by Edward Landler

In 1225, Robert Hode fled the jurisdiction of the king’s court in Yorkshire and on public record was declared “outside the law.” Over the century before Hode appeared on public record and over the three centuries following, numerous stories developed by word of mouth in the shires of Nottingham and York. These tales recounted the exploits of the various outlaws sheltered in Sherwood Forest, which lay between the two shires.

As these local oral traditions came to be written down, the various outlaws became perceived as one band of outlaws led by Robin Hood. Since the 1500s, these stories spread throughout the world, eventually becoming familiar to audiences through the medium of cinema.

The Little Johns, Will Scarletts and Friar Tucks of movies today would still be recognizable to the tales’ original audiences. In the earliest lore, they killed the king’s deer and robbed the wealthy and the corrupt clergy. A few sheriffs including the Sheriff of Nottingham pursued them, yet Robin and his band swore allegiance to the king. The king was never identified as Richard I until the late 1500s.

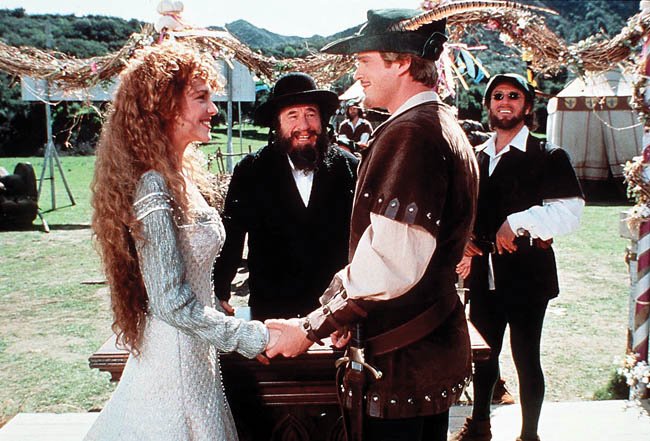

Around the same time, a popular May Day ritual combined two folk traditions by dramatizing a wedding of Robin Hood to the Queen of the May. Soon, stories emerged linking Robin with a May Queen who was now a noble, Maid Marian. Robin then became the Earl of Huntington, whose lands had been confiscated by the crown. In the original lore, Robin was a yeoman—a freeman but not a noble. Guy of Gisbourne, a bounty hunter after Robin’s head, and also a yeoman in the original stories, became a noble in 17th-century versions. Alan-a-Dale, the minstrel, was introduced to the legend around the same time.

Until the 1800s, the Robin Hood tales had not suggested any enmity between Normans and Saxons. Richard I, in whose reign Robin’s activities were now firmly set, lived over a hundred years after the Norman Conquest of Saxon England. By then, Norman-Saxon hostilities had been put aside. But Sir Walter Scott’s 1820 novel Ivanhoe established the perception that the Normans continued oppressing Saxons into Richard’s reign. By making Robin Hood a character in his novel, Scott embedded this in the legend, along with the true story of the ransom demanded to free Richard from captivity in Austria.

The 1800s also saw the growth of Robin’s role as a champion of social justice. While a few of the original tales depicted him helping peasants, they did not call for changes in the social order; they simply recognized the realities of wealth and power. As the divine right of kings waned and equal rights arose, the legend assimilated the call for social justice. The theme of stealing from the rich specifically to give to the poor became more prominent in the tales, and Robin Hood became a liberator of the oppressed.

By the time movies arrived, all the elements of the legend were in place—except for a cohesive plot line. Books about Robin Hood only tied the various tales and anecdotes together as a loose string of episodes, and the earliest short silent films simply presented tableaux of pageantry recreating separate adventures.

The major silent Robin Hood carried on the pageantry but far more spectacularly. Written by its star, Douglas Fairbanks, under the name of Elton Thomas, this 1922 film kept little of the oral tradition. Returning from the crusade, Fairbanks’ Earl of Huntington assumes the name Robin Hood to protect England from Prince John’s cruelties.

