By Betsy A. McLane

A disconcerting sense of melancholic nostalgia ties together two very different new books. The authors write about Hollywood’s past, and despite moments of fun, both books recall worlds of moviemaking now long lost.

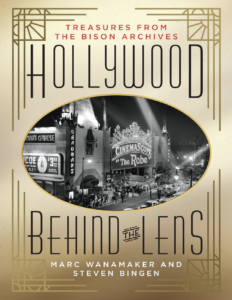

“Dorothy Parker in Hollywood” by Gail Crowther and “Hollywood Behind the Lens: Treasures from the Bison Archives” by Marc Wanamaker and Steven Bingen contain classic Hollywood stories of rousing success followed by fading glamour. Crowther’s is a skillfully researched biographical narrative with only one photograph, on the cover. Wanamaker/Bingen’s is similarly fact-filled, but consists almost entirely of photographs. It is one of Wanamaker’s series of more than 20 remarkable Southern California picture books. While neither is a seamy expose, nor a work of great tragedy, their subjects — portraits of bygone days — seem similarly, and sadly, quaint. The aura of wistfulness on their pages goes deeper than simply the word “Hollywood” in their titles.

For those who care about Hollywood history, both Marc Wanamaker and Dorothy Parker are names with resonance. While Parker holds a solid place in the pantheon of 20th century American literature, and Wanamaker’s renown is limited to a much smaller group of cognoscenti, each in their own way is legendary. On Wikipedia, he is described as “Marc Norman Wanamaker (born October 1, 1947, in Los Angeles)” who “is the founder of Bison Archives, which manages research on the motion picture industry.” Mrs. Parker’s entry states, “Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet and writer of fiction, plays and screenplays based in New York; she was known for her caustic wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.” Each of these descriptions are understatements. Wanamaker’s work is central to preserving how Hollywood looked and worked; Parker’s lets readers in on elite American urban life from the 1920s to the early 1940s.

For those who care about Hollywood history, both Marc Wanamaker and Dorothy Parker are names with resonance. While Parker holds a solid place in the pantheon of 20th century American literature, and Wanamaker’s renown is limited to a much smaller group of cognoscenti, each in their own way is legendary. On Wikipedia, he is described as “Marc Norman Wanamaker (born October 1, 1947, in Los Angeles)” who “is the founder of Bison Archives, which manages research on the motion picture industry.” Mrs. Parker’s entry states, “Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild; August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967) was an American poet and writer of fiction, plays and screenplays based in New York; she was known for her caustic wisecracks, and eye for 20th-century urban foibles.” Each of these descriptions are understatements. Wanamaker’s work is central to preserving how Hollywood looked and worked; Parker’s lets readers in on elite American urban life from the 1920s to the early 1940s.

A great deal has already been said about Parker. There is a documentary, “The Ten Year Lunch: Wits and Legends of the Algonquin Round Table” (1984) directed by Aviva Slesin, and a fiction feature, “Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle” (1994) directed by Alan Rudolph and starring Jennifer Jason Leigh, about aspects of Dorothy Parker’s life. There are many books and essays about her work, which continues to be popular today. “Dorothy Parker in Hollywood” is, however, the first book-length attempt to dissect Parker’s writing for the movies. Wanamaker’s personal life has not been profiled, but he is well known to everyone who wants to learn about behind-the-scenes Hollywood history. His Bison Archives collection includes tens of thousands of photographs, many very rare, and is now housed at the Margaret Herrick Library of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These are distinctly different books, but if the reader looks closely, Wanamaker and Bingen offer a visual backdrop for the story Crowther tells.

When “talking pictures” took over in the early 1930s, Dorothy Parker was one of the many writers recruited by film studios to meet the needs of sound. Particularly, producers wanted people who could write dialogue, and Parker was noted for her quips and quotes. Her poems and short stories were known for just the sort of snappy one liners and barbed observations that could make a movie worth listening to. Such is the poem “Learning from Experience”:

By the time you swear you’re his, Shivering and sighing.

And he vows his passion is Infinite, undying-

Lady make a note of this:

One of you is lying.

She was also known for the devastating verbal barbs she shot at everyone she knew. These became particularly cruel when Parker drank a lot, which was almost daily. She often later regretted the pain her words inflicted, but remorse did not stop her drinking nor her attacks.

The current book details many of Parker’s drunken episodes in Los Angeles and their ugly day-after consequences. (The book’s descriptions of night life at the Coconut Grove of the Ambassador Hotel are mirrored in photographs in “Hollywood Behind the Lens.”) Crowther attempts to analyze the reasons Parker drank. These are difficult to ascertain since, other than what can be gleaned from her public writing, there is almost no record of Parker’s BOOK REVIEW feelings. She destroyed her letters and memorabilia before her death, so Crowther was forced to rely on accounts from others, public records, and observations about the way contemporary society viewed a very successful woman writer. In Dorothy Parker’s case, that was with alarm.

Alcoholism in women was little discussed in the first half of the 20th century, and probably because her romantic partners and other people in her social circles also drank heavily, and she produced quality work that made money, few people confronted her. Crowther attributes Parker’s misbehavior to her deep-seated insecurity and dependence on good-looking men. The book emphasizes Parker’s tremendous lack of self-confidence, reiterating the ways she minimized and demeaned her own writing. The melancholia rises from reading about how this small, brilliant, and successful woman despised herself. Crowther captures this fascinating story beautifully. Parker was famous; her books always sold well, and she was a star at the infamous cocktail-fueled literary lunches in the Rose Room of New York’s Algonquin Hotel.

