by Michael Kunkes • Portraits by Gregory Schwartz

The ongoing fascination with the War Between the States seems endless. No conflict in American history has been so broadly examined through the personal experiences of participants, journalists and observers, nor so dramatized through motion pictures and books both fiction and non-fiction—all in an attempt to bring an understanding of why it all happened, and the lessons it contains for Americans to this day.

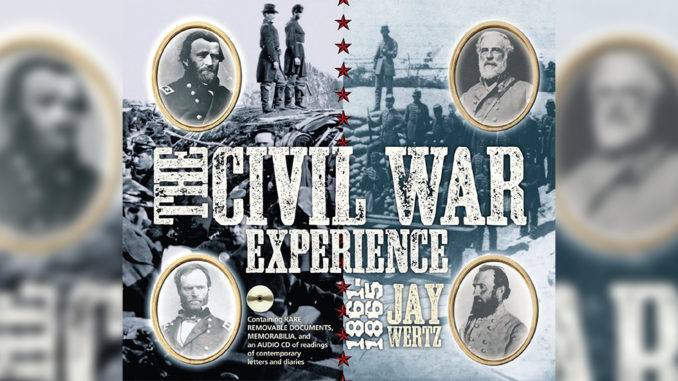

Now, in The Civil War Experience: 1861-1865, published by Random House imprint Presidio Press, (ISBN 0-89141-882-2, $50.00), Jay Wertz has created a lavish and richly detailed yet easily digestible combination of words and pictures exploring every major event, irony and human drama of what has often been called the first modern war. The book features 30 removable facsimilies of vintage documents, 200 specially chosen photographs and 19 full-color campaign maps with legends.

With his upbringing, it’s hard to imagine Wertz, a picture and sound editor, having a passion for anything else. Born in Hanover, Pennsylvania, the site of a cavalry battle that preceded the Battle of Gettysburg, he played as a boy in that battlefield’s Devil’s Den before he even knew the true significance of the place. In 1963, the battle’s 100th anniversary, he participated in his Civil War re-enactment, as a member of the North-South Skirmish Association. If he wasn’t hooked on the Civil War before, that experience sealed it.

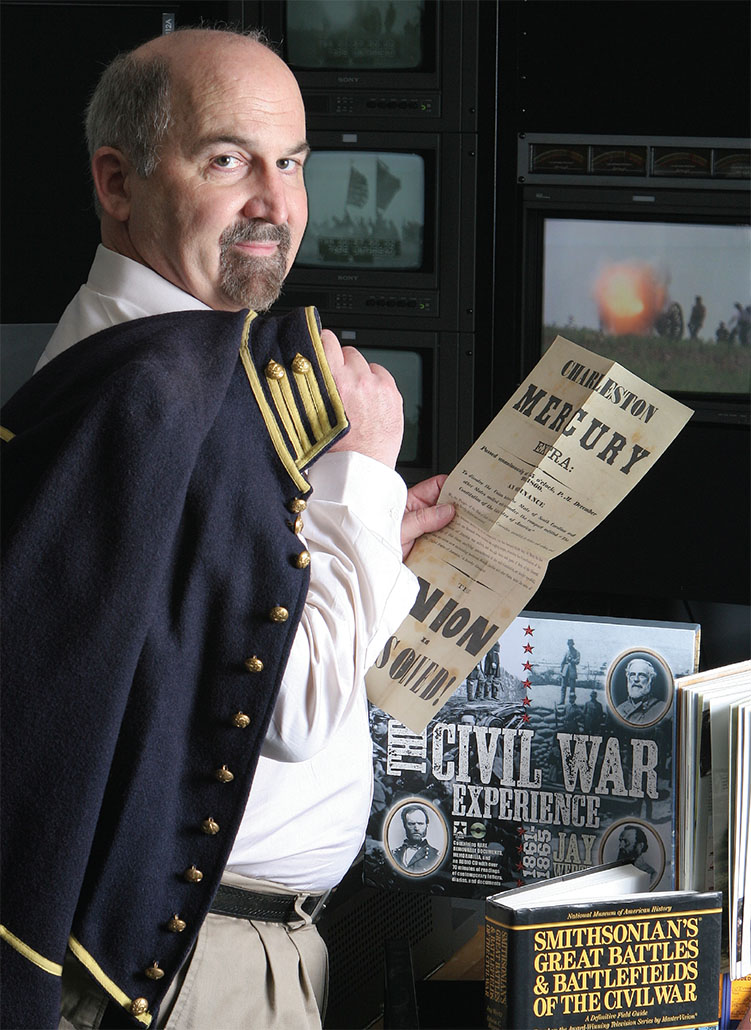

Wertz, who makes his home in San Diego, has had two careers––and they have merged into each other over time. A Guild member since 1977 with over 700 writing, editing, producing and directing credits, he has called Paramount Studios home for over 21 years. He’s been a segment editor on Entertainment Tonight, and currently works in the Paramount Technical Operations department, re-cutting material for secondary and tertiary markets, including airline, DVD, broadcast, syndication and barter, on shows from Star Trek to Frasier to The Godfather. As a sound editor in 1980, he was nominated for a Best Sound Oscar for Ken Russell’s Altered States, directed the feature Ninja Nightmare and created a CMX-style multi-camera linear video editing system that was used briefly on 1985’s Rocky IV.