Heightening the pageantry, director Allan Dwan draws from traditional May Day imagery in the tournament where Robin and Sir Guy vie for Maid Marian’s hand. Also evoking May Day, the outlaws ambush the Sheriff’s men in the forest, ending with a rhythmic montage of Will Scarlett twirling one soldier over his head and throwing him to Friar Tuck who then throws him to Little John who tosses him onto a tree limb.

Unlike Fairbanks, the writers of the 1938 sound The Adventures of Robin Hood—Seton I. Miller and Norman Reilly Raine—entwined the traditional tales with the 19th-century historic context. This movie, with Robin Hood in the person of Errol Flynn, defined the legend as the world knows it today and set the standard by which all later versions would be judged. It also won Ralph Dawson an Oscar for Best Editing.

In the original lore, the stories stand by themselves: Driving off the Sheriff’s men after killing the royal deer, Robin’s first meetings with Little John and Friar Tuck, his rescue from the gallows, the disguised King’s journey through Sherwood—these were all related as separate incidents. But in The Adventures, directors Michael Curtiz and William Keighley linked these episodes to tell the story of Sir Robin defending England against Norman injustices in the name of the rightful king.

Still affected by the Great Depression, audiences of 1938 could identify with Flynn’s Robin Hood. His righteous struggle bolstered the hopes for economic justice offered by democracies in contrast to the order imposed by Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia. Technicolor and Ralph Dawson’s editing reinforced the impact of these themes.

Dawson constructs action scenes with an economy and rhythm that keep viewers aware of the geography of the entire action. For example, the editing of the outlaws preparing the ambush on the royal caravan is echoed in the raid itself. The audience is always clear about where and when each action is taking place. The shifting spatial relationships between the major characters drive the logic of the editing but also allow for engaging vignettes––like the ground-level shot of a row of green-clad outlaws leaping over the camera cutting to a higher shot of the outlaws from the side as they jump onto the soldiers’ horses.

Even cartoon characters including Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck and Popeye the Sailor have taken on the guise of Robin Hood. A 1973 Disney musical animated feature, Robin Hood, cast all the characters as animals—Robin and Marian foxes, King Richard and Prince John lions, Little John a bear. British actors voiced the “noble” characters while the commoners had voices of actors known for their roles in Westerns.

The first major British Robin Hood movie was produced by Walt Disney in 1952—The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men. Filmed in Sherwood Forest itself, the authentic castles are sized more appropriately to human dimensions than the grandiose sets of Hollywood. Clothes look worn and lived in and the villages are realistically rustic.

Director Ken Annakin depicts a more realistic social setting by incorporating traditional folk customs into the action. As punishment, the Sheriff’s men wrap a poacher in deer skin, tie antlers to his head, and beat him in the Nottingham village square. Villagers raise cries of protest against the Sheriff and join to help Robin rescue the poacher.

The Story of Robin Hood also introduces a more assertive Maid Marian, who disguises herself as a boy to join Robin’s band. Marian’s empowerment becomes more

pronounced in the long-running British TV series of the late 1950s entitled The Adventures of Robin Hood and starring Richard Greene. In this version, she often wears men’s clothing and matches arms and wits with both Robin and the Sheriff. This series also consistently focuses on themes of social justice, some of its scripts furnished by American writers blacklisted during the McCarthy Era.

Two later British TV series, Robin of Sherwood (in the 1980s) and Robin Hood (recently ending a four-year run) presented even stronger, more contemporary Marians and introduced Muslim characters into Robin’s band. Deviating from the realism of the original tales, Robin of Sherwood made sorcery central to its storyline while the 21st-century Robin Hood focused more on personal rivalries than on social justice.

Another British TV series, Maid Marian and Her Merry Men––a children’s comedy of the early 1990s––best reflects how contemporary social attitudes have influenced the legend. Here Kate Lonergan’s Marian revolts against the status quo while Robin is a tailor who joins the outlaws to design their outfits. Barrington, a dreadlocked black Rastafarian, introduces every show with a hip-hop song.