Parker was a darling of that city’s Roaring ‘20s café society and her name carried the kind of prestige that Hollywood was buying in the early 1930s. Like many writers, including her dear friend and Algonquin lunchmate Robert Benchley, she was persuaded to move west by the large salary the studios offered. In 1937, she and her writing partner (and husband) Alan Campbell were making a joint salary of $5000 a week.

Even so, Parker notoriously hated Hollywood, stating, “I can’t talk about Hollywood. It was a horror to me when I was there and it’s a horror to look back on. I can’t imagine how I did it. When I got away from it, I couldn’t even refer to the place by name. ‘Out there,’ I called it.” Like some of the other literary figures of the 1920s — Scott Fitzgerald, Nathaniel West, and John Howard Lawson — Parker had a push-pull relationship with the studios, despite the fact that it was the film work that made them rich, at least temporarily. Parker’s finances were generally a mess. She made big money, and she spent lavishly on herself and on the social causes that were vital to her. She was ardent in donating money for causes that helped poor and disenfranchised people, was active in reinvigorating the Writers Guild of America in the 1930s, and even journeyed to Spain in support of the Popular Front in the Spanish Civil War. According to Crowther, Parker felt that there was no irony in living a luxurious lifestyle as long as she supported, both with money and her presence, the political causes in which she believed. Her left-leaning activism later made her the target of anti-Communist investigations, but she was spared the worst of the blacklist horrors.

Although closely identified with New York, Parker was peripatetic for much of her life. Crowther documents the many moves that Parker made among Hollywood, New York City, Europe, and a farm she and Alan Campbell purchased in Pennsylvania. Crowther’s excellent research gives careful attention to the many places Parker lived while in Los Angeles. Apparently, she never found a house there that suited her. Especially interesting are descriptions of Parker’s first Los Angeles residence, the fabled Garden of Allah on the Sunset Strip, where Parker and her husband joined the rowdy nightly parties in Robert Benchley’s bungalow. There her behavior was watched and written about by nationally syndicated gossip columnists, including Scott Fitzgerald’s lover, Sheilah Graham. Crowther quotes Graham about Parker, “She was the most unpredictable woman I ever met in my life….I realize that she was a very unhappy woman. She inhabited a vale of tears, and the only way she could live with herself was to murder everyone else with her biting word.”

“Hollywood Behind the Lens” gives a good sense of that area of the Strip in a 1938 photo of Schwab’s Drugstore which was across Crescent Heights Blvd. from The Garden of Allah. This spot supplied much of the liquor and food to residents of The Garden of Allah, as it later did for the Chateau Marmont, which was built down the street from Schwab’s.

Parsing what Parker contributed to films is as difficult as pinning down her true motivations. That she contributed is certain; she earned 32 screen credits and was involved, uncredited, with at least six more releases. She and Campbell received an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay Adaptation (from 1932’s “What Price Hollywood”) for “A Star is Born” (1937), directed by William Wellman who shared with Robert Carson the Oscar for Best Original Story. Carson was also credited as a writer of the screenplay, and it is this mish-mash in the studio system way of treating writers that, among other frustrations, infuriated many of them.

Gail Crowther’s research is thorough, backed by many footnotes and an extensive bibliography, but her book disappoints in its lack of film analysis. Even though it can be almost impossible to pin down which writer (or producer or director) wrote what for the studio films of this era, there could have been significantly more mention of the acting, directing, editing, studio style, sound or financial and critical results of the pictures.

In contrast, Wanamaker and Bingen’s book is all about how films use tricks and illusions to make magic. For example, Margot Kidder and Christopher Reeve are seen mounted on the apparatus that made Superman “fly.”

Crowther does pinpoint some pithy dialogue as Parker’s, and she discusses how Parker and Campbell worked as a team, but this book’s focus is on Dorothy Parker, the woman. Crowther’s most revealing image of Hollywood is her beguiling description of a studio’s male-dominated writers meeting where Parker — hired as the great New York wit — sits knitting.

Parker is a lasting literary trope in American culture. Even in November 2024, The New Yorker published this derogatory view of Parker’s time in Hollywood: “Despite her best efforts to kill a successful writing career with booze and Hollywood, Parker’s legacy is also like that of the Arizona (the USS memorial at Pearl Harbor): enduring, grand, and forever leaking into the shallow waters of other people’s prose.”

Wanamaker’s life work is the opposite; he collects the bits and pieces that leaked out of Hollywood over the past 100 years and preserves them, allowing them to be repurposed and studied. In this way, his contribution to understanding American popular culture can be seen to be as valuable as Parker’s writing. Each witnesses the triumphs, tragedies, and farces of the past century.

But despite the silly sight of Steven Spielberg posing in the jaws of his mechanical shark, and the perky irony of the Los Angeles Times in 1934 calling Parker “the most dangerous woman in the country,” these books are poignant. The brightest thing in both is the presence of the carbon arc of a kleig light, a brilliance that is lost in today’s glare of endlessly streaming content and AI immersion in places like the Las Vegas Sphere.

Hollywood Behind the Lense: Treasures

from the Bison Archives: By Marc Wanamaker and Steven Bingen – 226 pages – Roman and Littlefield Publishing, 2024

Dorothy Parker in Hollywood – By Gail Crowther – 291 pages – Gallery Books, 2024 Betsy A. McLane is a freelance writer

and expert on documentary films.