by Rob Feld • portraits by Sarah Shatz

Brian A. Kates, ACE, counts firmly as one of New York’s quintessential indie film editors. He initially came to film through the lens of post-production, visiting his music publisher grandfather in the Brill Building as a child, and traveling the elevator with Sound One personnel transferring trim bins from editing to mixing rooms. Those rides between floors proved inspirational.

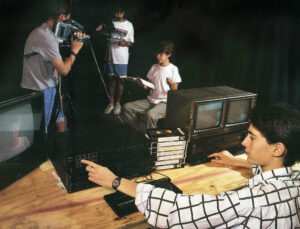

As a teenager he got an internship at Sound One, degaussing mag and watching engineers swapping reels. It was the summer of 1989; Goodfellas, Crimes and Misdemeanors, Valmont and She Devil were being mixed or edited there. “I was absolutely ga-ga, losing my mind,” recalls Kates. “I knew that was the world I wanted to be in.” Post-production is a particular environment, but the love of it remained with him through NYU Film School, where he found more inspiration from his film theory classes than his production classes.

“A lot of being an editor is loving the world of editing and finding the various stages of post-production kind of delicious in their own ways,” he explains. “Dailies are their own little beast. Then the director’s cut, which is the hardest because you have to absorb the director’s ideas about every little moment — the macro and the micro — and then manipulate them into something that makes sense. All the subsequent cuts are where the movie actually becomes good.

“The deeper thematic underpinnings of the project — which you actively try to ignore while building the movie — finally present themselves, if you’re lucky,” he continues. “And then sound, color, music and titles are the reward you get from building something that actually works. You get to be the manager of these extraordinary layers that happen at the end.”

Kates recently cut Joseph Cedar’s Oppenheimer Strategies, a US-Israel co-production, which will open in 2017. He is now winding up his second collaboration with John Cameron Mitchell as director (the first was Shortbus, 2006), adapted from the Neil Gaiman short story, How to Talk to Girls at Parties, due for release next year through A24. The sci-fi teen love story, set in 1977 Croydon, a town in south London, involves a punk rocker and a mysterious girl from…let’s just say elsewhere. It’s something of a departure for both Kates and Mitchell, but still a continuation of their interests and working relationship.

A24

“There’s a lot in Girls at Parties that might remind people of elements of John’s Hedwig and the Angry Inch [2001] and Shortbus,” says Kates. “But it’s Neil Gaiman’s source material, and the lead character Enn is really the love-child of Neil and John. I feel like we’re revisiting some of the flavor of Short because we were also reuniting our crew: producer Howard Gertler, DP Frankie DeMarco, post supervisor Matt Shapiro, sound editors Ben Cheah and Gregg Swiatlowski, re-recording mixer Lora Hirschberg, and animator John Bair.”

CineMontage interviewed Kates in Manhattan in mid-July as he was finishing the film with Mitchell.

CineMontage: What is the first thing you focus on when you’re pulling selects? Is it performance?

Brian A. Kates: Yes, but also framing, camera movement and color. I’ll use any tool I can to alter footage to make it the way I think it was intended to be. That’s a very narrow tightrope to walk because you want to make it seem as if nothing has been altered. But the way to arrive at that is to alter it in countless ways. If I see a remarkable performance where the actor breaks concentration for a few frames, and I feel like the moment needs to extend, I can just remove that look by doing a morph or a slowdown.

In the analog days, you would cut away to something and cut back, which is tricky because any cut can be a violent disruption. The trick to doing those things well is to understand the way human beings move and breathe, the way the frame rate gets interpolated as you slow down. There are some kinds of smoothing that feel human and others that don’t. Some filmmakers worry that manipulating a human face will steal some humanity. And I say, “Yes it can, but only if it’s executed badly.”

CM: Tell me about the first feature you landed, Latin Boys Go to Hell in 1997.

BK: The director, Ela Troyano, was an artist I knew while I was working on the programming committee of Mix: Lesbian and Gay Experimental Film/Video Festival. She took a chance on me. I worked the night shift on a very cheap Avid. It was a big break for me because even though the film is not very well known, it premiered in the Berlin Film Festival. And it was editorially challenging because it took its stylistic cues from Latin American telenovelas; we had to find a sincere heart in the middle of a patently over-the-top genre. And there was violence. It was the first time I had to cut a “sex-death montage.”

CM: How many of those have you cut?

BK: Crazily enough, four! Latin Boys Go to Hell, Shadowboxer [2005], Lackawanna Blues [2005] and Kill Your Darlings [2013]. By sex-death montage, I mean that if there’s an orgasm, someone’s probably also being murdered. I’ve edited that montage so many times that when I was watching Steven Spielberg’s Munich [2005], which climaxes with one, I started laughing. Michael Kahn’s beautiful work in that sequence gave me vicarious pleasure.

CM: So what have you learned about them?

BK: Each is different. Kill Your Darlings takes that sensationalistic premise and does it simply and poetically. The character, David [Michael C. Hall], is imploring Lucian Carr [Dane DeHaan] to kill him as an act of mercy for unrequited love, we learn later. That scene is intercut with Allen Ginsberg’s [Daniel Radcliffe] deflowering, as it were, and also with William Burroughs’s first experience shooting heroin. So there’s something tragic about the sequence, but it’s also exuberant and kind of sacred — with a feeling that all of these events are somehow pre-ordained. Nico Muhly’s score for the sequence is a big part of that, and obviously the way director John Krokidas got Dan Radcliffe to understand how to hit his…emotional beats.

Latin Boys, on the other hand, is pulpier and over-the-top. In fact, a piñata explodes at…you can probably guess which point. Shortbus has a sex montage without any death — it’s not a violent film — but it does have a piñata! Everything old is new again.

