By Joseph “Jay” Duerr

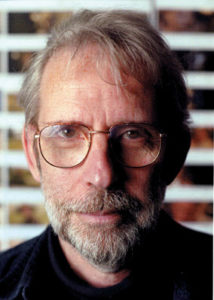

“There’s no question that film – any film – is a kind of visual music: the alternation and development of individual shots being the equivalent of the alternations and development of phrases in music.” – Walter Murch, Apple Pro Film

Walter Murch’s fluid editing style always sweetens the soundtrack of every film he’s cut. Whether it be an award-winning score composed by Gabriel Yared for The English Patient or featured compositions by Czech composer Leos Janacek in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, music sticks like glue to the sequences of his images. From a music editor’s perspective, I thought it was time to have my “conversations” with Walter Murch about the marriage of film and sound.

So, I caught up with him at the Berlin Film Festival in February where he was lecturing 500 selected young filmmakers from around the world. He had just finished a 16-month stint carving over 112 miles of footage and extracting that elusive thread that binds the final cut of Cold Mountain. Speaking slowly and evenly with his Walter Cronkite-like baritone, Murch grasps for that perfect analogy in explaining the connectivity that his film work has to the other artistic and scientific endeavors.

Joseph “Jay” Duerr: Why this comparison of film editing to music composition?

Walter Murch: When the time comes to place a piece of music that feels right for a scene, you discover that, with a little shuffling, it’s almost guaranteed to have this fantastic and synchronous relationship with the image for about a minute or two without any editorial interference. It’s as if the composer and the performers were looking at the image when they recorded the music. How can things line up? How can the key change happen at just the right moment when the scene changes its internal emphasis? Sometimes the colorations will seem to alternate back and forth almost with the cuts, even though when you assemble the scene to picture your only thoughts of reference were internal to the scene. There has to be some kind of mysterious crystallization that is guiding the assembly of images in the same way that a composer deals with the establishment of certain rhythms and musical phrases.

JJD: Is there an intuitive rhythm to the way you cut?

WM: Certainly. One of the jobs of an editor is to sensitize oneself to the deep rhythms of the work itself; how the actors perform their scenes; how the director and the actors have come up with rhythms and how those rhythms get picked up by the camera operator. It’s your job as an editor to soak up those rhythms and extend what you’ve learned into areas that are not inherently rhythmic.

For example in Riply, there is a shot of Matt Damon shivering on the shore after he has killed the Jude Law character. The next shot is his POV of the empty ocean. How long do you hold that shot? There is no motion or action that cues you. But by that time in the film you have gotten an internal metronome ticking out that tempo of thoughts that the character is thinking and the thoughts that you want the audience to think about those thoughts. And when those thoughts have reached a certain ripeness or certain point is when you make that cut.

JJD: Is this one of the reasons why you like to cut without sound? Some editors feel that using a temp music track helps them with certain scenes. Have you ever done this in the past?

WM: No. Cutting to a music track usually confuses the issue. I try to make the scene work on its own visual terms and dramatic structure in a way that is “ musical.” Paradoxically, the longer I stay away from inserting music on a scene the better music fits.

JJD: You mentioned that the first assembly of Cold Mountain was six hours long.

Can you explain the process of moving from a first assembly towards the final cut?

WM: When Cezanne was doing a portrait, he kept asking the person to come back. After the 25th sitting, he finally told that person that it wasn’t going to work out. “Just go away and let me work on the picture myself.” He then stood in front of the canvas and said, “Gee, it doesn’t seem to be working, but is there anything in here that works?” Then he looked further into the painting and realized, “You know, I like the area where the color goes around his neck. Something about that that I like!” Well then, without any reference to the person whose portrait it is, he extended that “into the rest of the picture.”

It’s like finding a little place where the crystal that you are trying to form is right and try to extend that crystallization into every other area as far as you can.

JJD: Can you cite examples of those crystallizations that you found in the first assembly of Cold Mountain?

WM: (Laughs) I knew that question was coming. It’s ironic and not usual that they

were found in areas that have now been subsequently cut out of the film. There was a scene with Sarah (Natalie Portman) after the third soldier had been killed. Contrary to the novel, the script went on. The baby got sick and died, then Sarah committed suicide. During this sequence, Inman was helping her by slaughtering and salting her pig for the winter months. Every time that scene would go by Anthony would comment, “If we could only make the rest of the film like ‘that.’ That sequence felt like you were really there.” The scene stayed in the film up to a couple of months before the final cut. It obviously didn’t get cut for the verisimilitude that was on the screen, but because the emotional weight – the baby’s death and mother’s suicide – was too much for the film to hold in that point of the story. The weight of these images was too much.

JJD: In both the reactor repair sequence in K-19: The Widow Maker and at the end of the battle of Petersburg in Cold Mountain, you seemed to counterbalance the weight of those images with the sound.

WM: Absolutely. I call this clear density/dense clarity. The image of clear density is a piece of quartz, which is heavy in the hand but beautifully clear

to the eye. For instance, in the battle of Petersburg, the chorale music used clarified and rendered more transparent the “dense” images of that sequence. On the other hand, you might want to add density to an image. One example is the scene in the Godfather before Michael (Al Pacino) kills Sollozzo.

This was just a dialogue scene in a restaurant. One third of the dialogue was in Italian without subtitles so the audience was really thrown back on the images of just the faces. Francis (Ford Copolla) didn’t want music under the scene, reserving the big tutti chords after the murders and after Michael had dropped the gun. So hence, the rumbling screeching train noise came in before the act of murder to densify a scene that was very clear in what was going on.

JJD: Is it true that you also prefer using sound as the bridging element between scenes and time transitions? You rarely use picture dissolves. Why the choice?

WM: I would never make a dissolve that isn’t graphically interesting simply to say “and time passed.” If two images actually go together in an interesting way visually and get across the idea of time transition or the metaphysical collision between the ideas, then I’m perfectly open to it. By usually pre-lapping the sound, you can do much the same whereby colliding the images may overstate the case. With sound you are much more flexible with what you can overlap. With the image you are stuck with what you have.

JJD: Your decision to cut Cold Mountain using Final Cut Pro was a bold step, but no surprise to many since you have thrust yourself onto the “bleeding edge” of technology many times before. Do you find that the process of learning new technologies may precipitate those “serendipitous” events that may otherwise be left undiscovered?

WM: So, by purposely breaking familiar and comfortable work habits, it makes you examine the process more closely. It also throws up some random elements that would otherwise be too comfortable. I am open to that. Believe me, I understand people who are not open to it. It’s a question of temperament.