by Bill Desowitz

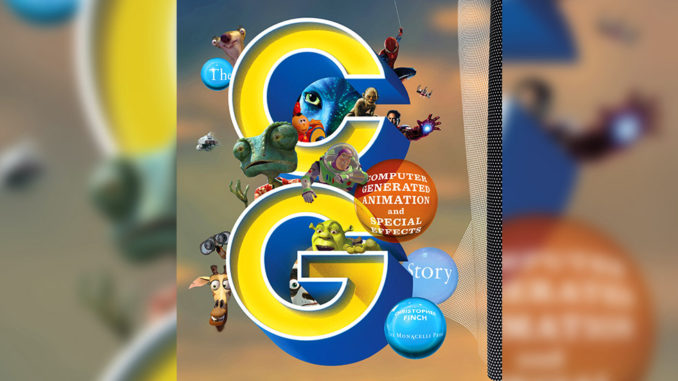

In light of the multiple-Academy Award-nominated Gravity’s brilliant success as a computer-generated hybrid — everything in space was animated as a process of reverse engineering, with the exception of the faces of stars Sandra Bullock and George Clooney — the timing couldn’t be better for The CG Story. It’s a lavish and informative coffee-table book about the evolution of digital visual effects and computer animation, as well as their inevitable convergence. From Star Wars (1977) through Life of Pi (2012), and from Toy Story (1995) through Wreck-It Ralph (2012), author Christopher Finch covers personal vision, technological innovation, directorial imprint and individual challenges. And he does so by alternating back and forth between effects and animation.

Today, of course, CG is an integral part of visual storytelling; last year’s box office leaders were once again dominated by animation and visual effects. And the cinematic experience has become more believable and immersive. But to understand this convergence, in which animation has become more like live action — and vice-versa — Finch takes us back to the pioneering work of Douglas Trumbull (2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968; Close Encounters of the Third Kind, 1977), Pixar/Disney’s Ed Catmull (Toy Story) and John Dykstra (Star Wars), among others. As a result of early breakthroughs in motion-control photography (which became programmable and digitized with Star Wars), front projection/compositing (on Close Encounters) and CG animation/rendering (in academia, especially), the groundwork was laid for the photorealism or hyper-realism we now enjoy in live action and animation.

In his prologue, Finch recalls how actor Victor Mature once declared that his ambition was to star in a movie without actually appearing in it, and in an interview with Robert Zemeckis (The Polar Express, 2004), the director told me that his dream was to make a movie entirely in the computer. This has become a reality with CG.

But the CG revolution in visual effects took hold before the one in animated films because the studios demanded more sophisticated imagery while the dominance of hand-drawn animation persisted at Disney. In the meantime, Catmull and John Lasseter helped George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic become an industry powerhouse: Labyrinth (1986) contained a naturalistic CG rendering of an owl, Star Trek IV: The Long Voyage Home (1986) offered 3D morphing, The Abyss (1989) boasted fluid dynamics for the liquid alien, and Total Recall(1990) introduced motion-capture. Motion-capture sped up the animation process — particularly for humans — and has now become a staple of the industry, thanks to Andy Serkis’ Gollum (The Lord of the Rings, 2001-03; The Hobbit, 2012) and Caesar (the latest Planet of the Apes reboot, 2011), Tom Hanks’ multiple characters (The Polar Express) and Bill Nighy’s Davy Jones (Pirates of the Caribbean films, 2006-07).

With Avatar, Cameron and Weta Digital took us to an alien world that was fully animated and, at the same time, spearheaded by the return of 3D. This necessitated the creation of a new pipeline and a workflow that made animation work more like live action.

Linear connections abound in The CG Story. Thus, it’s no coincidence that there was a ripple effect throughout the industry after ILM’s CG-animated breakthrough with dinosaurs in Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster Jurassic Park (1993). This led to Pixar’s triumphant Toy Story as the first CG-animated feature two years later, and Disney, which released the film, felt that the commercial potential of computer animation was too lucrative to keep under wraps. At the same time, the studios intensified the making of thrill-ride action/adventures, demanding that the bar constantly be raised for better and better visual effects.

Speaking of animation, early on in the book, Finch spends a great deal of emphasis on the development of Pixar, DreamWorks, Pacific Data Images (which was bought by DreamWorks and contributed to the success of the Shrek franchise, 2002-13) and Blue Sky (Ice Age, 2002). Then, on the effects side, the author discusses the continuing pre-eminence of ILM as well as the rise of Digital Domain (Titanic, 1997; The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, 2008), Sony Pictures Imageworks (the Spider-Man franchise, 2002-12), Peter Jackson’s Weta Digital, Rhythm & Hues (The Chronicles of Narnia films, 2005-10) and others. He later points out the global contributions of the visual effects industry, as London’s Soho district (including Framestore, Double Negative, Moving Picture Company) became a major player with the popularity of the Harry Potter franchise (2001-11).

Likewise, the 21st century continues the era of the superhero (from Christopher Nolan’s gritty Batman to Marvel’s gallery of social misfits, including Iron Man) demanding greater emphasis on performance and more naturalistic visual effects. But the complexity of the work and the pressure from the studios to make it quicker and cheaper has led to increased globalization and sharing of assets, which Finch unfortunately fails to address because he can’t see the proverbial forest through the trees. He gets bogged down by technology in the second half of the book, and tries to cram in as many movies as possible so it remains timely and relevant.

But Finch does an excellent job of discussing the game-changing perspectives of Andy and Lana Wachowski (The Matrix trilogy, 1999) and James Cameron (Avatar, 2009). These directors impacted the industry with a new kind of immersive, mind-bending storytelling that relied on the development of groundbreaking technology to convey alternate realities. In the case of The Matrix movies, the most famous example is “Bullet Time,” developed by visual effects designer John Gaeta and inspired by the earlier “bullet dodging” Smirnoff commercial and the animated cyberpunk classic Akira (1988), which combines conventional photography (though using a virtual camera) with CG effects to alter time and space.

The cinematic experience has become more believable and immersive. But to understand this convergence, in which animation has become more like live action — and vice-versa — Finch takes us back to the pioneering work of Douglas Trumbull , Pixar/Disney’s Ed Catmull and John Dykstra , among others.

With Avatar, Cameron and Weta Digital took us to an alien world that was fully animated and, at the same time, spearheaded by the return of 3D. This necessitated the creation of a new pipeline and a workflow that made animation work more like live action with the help of onset virtual-capture in real time. This special hybrid refined everything previously achieved in animation and visual effects. Avatar, therefore, was the new poster child for virtual production after becoming king of the box office. It’s a paradigm shift that’s nonlinear with more front-end collaboration, including editorial, which Gravity proved, as editor Mark Sanger worked closely with director/editor Alfonso Cuaron in cutting the space thriller essentially like an animated movie, beginning with complete, pre-lit pre-visualization.

What’s fascinating about The CG Story, therefore, is the realization that live action has become more like animation and vice-versa, thanks to the advances in technology and artistry. And with the advent of the virtual camera and the digital backlot, everything has convincingly become CG. It’s been suggested that Gravity could even qualify as an animated feature. Then we’d really have come full circle.