by Michael Kunkes

The San Francisco Bay Area experienced something new in serial killers during the years 1968-1970. He came out of nowhere, did his work quickly, and left no trail of physical evidence. He called himself “Zodiac,” and his methods in many ways matched the completely tapeless post-production workflow conceived by director David Fincher and editor Angus Wall for their new film.

Zodiac, the docudrama on the unsolved manhunt to apprehend the mysterious murderer, was produced by Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures, and opens nationally via Paramount March 2. It features an ensemble cast, including Jake Gyllenhaal, Robert Downey, Jr., Mark Ruffalo, Anthony Edwards and Chloë Sevigny.

Wall’s association with Fincher goes back to Propaganda Films, a pioneering music video and commercial company co-founded by Fincher in 1987. Wall, working in the company vault, was cutting together directors’ reels while Fincher was directing spots for clients such as Nike and Coca-Cola, as well as videos for Michael Jackson, Madonna, Sting and others. Wall later edited the main title sequence for Fincher’s Se7en in 1995. He was credited as an editorial consultant on 1999’s Fight Club, and his professional relationship with Fincher greatly expanded when he co-edited the director’s Panic Room, his second feature, in 2002. The editor began working on Zodiac in September of 2005 and locked the picture almost exactly a year later.

At the heart of the production was the Thomson Grass Valley Viper FilmStream 2K camera. Fincher had already shot numerous TV commercials with the Viper, but the director and Wall wanted to create an entirely new kind of moviemaking for Zodiac, one that kept the post process––editorial, storage, color timing and correction and visual effects––entirely under their control with a minimum of staff and expensive equipment. And with a reported $85 million budget, Zodiac is the first major Hollywood feature with this workflow to be shot and captured using totally uncompressed 4:4:4 full-range RGB.

“Stylistically, Zodiac is much more All the President’s Men than Dirty Harry” – Angus Wall

The actual shooting of the film consisted of the acquisition of over 18 million DPX (digital motion picture exchange) digital files––shot by cinematographer and longtime Fincher collaborator Harris Savides, ACS––placed onto S.two DFRs (digital film recorders), using the company’s D.Mag (Digital Film Magazine) drives, each of which could hold up to 33 minutes of uncompressed digital material. Those 18 million DPX files ultimately represented 144 terabytes of storage, the approximate equivalent of 1.6 million feet of film––enough for Peter Jackson to shoot another The Lord of the Rings sequel.

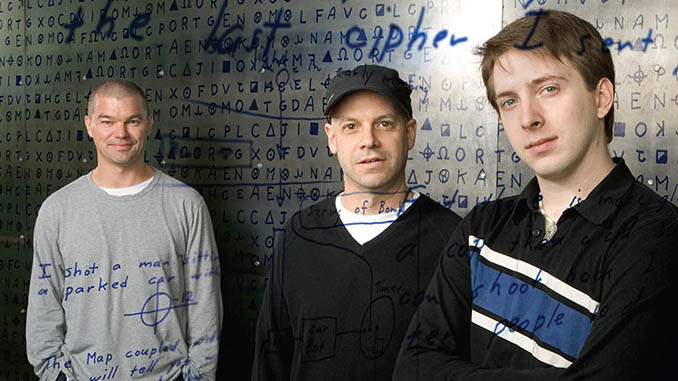

The lean and mean team assembled by Wall for Zodiac included assistant editors Peter Warren, Brian Ufberg and Wyatt Jones. Once production filled a D.Mag with thousands of DPX frames, it was delivered to Jones, who became the keeper of the digital files throughout the production. The frames were pulled from the D.Mags onto a 34 terabyte X-SAN network using a machine called an F-Dock. Two LTO Technology LTO-3 archives were made of these DPX files, which Jones then put through a bit-by-bit verification process.

“Any camera original––whether film or data file––represents the efforts of many people and a lot of money, time and thought,” Wall explains. “It would be stupid to lose any of it, so job one was maintaining the integrity of the data. And ultimately, not a single frame was lost.” After verification, the D.Mags were wiped clean and returned to the set for re-use.

To create editable media, these frames were converted to DVCPRO HD in Apple’s Shake program, where a basic LUT (look-up table) was also applied. All metadata, including script notes, was preserved and added to a MYSQL open-source database that became the central nervous system for the project. After that, Warren synched the DVCPRO HD media to Aaton Cantar-X digital recorder audio files. The merged DVCPRO HD media was then passed off to Ufberg for multi-clipping, script notes and final organization before being given to Wall for cutting––which was all done on Final Cut Pro 5 to take advantage of its native HD abilities and multi-clip features. It was there that the creative process began.

