A new book finds ‘hidden figures’ at Disney’s studio, and beyond

By Betsy A. McLane

Cinderella, Snow White, Ariel, Mulan, and Belle may be Disney’s star princesses, but the queens behind their animation are real-life women. Grace Huntington, Sylvia Holland, Bianca Majolie, Retta Scott, Gyo Fujikawa, and Mary Blair are not likely to be associated with the successes of Disney Studios, but Nathalia Holt’s “The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women Who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History” changes that. In this absorbing book, these and other women take their place alongside the most famous Disney writers and animators, including the group referred to by Walt as his “Nine Old Men.” Holt gives readers an overdue revision of accepted Disney history, bringing to light information and insight that changes the accepted history of animation.

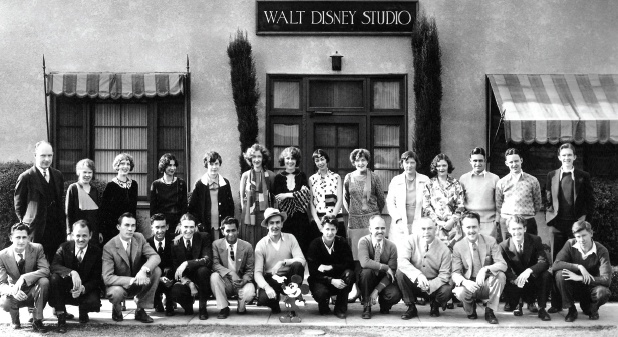

It is well known that Disney employed many women in the Ink and Paint Department. Beginning in 1923 and into the 1960s, up to 100 young women at a time worked long hours to outline and color animators’ original line drawings. They used paints uniquely formulated in the studio’s labs to make Disney’s iconic characters sparkle in the way Walt envisioned. Thousands upon thousands of individual cells show the results of their delicate, white-gloved artistry. Women were not, however, welcomed in major creative departments. A studio form letter once mailed to any woman who applied for a job stated: “The only work open to women consists of tracing the characters on clear celluloid sheets with India ink and filling in the tracings on the reverse side with paint according to directions.”

Holt’s groundbreaking book traces the progress of the few who made it into the rarified writers’ and character animators’ circles. She illuminates not only their work at the studio, but their backgrounds and personal lives. Perhaps only a female writer could tell their stories truly. The author’s perspective is made clear in the Epilogue by a story Holt tells her 5-year-old daughter on their trip to Disneyland. There, as they glide through the perennially popular “It’s a Small World” ride, Holt explains, “’Do you see that doll up there by the Eiffel Tower? ‘The one holding the red balloon?,’ the child cries excitedly.’ ‘Yes, that one, with the short blonde hair,’ I say. ‘That’s Mary Blair. She made this ride.’”

Holt backs up this personal approach with impressive original research throughout “Queens of Animation,” as she did in her 2016 bestseller “Rise of the Rocket Girls: The Women Who Propelled Us, from Missiles to the Moon to Mars.” She conducted detailed interviews with surviving family and friends, scoured press clippings, and pored through letters in which these women revealed their thoughts and feelings, as well as their experiences at Disney Studios. Most wrote of delight and honor to be part of the most prestigious animated films in the world. They welcomed the chance to work despite decades-long harassment from their male counterparts. Scott, Majolie, Blair and others contributed much to the beauty, whimsy, and charm audiences associate with Disney classics. Seldom credited, they were the ones who fought for the fairies who sparkle across the ice in “Fantasia,” the fluttering birds and ribbons that enchant Snow White in Disney’s first feature, and finally in 2013 saw one of their own receive full screen credit when Jennifer Less directed the wildly successful “Frozen.”

Almost from the beginning of the studio, women worked as inbetweeners, people who drew and redrew the many cells necessary to create character moves. Walt was known for his involvement in every phase of his film. According to Holt, he encouraged outstanding talent when he saw it, even when the talent came from an inbetweener — that is, a woman. Sylvia Holland was one whose talent Walt recognized immediately when he saw her sketches for “Bambi,” a film based on written treatments begun by Bianca Majoile. He promoted Holland from inbetweener to character animator, a startling move since most men served years as inbetweeners before they made it assistant animator, and then possibly to animator. Scott was the first full-fledged character animator, and it was she who created the vicious dogs that attack Bambi. She paid for this promotion by having to work as both animator and inbetweener. Majolie was one of the Disney artists who witnessed the birth of a fawn at the San Diego Zoo, capturing the moment and making it come alive in her drawings for “Bambi.” While Holland received an “Art Department” credit on the film, Majolie had none; neither did Thomas Scott, the film’s picture editor. Retta Scott, a personal favorite of Walt, was similarly not credited for her work on “Fantasia,” “Dumbo,” nor the WWII documentary “Victory Through Air Power.”

