star Wars’ cantina scene.

2. Original Nagra stereo tape recorder used for field recording on Star Wars and all Indiana Jones movies.

3. Reel-to-reel recorder, Burtt’s main pre-digital tool in recording and sound editing.

4. R2D2 placard used to advertise Burtt’s use of Teac tape recorders.

5. Air conditioner cushion springs from roof at Pixar; used for sound of clanging swords.

6. Jumpsuit made to wear while recording sound effects for Return of the Jedi.

7. Mini-Moog synthesizer used for creating electronic tonalities of space in both Star Trek and Star Wars.

8. Custom-built arrows used to reproduce the sounds from Warner Bros.’ 1938 version of The Adventures of Robin Hood.

9. ARP 2600 synthesizer used to record R2D2’s voice.

10. Electric motor used to spin rods to

create wind sound.

11. Ice cube tray used for C3PO Foley arm movements.

CM: Who have been your mentors in sound design?

BB: First, there was Murray Spivak at RKO [co-winner of the 1969 Best Sound Oscar for Hello Dolly!], who created the sound effects for the original King Kong in 1933. His work in King Kong was the beginning of sound design for fantasy motion pictures. The voice of Kong, the sounds of the jungle, the creatures, and the screams—all were individually created and nothing like it existed before. He was able to mix two, perhaps three tracks together at a time, using two optical playback machines, making a loop and blending things together. When people make monster movies today, they still don’t gravitate far from those principles and techniques.

Then there is Treg Brown, credited as the editor of the Warner Bros. cartoons from 1933 to 1966. He also created all the sound effects. He was a huge influence on me, because he used real sound effects for comic purposes and for exaggeration. The Road Runner is made from the sounds of high-speed aircraft. If Wile E. Coyote crashed into something, the impact wasn’t the sound of a cymbal crash or a bass drum hit; it was Treg Brown cutting in a thunderclap and a destroyer alert siren. Associating these real-world sounds with the events in the cartoon made the action seem all the more realistic and melodramatic. I found this same approach gave dramatic credibility to the fantasy film. For me, Star Wars was one gigantic Warner Bros. cartoon.

A third major influence was Jimmy MacDonald at Disney, who I once had the chance to meet when I was just out of school. He was a master at building props that were used to actually “perform” sounds for specific characters, such as a talking bee or a singing frog––or the sound of Mickey Mouse’s car with all its voice-like rhythms and percussions. [MacDonald was also the voice of Mickey Mouse and, like Burtt, was a drummer.] What was so effective about his work over 40 years at Disney was that he was a performer and, like a musician, performed the sounds that he built. The end result was something that came out of his soul as a musician. My best sounds have usually been the result of some sort of interactive performance with a prop or technology.

CM: How have these people influenced your own approach?

BB: It’s all part of what I call the “language” of sound effects. As a sound designer, it’s to your benefit to understand what came before you, because audiences are somewhat conditioned by those traditions. That way, when you go to create a new monster or spaceship sound, you don’t have to imitate what came before, but you can come up with something brand new that builds on the past. For me, one of the things that is most exciting about sound design right now is the interface between our brains and our sound effects libraries. For example, I discovered on Wall-E that I could do things like using a light pen and tablet to trigger sounds and alter their pitch by “performing” with my hands. That’s something MacDonald might have done––build a device that allows you to perform a sound. That is so important, because it allows you to inject a performance, to use your own sense of musical timing and control the texture of a sound. That’s an advantage we have today that Spivak or Brown never had.

CM: What makes a successful sound designer?

BB: It boils down to the ability to select or create the right sound for the right moment, to pick the thing that dramatically tells what needs to be said in that moment. That applies to dialogue, music or sound effects. I don’t think successful sound design has ever been about the quantity of sound or how many tracks you can use at once. We all know that there are real limits to that. We suffer nowadays from too many films being filled with noise––partly because the technology has made it so easy to pile things on. I have to constantly re-learn the lesson of subtractive rather than additive sound orchestration.

CM: How can sound design provide more bang for the buck in smaller movies?

BB: You can do so much to color in the drama of a movie with sound without hiring a giant crew. The technology now is efficient enough that you can do a great deal of work on your laptop. When I was cutting Star Wars: Episode III, I was sitting at an Avid where I was editing picture. I could turn my chair to the left, where there was a laptop connected to my library with a mini-keyboard so I could do quick sound design. I also had a mic with which I could record my voice for something temporary and export that into the Avid to try against picture. Then I could turn to my right, where I had another computer that had CG models of the main characters, vehicles and environments. I could do simple, limited animations of a ship going toward a star field or put an image of a CG character into an environment. I could choose a camera angle, lens focal length and movements.

These animatics became the guide from which to develop new shots as we went along. The upshot of this is that there are desktop tools available for one editor to tackle a wide range of sound and picture editing tasks. Whether you are doing “tentpole” or “pup tent” movies, the editor today has some very economical and powerful tools at his command.

CM: How did you come to work on the new Star Trek?

BB: In October 2008, I was invited by J.J. Abrams to come to a screening, and perhaps offer some advice. They were searching for sound effects with a distinctive signature that also indicated the best way to orchestrate the density of sound effects, music and dialogue that the film demanded. I started to feed them some ideas, and that led to, “Can you make things for us?” So, in a series of steps, I came on board and ended up creating a library of almost 400 sound effects, as well as designing and pre-mixing certain key seq-uences from bottom to top. My credit on the movie became “Special Sound Effects and Mon-tages,” which was the best way I could sort of fit myself in.

CM: What is your personal re-lationship with the whole Star Trek zeitgeist?