CM: How to Talk to Girls at Parties is actually your third collaboration with John Cameron Mitchell; you edited Shortbus and he executive produced Tarnation [2003]. How has your process with him developed?

BK: In terms of workflow, there were many aspects common to both films: John doesn’t watch dailies while shooting unless the scene is incomplete and he needs to match something later. Not watching keeps him focused on the actors, optimistic and forward-thinking, and it gives me almost complete freedom in the editing room during the shoot.

When we begin cutting together, he spends every morning for a month or so watching everything he shot, and writing detailed, time-coded e-mails with all of his selects. My assistant, Chris Rand, strings out John’s selects and I compare them to my assembly, and then recut. Sometimes there’s a lot of overlap between those two versions and sometimes the second cut goes in an entirely new direction. In the afternoon, we work together. It’s a system I love — the director gets to know the footage intimately and is monitoring what goes in, yet it’s up to me to work out the puzzle of the construction. Then we synthesize all that together in the room.

CM: And that was pretty similar to Shortbus?

BK: John’s voice is amazingly consistent in both films, in my opinion. There’s a wry sense of humor, a love of wordplay, a mixture of slapstick gags and erudite references to philosophy, history and politics — sometimes all in a single moment. And there’s a deep sense of melancholy. Shortbus is known as a comedy with non-simulated sex, but it’s really a cathartic ode to broken young people trying to find connection. It’s a 9/11 movie; it literally begins over the open wound of Ground Zero and is about damaged people trying to fill each other with something meaningful. Now, that could sound pretentious since it’s a movie about literally getting filled, getting permeated — sex — but that connotation is working on a subliminal level.

“Great directors encourage me to be bolder in my choices.”

– Brian A. Kates

With How to Talk to Girls at Parties, superficially we have a 1977 teen romantic comedy. But if you see it from all angles, it’s an ecological parable, a treatise on punk and the limits of anarchy, the invention of a new cosmology, a reinterpretation of ’70s sci-fi — which was already a bit post-gender — seen through a 2016 post-gender lens. Heady stuff. But it’s all done with a spirit of youth, fun, music and color. It’s that combination of lofty philosophy with the silliest, most unpretentious, unfiltered stuff that I absolutely love. And I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention that John had final cut on both films, which is a testament to great producing.

CM: You’ve managed to work on a great deal of queer cinema. How does that identity and voice come into play in your work?

BK: I’d say it’s about embracing a point-of-view from the margins, and that goes for the queer stuff as well as the African-American history-related films too: Lackawanna Blues, Bessie [2015], Lee Daniels’ The Butler [2013] and Oscar’s Comeback — an upcoming doc about the legacy of director Oscar Micheaux. And it’s in Oppenheimer Strategies, in which Richard Gere plays a classic outsider role: a modern interpretation of the “Court Jew,” a mid-level businessman being manipulated by political powers beyond his control. I think I initially realized I was attracted to that kind of oblique perspective when I saw Robert Altman’s Three Women [1977] when I was a teenager. It was on WTBS constantly, probably because it was one of the cheapest films the network could afford to play. I knew Altman because I loved Nashville [1975], but Three Women had no mystique or reputation that I was aware of. But I was so into it, and later found that other gay friends of mine had been into it as kids, like Jonathan Caouette, the director of Tarnation.

It’s a film that revels in Americana — but a fading, creepy, consumerist Americana — where the vastness of the desert landscape competes for attention with Millie Lamoreaux’s (Shelley Duvall) recipes for tuna melts. There’s a friendship between two young women in Southern California who are sort of social embarrassments to those around them, though the film doesn’t mock them. The third woman is a painter who enters their circle, injecting their dynamic with a kind of pagan spirituality that is arresting, and they all end up living in a kind of quasi-feminist enclave. It was queer in a way that wasn’t about homosexuality but about aesthetic boldness and non-narrative techniques.

For instance, the ending is a total non sequitur. When I was in high school, I discovered a copy of Ephraim Katz’s The Film Encyclopedia [1979] in the school library and was floored that under the entry “Ambiguity,” he cited the ending of Three Women. It validated the intentionality behind that kind of anti-narrative, a method to the madness. There was no Queer New Wave for me to attach myself to — I wasn’t in that world yet — but the idea of exploding narrative into more experimental forms was kind of a version of queerness that I started to love.

CM: It sounds like you don’t feel pigeonholed by the work you’ve done.

BK: I don’t, because the identity stuff is a prism to understanding all different kinds of storytelling. The brilliant Andrew Dominik hired me to edit Killing Them Softly [2012], a violent crime drama starring Brad Pitt, because he saw the no-budget queer documentary Tarnation on my resume and wanted to meet me. Tarnation depicts a co-dependent relationship between a queer kid in Texas and his ill mother, while Killing Them Softly takes on another “outsider” world of contract killers and gambling rackets. I take little credit for Tarnation because a lot of it was constructed before I came on; I acted as a kind of dramaturge with producers Stephen Winter and John Cameron Mitchell. But it’s a great film and takes many experimental risks to which Andrew was drawn.So, in a way, that’s the opposite of being pigeonholed.

CM: What kind of projects tend to attract you?

BK: I gravitate to films that are exciting on more levels than one, and I think it’s opened up doors for me because great filmmakers respect that. I want to have more of that in my career. Great directors encourage me to be bolder in my choices. After many years of editing, I’m still afraid of letting shots play long and have rhythms that are disturbing because they make the audience uncomfortable. I want to work with collaborators who say, “No, I know you’re excited by these impulses, and I don’t care what the distributor says; we’re holding on that shot and let’s do it together.” That’s a perfect collaboration to me.