Mel Brooks transforms Barrington into a quartet of black rappers to introduce his Robin Hood: Men in Tights of 1993. But Brooks is more concerned with sending up pop culture icons than with social satire. The main target of mockery is the 1991 Kevin Costner movie Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, directed by Kevin Reynolds. Dave Chapelle’s Moor and Tracey Ullman’s witch are obvious take-offs on both Morgan Freeman’s character and the witch character from the Costner movie—both of whom had likely been adapted from the Robin of Sherwood TV series.

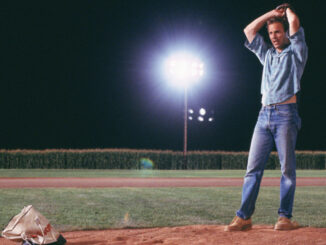

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves was the last major production based on the legend until Ridley Scott’s upcoming release. It departs almost completely from the original tales and, after Robin’s escape from Jerusalem, removes the story from history entirely. Alan Rickman’s Sheriff of Nottingham—instead of Prince John—tries to usurp the throne here, by forcing his marriage to Maid Marian, who is of royal blood.

Of the movies and TV shows since the 1950s, two stand on their own as imaginatively well-grounded treatments of the legend. In fact, Robin and Marian, directed by Richard Lester in 1976, is substantially a logical sequel to the 1938 movie. Embracing the traditional tale of Robin’s death, writer James Goldman transforms it into the story of Robin’s return to Nottingham after 20 years of warring in France with King Richard.

A tale of aging and disillusionment, Sean Connery’s Robin returns home to discover the Sheriff still in power in Nottingham and Audrey Hepburn as Marian now the Abbess of Kirkslee Priory. When Robin leads the peasants once more against the Sheriff’s harsh rule, he finds a disparity between his ideals and his age.

John Victor Smith’s editing conveys these themes through sequences set in the outlaws’ old camp. After the first night reunited with his band in Sherwood, Robin and the others rise one by one in the chilly morning with aches and pains, as they adjust their well-worn clothes and wash in the stream.

The settings are authentic, as in the 1952 Story of Robin Hood, and keen attention is paid to daily living realities, frequently showing peasants working in fields and orchards along the roads between villages and castles. Particularly in contrast to the other movies, we see that wielding broadswords and scaling castle walls entail draining physical exertion.

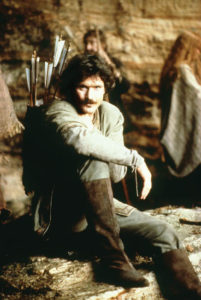

The other imaginative post-’50s treatment is Robin Hood, starring Patrick Bergin, directed by John Irvin, written by Sam Resnick and John McGrath, and released in 1991 as a US TV movie in the shadow of the Costner version. Leading Robin Hood scholar J. C. Holt served as advisor and, although the writers made the hero the Saxon Earl of Huntington, they also gave him the pre-outlaw name of Robert Hode.

Uma Thurman’s Marian has the strongest character of all her counterparts. The story follows the growing maturity of this spoiled Norman noblewoman as she recognizes the injustices of the feudal system. Seeking understanding and attracted to Robin’s resolute daring, she disguises herself as a boy to join his band. Her skill at arms and her growing resolve help bring Norman and Saxon together in peace.

