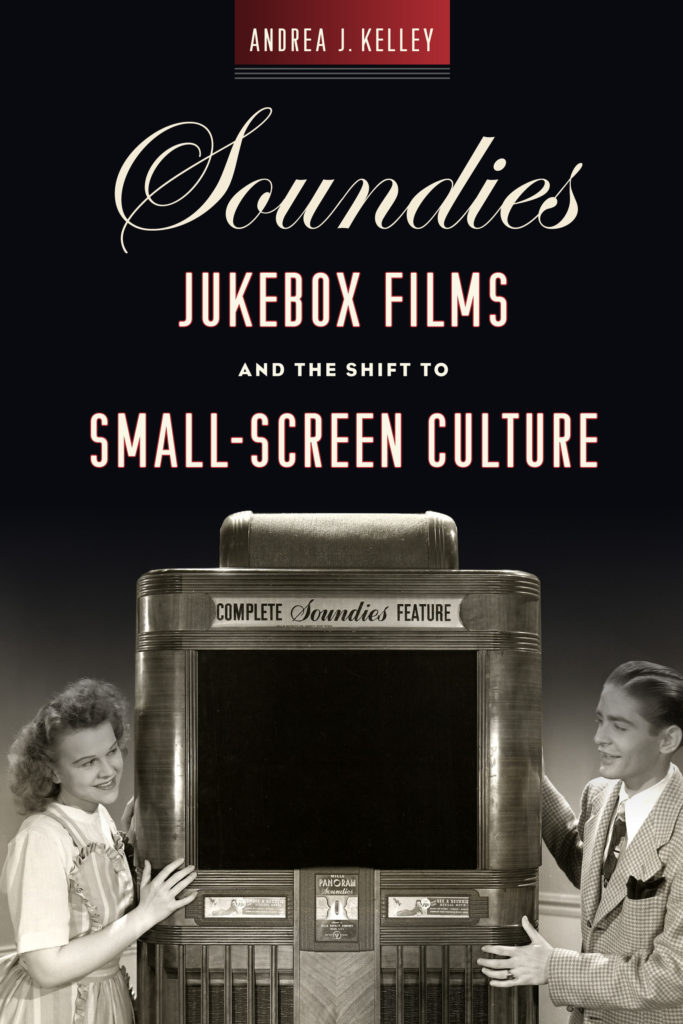

Soundies: Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small-Screen Culture

by Andrea J. Kelley

Rutgers University Press, 2018

Softcover 181 pages $ 26.95

ISBN # 978-0-8135-8633-5

by Betsy A. McLane

Open the cover and jitterbug your way back into “music videos” of the 1940s via the pages of Andrea J. Kelley’s Soundies: Jukebox Films and the Shift to Small Screen Culture. She admirably succeeds in describing the business methods, aesthetic attributes and social history of the coin-operated “Panoram” machine and its black-and-white 16mm musical shorts, called Soundies.

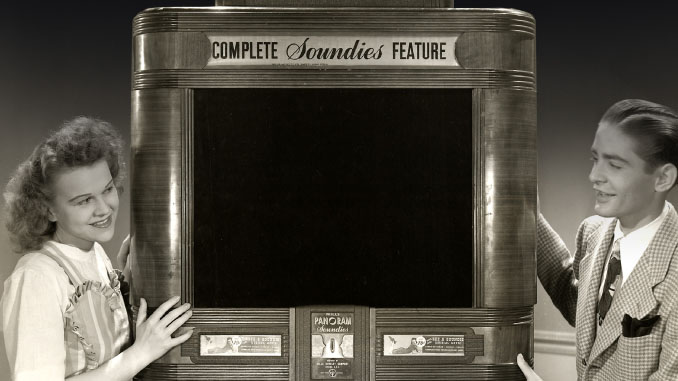

During its heyday from 1940 to 1946, hundreds of Soundie reels, each holding eight films, were circulated to roughly 3,500 Panorams located throughout the United States. Situated in bars, restaurants, train and bus stations, military bases (during World War II), war plants and even at war bonds rallies, Panorams were a novelty entertainment experienced mainly by urban dwellers. Heavy, refrigerator-sized machines, they were both complicated and unique, deploying a closed loop of film, printed backwards for rear projection, onto a 17 x 22.5-inch screen that was integrated into the front of a walnut cabinet. Fortunately, Panorams sat on wheels.

As Kelley describes it, “The screen displays flashing lights when not in use to attract viewers. and a scrolling marquee that lists the song titles and artist names from the particular reel in play. It also boasts an RCA amplifier for controlled sound, an air-conditioning unit to cool the film and a counter to track usage.” The system reportedly later served as the basis for RCA’s 16mm projector.

The main focus of Soundies is to locate the Panoram and its films as an interstitial form of entertainment that both drove and reflected Americans’ transition from the large screens of theatres to the smaller screens of 16mm, to the still smaller screens of television, to the 21st century’s tiny mobile phone screens. Correlatively, Kelley identifies the Panoram as a media phenomenon that occupies a fleeting, but significant stage, not only in reducing the number of people who look at a screen at any given time, from crowds in cinema palaces to single-person viewing, but also in shifting moving image entertainment consumption from public to private spaces. Along the way, she explores the visual jukebox’s pay-for-play business model, as well as the films’ content, meaning and production techniques. She makes a convincing claim for how the Panoram presaged development of visual styles best suited to small screen entertainment.

