By Joseph “Jay” Duerr

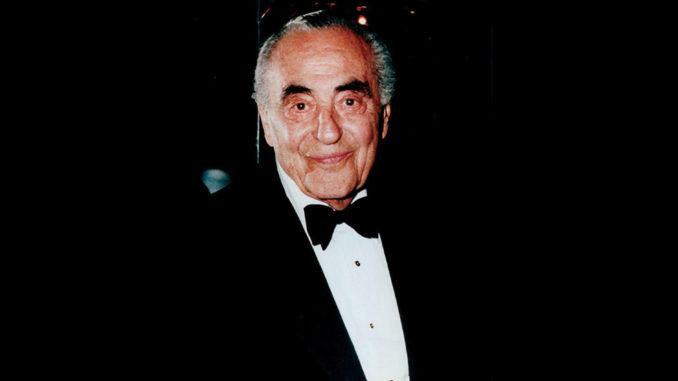

The Editors Guild lost its oldest active member granted a 50-year honorary status, Ralph E. Winters, of natural causes on February 26th in Los Angeles. Winters, age 94, had been a member of the Guild since mid-1937.

Winters was a two-time Academy Award-winning film editor, whose 70-year career spanned nearly the entire era of talking motion pictures. He actually broke into the motion picture business in 1928. He was nominated for an Academy Award for best film editor six times. He won for 1950’s King Solomon’s Mines and 1959’s Ben-Hur, which is still famous for its stunning chariot race scene. His other Oscar nominations were for Kotch (1971), The Great Race (1965), Seven Brides for Seven Brothers(1954) and Quo Vadis? (1951). In all, Winters worked on more than 70 films, including On the Town, Butterfield 8, Gaslight, The Hawaiians, The Thomas Crown Affair, How to Succeed in Business without Really Trying, the 1974 version of The Front Page and the 1976 version of King Kong.

He teamed with acclaimed writer-director Blake Edwards close to a dozen times, editing such Edwards’ classics as The Pink Panther, 10, Victor/Victoria and S.O.B. Frank J. Urisote, a Guild member who had known Winters since 1957 at MGM, told CineMontage shortly after learning of Winters’ passing: “Ralph taught

me how to conduct myself in the business. He used to tell me, ‘It’s really nice to be

important, but it is more important to be nice.’ ”

Winters is survived by his wife, Lulu, and five daughters. His first wife, Teddy, died in 1985, after more than 40 years of marriage.

The last film Winters worked on was Cutthroat Island in 1995. It was during

that same year that the Winters feature article below appeared in the Editors Guild

newsletter. We are reprinting this piece for our members to appreciate since Ralph Winters offers some treasured advice that still holds true today. We hope you enjoy this final moment with Ralph E. Winters. – Sharon Benoit

A Good Cut

“Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” – George Santayana

An Interview with Ralph Winters

Ralph Winters was born in Toronto in 1909. He started at MGM In 1928, where his father worked as a tailor. When asked to pick his four most significant credits, he chose to pass by two of his more famous ones, Ben Hur and The Pink Panther, and instead chose to list Gaslight, for its delicacy of dialogue cutting; King Solomon’s Mines, which was “made from spit and baling wire;” High Society, from which he learned not to argue with directors; and The Great Race, on which he just had lots of fun. Looking back at his 75 credits and two Academy Awards, Ralph said that he has made his share of errors but has no regrets. Ralph was president of the Motion Picture Editors Guild from 1965 to 1966, and served on the Board of Directors for many years.

Ralph Winters isn’t as old as Santayana but he did begin his career way back, and he’s still editing today. We, as a Guild, have much to learn from him and our other senior members. From the chariot race in Ben Hur to the presidency of our union, Ralph’s history reflects our collective past. We spoke with him about what it was like before the union came into being, about promises made and broken, lack of overtime pay and threats if you complained. But also about the joy of editing, the respect that editors command today, and the struggle to do good work in often-difficult circumstances.

Ralph began his career at MGM, coming up through the ranks and learning his craft assisting older, more experienced editors. After sound came in, silent versions of the films were made for the theaters that were not yet equipped with sound. Ralph edited many of those silent versions, cutting in title cards and learning all the time.

While working as an editor, Ralph found the time to actively support the union. He was on our Board of Directors for 20 years.

He saw us struggle and grow, and then watched as a large pool of non-union labor started to form in the 70’s and 80’s. Many of these people were kept out by union restrictions. This, he believed, was a big mistake, and he happily watched as those restrictions ended. When a group of young assistants circulated a petition to allow members to become editors after five, rather than eight years, Ralph seconded the motion at a General Membership Meeting to applause from some young enough to be his grand- children.

Ralph believed one of the most insidious changes is the greed that pervades the huge conglomerates that now own the studios.

Ralph believes it is vital for editors to support and help their assistants. He has watched the salaries of picture editors, now represented by powerful agents, rise to unimagined heights, yet sees that many will not raise their voices to get their first assistant a few more dollars a week. He told how Blake Edwards, for whom Ralph cut many films, went to bat for him at Warner Bros. when he wanted an extra $50 a week.

This was the era before agents represented editors. Edwards encouraged him to stand up to the producer.

“When somebody wants you,” Ralph says, “that’s the only club you have. Whatever these guys are making today, they still have to have a club. They have to have a director that wants them and is willing to got to bat for them. And many directors and producers do go to bat for their editors. Whereas the editor often does not go to bat for his assistant. And I think that’s wrong. Of course, the assistant must speak up and let the editor know what his needs are. He must stand up for himself.”

Ralph sees the changes in our industry producing both positive and negative results in the search for excellence that we all strive for. “I think the young directors and producers have come along so fast that they accept less than the best in editing. Because they don’t know the best. Because of their lack of knowledge. Of course, these schedules today are shocking. It’s hard to do good work.” He adds, however, “Sometimes if a bad cut gets 50 feet of bad film out, then it’s not a bad cut. It’s a good cut.”

Ralph believes one of the most insidious changes is the greed that pervades the huge conglomerates that now own the studios. Though the movie industry has always been a business, Ralph points out that “in the old days, your Mayers and your Laemmles and the old time directors grew up with the film. And they loved film. Today they love money.”

From the chariot race in Ben Hur to the presidency of our union, Ralph’s history reflects our collective past.

In spite of this, he thinks it’s still a great time to be an editor. We have a lot more standing today than ever before. With more money comes more respect and recognition of how important editing is. With the possibility of endless manipulation of images during postproduction, the importance of the editor increases tremendously. “We as a group,” says Ralph, “have to help to make every picture ever made as good as it possibly can be. When you go in to work on a movie that’s what your thinking should be. You’ve got to work on every film as if it’s the greatest thing you’ve ever worked on in your life.”

Ralph Winters and all our members are ready to apply 75 years of storytelling through editing to any film, television show, CD-ROM, or any other medium that comes along.

1995 Contributors to this article were Bruce Green, Jeff Burman and Rachel Igel.

Guild Members will remember Ralph Winters as an individual who loved the art of film editing as much as life itself. His advise and contributions to the motion picture industry will most certainly be missed. – Sharon Benoit