“Queens of Animation” documents everyday realities of life at the studio through Holt’s clear and intimate writing style. She weaves a multi-character chronological narrative that can be confusing if one wants to focus on a specific person. Mary Blair’s trajectory is the easiest to follow. She’s the most widely known of the women profiled, and Holt adds depth to her public reputation. She joined the studio in 1940 and almost immediately stood out for her excellent original artwork, and not incidentally, her appearance. She dressed in au courant 1950’s “New Look,” of full skirts with cinched waist, matched with three-inch high heels. When added to her natural height of 6’1”, she was an imposing figure on the lot. Blair, like several of Disney’s most talented artists, attended art schools. She was part of the “California School” of watercolor, a designation given to a group of fine artists most active from the 1920s through the 1950s. The California School was noted for bold designs and colors, which fit with Disney’s vision and immediately caught his attention. Blair worked on “Song of the South” (1948), “Cinderella” (1950), “Alice in Wonderland” (1951), “Peter Pan” (1953), and “Lady and the Tramp” (1955), among others. Her success at the studio and in a later design career belied a horrifying home life. She married Lee Blair, another artist associated with the California School, who also worked at Disney. Lee, watching his wife’s role rise beyond his at the studio, became an increasingly violent alcoholic who abused his wife and son verbally and physically, at times bashing them with furniture. Mary Blair kept this venomous home life hidden from colleagues; at work she could belong to the fantasy world of Disney.

The inclusion of Mary Blair’s hidden struggle with abuse is only one example of how Holt addresses still widespread social problems. She notes the unease of the “Darkie” stereotype Uncle Remus in “Song of the South”, and the rising racial tensions around the 1964 New York Worlds Fair where Disney premiered the “It’s a Small World” ride. Holt presents these in an unbiased way. The famous 1941 strike by Disney employees demanding that the studio accept the Screen Cartoonists Guild (later The Animation Guild, IATSE 839) is covered with similar non-judgmental writing.

Some women sided with Walt, empathetic with his control shifting to Bank of America, brought about by the huge debts he took on to keep the studio viable. Others joined the picket line, where anti-women signs and shouts greeted those still driving through the studio gates. Whatever their sympathies for the strikers, most of the single women could not afford to be out of work; none was a member of a union that might provide support. The crisis ruptured former deep friendships, often for a lifetime. The strike was settled in September 1941 when union leaders negotiated doubled salaries for full-time employees. Unfortunately for many, the agreement specified that the majority of workers, half strikers, half non-strikers, must be laid off. Women like loyal Sylvia Holland, the woman who drew the original storyboards for the film that later became “The Little Mermaid” (1989), was one of Walt’s supporters among hundreds of suddenly unemployed Hollywood animators.

“Queens of Animation” follows its key figures beyond their employment at Disney, revealing the good times and the bad in their lives. Holt is honest about their successes and their failures and is poignant in her care for their legacy. Today, the Disney Princesses are globally recognized. In 2012, Forbes reported that the authorized Disney Princess franchise grossed $3 billion worldwide; however, the magical tile murals Mary Blair created for the entrance of Disneyland’s “Tomorrowland” are no longer visible. One was chipped off in 1986, and the other, made in 1967 is probably still there, covered by plaster and images of outer space. Perhaps one day it will be restored and, as Holt does so beautifully in this book, reclaim rightful credit to the Queens who gave so much to the beloved culture of Disney.

Images of the Mary Blair Disneyland murals can be seen at https://www.yesterland.com/maryblair.html

“The Queens of Animation: The Untold Story of the Women who Transformed the World of Disney and Made Cinematic History”

By Nathalia Holt

Little, Brown and Company, 2019

379 pages

ISBN-10: 0316439150