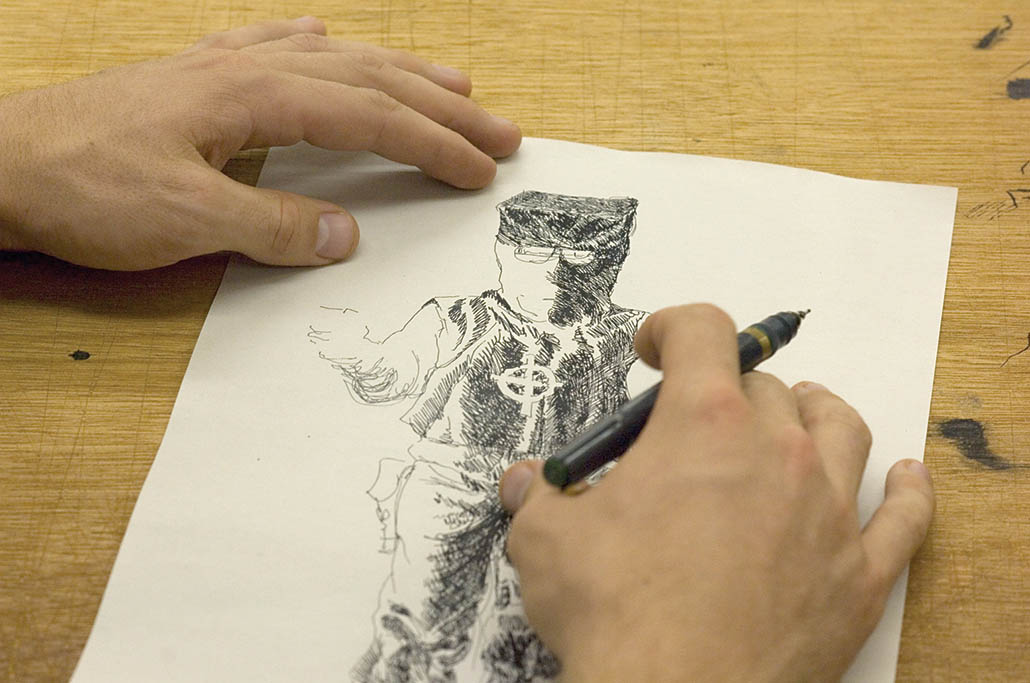

“One of the things that drew me to Zodiac is that the story stuck to real events as much as possible––right down to its attempts to replicate original conversations,” Wall reveals. “The character of Zodiac is quite bizarre and unique, especially in the way he taunted police and the media with his handwritten letters, codes and phone calls.”

Zodiac is based on the books Zodiac and Zodiac Unmasked by Robert Graysmith (portrayed by Gyllenhaal in the film), the San Francisco Chronicle cartoonist who pursued the case for years, long after the trail grew cold. Zodiac the movie is actually two stories. The first section, around the first 45 minutes, covers the series of seemingly random killings that terrorized the Bay Area for nearly two years. Then, Zodiac turns into a detective story for the remainder of its 151-minute (at press time) running time, tracking the effects the hunt has on the lives of the police and newspapermen trying with increasing frustration to find a suspect.

“Stylistically, Zodiac is much more All the President’s Men than Dirty Harry [which was loosely based on the Zodiac murders, but with a wish-fulfillment Hollywood finish]. What I love is its grounding in detail; its specificity. Truth is definitely stranger than fiction, and it always makes a story more interesting and complex.”

Wall points to two favorite sequences. “For obvious reasons, I like the tension of the murder scenes, but I also loved the scene late in the movie between Graysmith and Toschi [Mark Ruffalo],” he says. “It’s basically just the two of them sitting in a booth in a diner. There is a muted emotional resolution to the scene, which gives the two characters some measure of closure. That scene is followed by Graysmith going to see the man he thinks is the killer, Arthur Leigh Allen [John Carroll Lynch], in the hardware store where he works, which is the obvious emotional payoff of the movie.

Demonstrating its resourcefulness, the team was able to create a render farm entirely from off-the-shelf computers.

“David’s movies are often about dark subjects, but they aren’t without levity,” Wall continues. “It would be a mistake to think of Zodiac as a slasher movie. Rather, it’s about the lives of people who are pursuing a killer who is still unidentified today.”

Zodiac’s main creative challenge was the effort to make the story feel alive, while telling it as efficiently as possible, according to Wall. “The story spans a lot of time and the script is long, but every scene contains information that is relevant,” he says. “Lifting a scene always threatened to dislodge a thread of information that would be paid off later. It was also very important to respect the veracity of the material, so any restructure or lift was considered in those terms as well. David went to great lengths to respect the story and the people in it.”

To keep everyone involved on the same page, the team utilized PIX (Private Internet Exchange Firewall) a sophisticated permission-based FTP interface that allows different users to view material depending on levels of access. PIX was also used to get material to the Northern California-based sound team, including re-recording mixers David Parker and Michael Semanick, and composer David Shire in New York.