In 1994, Wertz wrote, directed and edited, as well as produced The Learning Channel’s Great Battles of the Civil War, a Telly Award-winning, nine-hour series that called on extensive, accurate re-enactments and featured the voice talents of Charlton Heston, Richard Dreyfuss, Burt Reynolds, Dennis Weaver, Ossie Davis, Burgess Meredith and Trish Van Devere. Though it aired some four years after Ken Burns’ epic PBS series, The Civil War, Wertz’s efforts to bring a Civil War series to the airwaves actually go back almost 30 years, when Pennzoil almost picked up the idea (along with his produced footage) for—of all things—its Action-makers sports series.

An admirer of the awareness that the award-winning PBS miniseries brought to the conflict for millions of Americans, Wertz nevertheless feels that Burns’ effort tended to latch onto certain points of view at the expense of others. For Great Battles, Wertz operated without much of a budget, but also without a lot of constraints. “I did what I wanted to do, but also listened to the opinions of a lot of people and didn’t go in with any pre-supposed notions,” he explains. “Some people are turned off by re-enactments, but I still believe they are the best way to give accurate perspective to what life was like back then.”

In 1997, Wertz collaborated with Ed Bearss, former National Park Service Chief Historian, and published Smithsonian’s Great Battles and Battlefields of the Civil War, a book companion to the TV series. A field guide that organizes the battles by the states in which they took place, the book is a cross-referenced travel guide that allows readers to follow recommended driving tour itineraries or flip ahead to the next sequential battle in a campaign. In addition to detailing each site’s attractions, the volume also features detailed maps and notes travel amenities such as handicapped access.

What truly gives the 65-page, large-format The Civil War Experience its color and lushness, as well as sets it apart from other books on the subject, are the removable enclosures inserted into nearly every chapter. With the exception of just one topographical map of the Shenandoah Valley, each document is reproduced at its actual size. Wertz included many key documents that might be expected, especially Lincoln’s final draft of the Gettysburg address, but there’s a wealth of more previously unseen material.

Included is a telegram informing the US Secretary of War of the surrender of Fort Sumter in April 1861; Robert E. Lee’s letter of resignation from the Union army; a letter from a Union prisoner in the notor-ious Andersonville prison camp to his wife, a tongue-in-cheek newspaper published by Confederate prisoners at the Union prison at Fort Delaware, a letter from Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson to the Governor of Virginia, and the articles of the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. There is also an audio CD of readings of memoirs and documents.

“We are blessed in this country because we do have a lot of repositories for documents, both government and private,” Wertz says. “Even though the digital age makes things more easily accessible, you still have to know where to go to get things. We tried to obtain as broad a cross-section of materials as we could of Civil War life, through diaries, personal letters, government orders—even a prison newspaper, which my sister found at the New York Historical Society.”

The biggest challenge for the author was to provide a narrative of the Civil War that would be detailed enough for those who knew something about the war, and yet accessible enough for readers who might be picking up their first Civil War book, attracted by the memorabilia and the packaging. “The angst came from having to eliminate things that were significant and that I felt were important, but there wasn’t enough space to accommodate them,” Wertz muses. “But it has enough to provide something for everybody.”

Since the original copies of most, if not all, of the book’s enclosed documents are locked away in vaults and may never be handled by humans again, exact reproduction of documents proved to be a bit of a guessing game. “Because the Lincoln papers in the Library of Congress are so voluminous, someone in the 1950s decided to preserve them on black and white microfilm rather than color,” Wertz explains. “We actually had to call in some Lincoln experts for some high-level opinions on what color ink he used, and the quality of the paper he wrote on.

Wertz has strong opinions on Hollywood’s treatment of the Civil War. “Most of the work that has been done lately is great,” he says. “I loved Glory (the attack on Fort Wagner receives a prominent mention in his book), but Ron Maxwell’s Gettysburg and Gods and Generals both tried to bite off a little too much. I also loved John Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage and Don Siegel’s The Beguiled.” He also postulates that some of the best films with Civil War characters such as Sam Pekinpah’s Major Dundee and John Ford’s The Searchers, take place after the war’s end. “The Civil War is just plain good fodder for movies,” he adds. “And as far as the Hollywood line that you can’t make money on a period piece, well, that depends on the period and the piece.”

Has the author’s day job as an editor helped his experience as a writer of books? “Taking that idea and applying it to non-fiction writers? Most definitely, Wertz asserts. “There’s the old saying that editors make the best directors. Well, just like an editor, a history writer has to know what works and what doesn’t, must have a sense of pacing and rhythm, must be able to concentrate on what is important—and make it all work together.”

Wertz is already planning his next book, an expansive history in a similar format that will encompass the Conquistadors and the discovery of Alaska, as well as the more familiar periods of the American West. “A lot of people talk about the coming obsolescence of the printed word; that just isn’t going to happen,” he concludes. “However, we do have to find new and challenging ways to attract an audience that seems to be much happier watching than reading.