BB: You might say I’m a longtime “latent trekkie.” When the show came out in 1966, I was a freshman at Allegheny College––and we had no TV reception, believe it or not. I would have my father record the shows on reel-to-reel audio tapes and send them to me. I listened to the first eight episodes before I ever saw the show. That’s how I came to love the sound effects on that first series; they were so well done that they fired up my imagination and brought the show to life.

CM: How did your work on the new Star Trek movie pay homage to the original series?

BB: The supervising sound editor on the original series was Douglas Grindstaff [see sidebar, page 30] and, with the urging of Gene Roddenberry, he and his team really raised the bar and did some things that no one had ever done before in science fiction. They articulated sounds for the entire ship––every room sounded different, and every piece of equipment had a unique sound to it. Secondly, they used real motors and radio sounds, to give it a sense of reality, but also a lot of musical sounds and tones. If someone pressed a button on a console, it made a little musical melody. There was sensitivity to making things that had an emotional feel to them, and the detail they went into was unprecedented. I carried those methods into my work on the first Star Wars movie, and that guided a lot of my thinking when I began creating sounds for Star Trek.

CM: Why did it take nearly 30 years for you to work on a Star Trek movie?

BB: I was on staff at Lucasfilm during a lot of that era and was completely wrapped up in Star Wars, so the space in my life for space was already completely filled!

GM: What challenges did working on the new film present?

BB: It was very unusual for me to be on a movie that was not in flux visually. I am used to starting even before shooting begins so that I can build up a library and be on hand during picture editing. This way I can inject ideas and do R&D as I go along to make decisions about what will and won’t work. On Star Trek, this process had to be cosmically compressed. However, it was very exciting because the picture was complete and everyone could focus creative attention on sound. We didn’t have to contend with the usual disruptions of picture changes and incomplete visual effects. Otherwise, I don’t think I could have created and pre-mixed 400 sounds in just six weeks.

CM: What was your mission during the time you were on the movie?

BB: I was interested in making two things happen. One was to make the film sound like a classic science-fiction movie–– which means addressing a legacy that goes back to the beginning of the genre. Secondly, to attach it specifically to what I loved about the original TV series. I was interested in making sounds using some of the same techniques that may have been used in the ‘60s. It meant going back to things like test oscillators, spring reverb chambers, feedback and mechanical sounds. I wanted to recapture the sense of sound effects done with a musical sensitivity. I wanted to not only pay homage, but to expand and translate those original concepts into something grander and more powerful.

CM: What was your interaction with director J.J. Abrams?

BB: I would have sessions with him on a daily basis. I would audition sounds in context with dialogue and music. Once he was satisfied with the direction of a sequence, I would pre-mix it, and pass along additional sounds to supervising sound editor Mark P. Stoeckinger. We would all review it in the mix with re-recording mixers Paul Massey, Andy Nelson and Anna Behlmer. J.J. would make the final decisions on balance.

CM: What did you bring from your experience in Wall-E to Star Trek?

BB: Like Wall-E, Star Trek is a movie jammed with sound, and it brings to the forefront the whole challenge of orchestration, of picking the right set of sounds for any given moment. Also like Wall-E, Star Trek is a very fast-paced movie. You can design sounds that might be interesting, but shots go by so quickly—40 frames here, 28 frames there––that by the time you hear something, the shot’s already gone. The sonic density of Wall-E forced me every day to weed out and orchestrate sounds so that they went well together.

When I came to work on Star Trek, which is a hyperactive movie in its own right, I was able to turn to J.J. and say, “I know there’s two dozen things happening in this shot, but we have to decide what we want to hear; maybe only two well-placed sounds will deliver the goods for that shot.” A lot of the discussions in the final mix were about that. You don’t just want a wall of noise. What you want to hear are the specific notes and melodies of sound effects, dialogue and music, each having its own turn as the main “theme.” You have to carefully weed through and pick the right things, and Wall-E helped me get better at that.

Copyright 2008 by Paramount Pictures. All Rights Reserved.

CM: What do you think is the future of sound design?

BB: I don’t think that audio creation technology has kept up the pace with what we do visually. There’s a whole new set of tools waiting to be built that will allow us to create, alter and mix sound effects and voices with results that have never been heard before. If they can make Brad Pitt appear to be 17 as in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, then there must be potential means of synthesizing and manipulating audio to create exciting new worlds of sound. I’d love to be able to do more of that.

CM: What are the best creative moments for you?

BB: For me, it’s the simple things. When I was doing Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, I was looking for sounds for the skulls, some magnetic effects and unseen telekinetic forces. Then one night, I was walking out to my car, when my attention was drawn to the buzzing sound of a mercury vapor lamp in the Skywalker parking lot. I recorded it, slowed it down, played it backwards, and put it all over my keyboard. I got so much mileage from that one little buzzing sound which seemed to fit the bill.

On Star Trek, creating a two-second gap of silence, then adding a backwards feedback “shimmer” gave dynamics and accent to a supernova explosion. On Wall-E, a quiet moment with nothing heard but Wall-E’s fire extinguisher propulsion in space was audio poetry to me. Once again, it was all about finding the right component, keeping it simple, and finding something emotional.

CM: What part of the process do you like best?

BB: The thing I love most is the moment I put sound or music in for the first time against a picture that previously had nothing playing with it. I get the same charge doing this as I did when I was a kid putting sound against my silent home movies. That moment is like giving birth to something, and it is part of the thrill of participating in the magic of the movies.

Editor’s Note: More of this interview with Ben Burtt, including outtakes from this article, can be found on www.editorsguild.com.