An Army of Archers

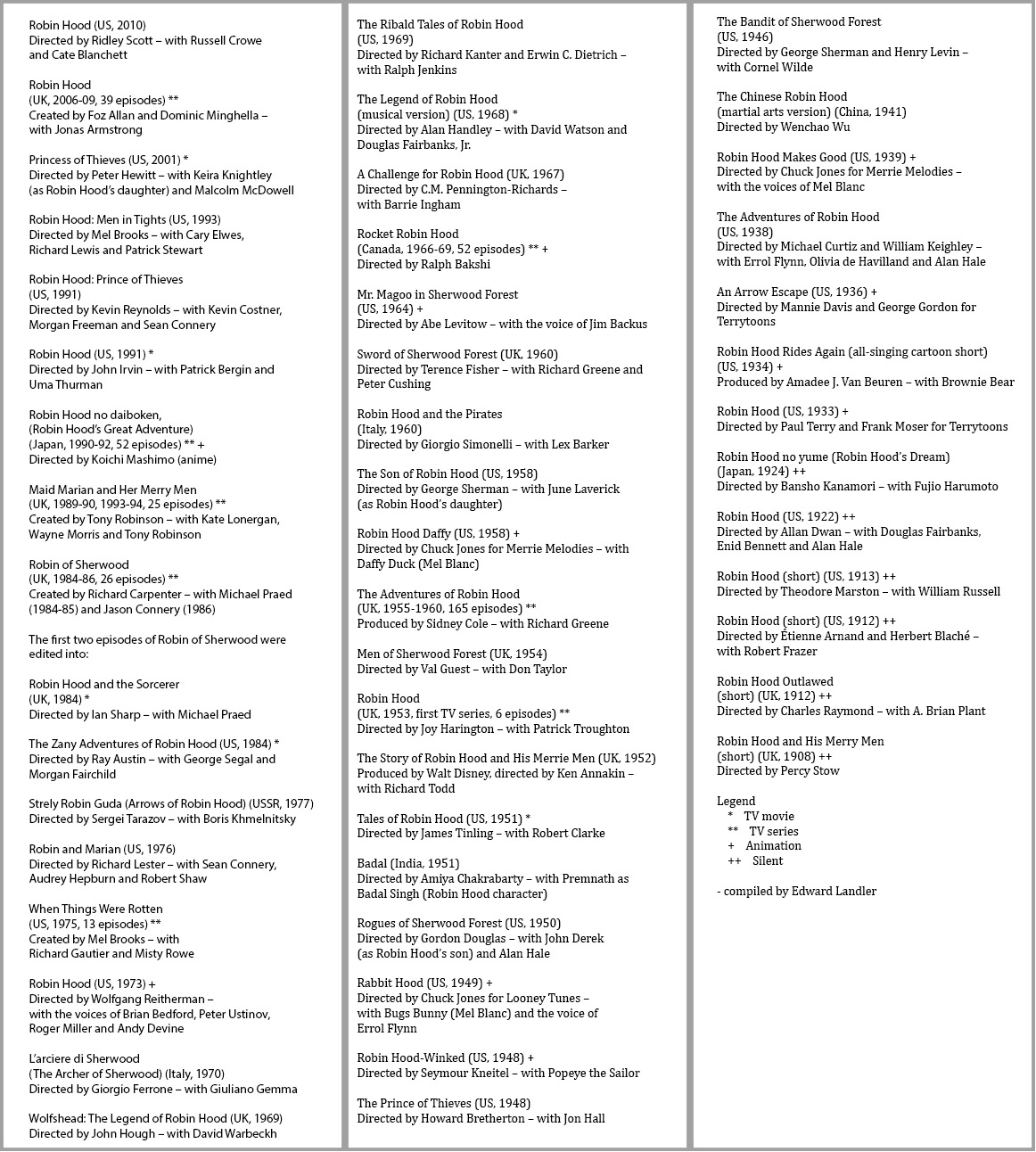

A Selected Hood-ology

The cinematography of the natural locales suggests a sense of the characters’ deep relationship to their environment. The opening sequence draws viewers directly into the life of Sherwood, interweaving close documentary shots of wild forest creatures—rabbit, fox, badger, deer—with details of servants’ preparations for the nobles’ hunt. This leads seamlessly into the story’s beginning, in which Robert Hode defends a hungry poacher against the Norman nobles.

This sequence displays the intricacy of Peter Tanner’s editing, which also observes the vital differences between rich and poor that the legend has come to embody. The longevity of the Robin Hood story and its lasting appeal has much to do with these ever-present realities of haves and have-nots and the innate human desire to be treated fairly.