Soundies have been described by Nigel Bewley of the 1940s Society, a British website, as “glorious little time capsules of music, social history, dance styles, fashions and modes from a seemingly carefree America of the 1940s.” Content in the earliest Soundies was often a replay of bandstand performances of the type common in Hollywood films of the 1930s, such as the Warner Bros.’ Vitaphone shorts — Artie Shaw’s “Begin the Beguine” (1938), for example (www.youtube.com/watch?v=vVr5Nev-enw). These consisted of mostly long shots of bands with a leader and/or singer in front, with occasional shots to an instrumental close-up. Although bigger name talents performed, many were little known. And a few, like Lawrence Welk, became famous enough through Soundies to make the transition to television star (www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2DiIFL-QRY).

The Soundies changed drastically in August 1942 when the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) went on strike, refusing to make new records, which were replacing live performances on radio. Kelley does not go into details about the strike, but its ban caused Soundie producers, already facing a wartime shortage of raw materials for building Panorams, to scramble. Led by union president James Petrillo, the strike was called chiefly to obtain musicians’ royalties for the records’ radio play. The 1942–44 musicians strike remains the longest in entertainment history (www.swingmusic.net/Big_Band_Era_Recording_Ban_Of_1942.html).

The makers of Soundies turned to musicians not affected by the strike, especially African-American and Country and Western performers, many of who were non-union and recorded for labels like Decca and Capitol, which were not affected by the strike. Some instruments, such as the banjo and harmonica, were also exempt from the ban, as were vocalists and novelty comic acts. These performers began replacing big bands in Soundies. As Kelley writes, “A typical Soundies reel during the ban might feature as many as three vocal acts by lesser-know artists [like the Song Spinners and the Smoothies; www.youtube.com/watch?v=A58Iavr9BJ4], two musical dance acts (one usually black-cast), a comedy song (often hillbilly), a big band Soundie reissue and an old film excerpt.”

While black Soundies often reinforced racial stereotypes, as in 1944’s Jukebox Boogie (www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu81QJtaRSo), Kelley argues that they also opened American audiences to new sounds and the acceptance of multi-racial entertainment. One black performer who used Soundies as a road to stardom was Dorothy Dandridge, perhaps most famously in 1942’s Cow Cow Boogie (www.youtube.com/watch?v=xovmaG9S0sQ). Dandridge starred in several Soundies, all of which feature her ever-moving female form and engaging screen personality.

The author points out that while black-cast Soundies may have presented a black culture that 1940s white audiences wanted to see, these short clips also “ask what does it mean to perform blackness in film through an iconography marked by whiteness and masculinity to embody burgeoning social possibilities while having to work within the readily available roles that are marked by oppressive politics of both race and gender.”

This book is a revised version of Kelley’s PhD thesis, and is considerably more compact and far more readable than most such efforts. Her writing is clear, relatively free of film theory jargon, but is still grounded in good scholarship. Soundies’ principal weakness is some repetitious content of the “state the thesis/prove the thesis/restate the thesis” type. Although often demanded within academia (Kelley is an assistant professor at Auburn University), general readers may wish for less repetition and more information about the films’ performers and songs.

Soundies is an especially enjoyable read when instant Internet access is at hand. Most of the titles Kelley discusses are available on YouTube, so it takes only seconds to find audio-visual gratification to complement the text. Watching the films as one reads about them is particularly compelling as Kelley parses the ways that Soundies content crossed racial and ethnic boundaries by highlighting the talents of African-American performers.

There are photographs, mainly from AMPAS’ Margaret Herrick Library, which houses thousands of items related to Soundies history, and Kelley relies mainly on original resources: movie and coin machine operators trade publications. This makes her work as historian and cultural interpreter very credible.

Kelley parses the ways that Soundies content crossed racial and ethnic boundaries by highlighting the talents of African-American performers.

There are few other books on this subject, including The Soundies Book: A Revised and Expanded Guide (iUniverse, 2007) and The Soundies Distribution Corporation of America: A History and Filmography of Their Jukebox Musical Films of the 1940s (McFarland, 1991), both of which provide lists and indices of the films and performers. But Kelley’s work is the only text that provides cultural and aesthetic contextualization. Her book also details the demise of Soundies as they moved to early television broadcast, and as the Panorams themselves found their way into arcade peep shows in the 1950s and ’60s

A warning to readers of this book: If you are fond of 1940s big band swing, have a taste for WWII-era cheesecake on parade, fascinated by original Lindy hoppers, or simply want to see the Delta Rhythm Boys’ smashing zoot-suited 1941 version of “Take the A Train” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=pY2VEPC0eW0), watching Soundies may become addictive. There are dozens of hours online to draw one in, and if they truly take hold and something more authentic is needed, head to the Internet and buy 16mm Soundies advertised as, “Program-1940-1944-Lot-of-14-films-B-W-16mm-Sound-LOWER-PRICE-SALE” on EBAY.

Happy listening, watching and reading!