In this rarified post environment, color correction of dailies was also done very differently. Using a demo version of Apple’s Final Touch software, the team created nine LUTs for use on the footage. “David went into production with these nine LUTs and, instead of creating more, eliminated all but one,” says Wall. “This single-color setting was used for 95 percent of the dailies. This is not only a testament to David and Harris’ ingenuity, but also representative of digital photography––where you immediately know on set what your image looks like without the overnight anxieties of film. With a file-based workflow, color correction can be more like editorial––you can consider your choices instead of waiting for the end and making hurried decisions.”

A digital conform tool was created that proved invaluable. It gave Jones the ability to conform the movie automatically on the SAN (storage area network) and allowed changes to be made instantaneously without ever having to leave the edit bay. “When a sequence was ready to be conformed, I would break it down into one layer of video on the timeline and export an .xml document,” says Jones. “From that, I would run a script through the online database that would create a large tape batch. I would then load up our scalar and pull in all the DPX frames we needed for each sequence, with a ten-frame handle. Finally, I’d run a separate script which created a frame-accurate conform of all the DPX files.”

Demonstrating its resourcefulness, the team was able to create a render farm entirely from off-the-shelf computers. “On the second week of shooting, David pulled out a second Viper camera and it never went back,” says Wall. “An X-Serve render node was benchmarked against a Mac Mini and we discovered that the Mini did 50 percent of the work at 10 percent of the cost.” The team’s total render farm was four Mac Minis and six G5s, which also doubled as workstations for Final Cut Pro, Shake and other applications. “We kept up with production despite the fact that there was a lot of footage [one set-up had 67 takes],” Wall continues. “But David had very specific ideas of the performances he wanted, which meant that he shot a lot.”

Compared to effects-laden blockbusters, contained only some 380 visual effects shots––mainly splits, comps and bluescreens. A total of 13 vendors, large and small, contributed shots, with Jones contributing about 20 himself. “When an effects shot was needed, I would grab the timecode from FCP and prep a log to accompany the files to each vendor,” he explains. “Next, I would trace back the LTO, on which the files lived via our online database, and the previously uploaded D.Mag information. When the vendor returned the shots, I would ‘bake’ the modified DPX files back into QuickTime media and go over them with David and Peter, before plugging them back into the offline.” After a visual effects shot was approved, Jones would bring the sequence of DPX frames into Shake and do a difference matte with the original frames, basically checking the vendors’ work to ensure quality.

With the entire film being done by a small group of people, everyone’s jobs were interlinked. In simplified terms, Jones processed the picture dailies from the D.Mag, and verified that each frame was copied to a back-up digital tape. Warren processed the sound files from Cantar files using Majax and BWF-XML Pro to keep the timecode intact. He would then sync sound and picture, an intricate proposition, since Fincher eschews the use of a smart slate or clapperboard so as not to disturb the actors. He would also prepare and organize the footage for the studios, the director and for Wall.

“One of the things that drew me to Zodiac is that the story stuck to real events as much as possible––right down to its attempts to replicate original conversations,” – Angus Wall

Of the three assistants, Ufberg’s role was the most traditional. “I inserted notes from the script supervisor’s line script––which were important to the cutting choices––adding shot descriptions and other database info and grouping multi-camera shots together. This was a little different because to make those shots work for FCP, we had to export and then re-import the QuickTimes to unify the sound with the picture as one QuickTime unit in order to maintain the sync integrity of both the A and B Viper cameras. This was a major setback in terms of turning over reels to the sound department, but we got through it.”

Warren and Ufberg further broke down the dailies to create line-grouping breakdowns to assist Wall in performance choices, with each set-up created as a separate sequence with anywhere from three to ten line groupings. For preview screenings, the pair would line up the conform against the FCP offline to check for accuracy and make the D5 master.

“Coming from TV commercials, the pioneering workflow combined with the grandeur of the project was a little intimidating to me until we got into a flow with it,” Warren recalls. “We never actually executed the plan until dailies started coming in, so it really was ‘learn as you go.’ My main duties were taking the BWF [broadcast wave format] audio files that were recorded on set with the Aaton Cantar-X and getting them into the system so we could create an xml (extensible mark-up language) of the files that was then imported into FCP.” Once the xml was in FCP, Warren would organize the video dailies and sync with the BWF wave audio files.

Wall had nothing but effusive praise for his assistants: “The challenge each day was to keep up with production. I was blown away by how diligent everyone was and how well it all went. Brian, Pete and Wyatt made this movie. They brought multi-tasking to a new level. We didn’t lose a single frame and the show was finished without incident. For me, it was exhilarating to have those kinds of tools.”

Wall credits Fincher for the ultimate success of the workflow. “The sole reason this process worked, and that we were able to run with it as far as we did, was David. He just reassured everyone that even though there wouldn’t be any film to hold, there would be a movie to show.

“This is the future of moviemaking, and we’re just at the beginning,” Wall concludes. “There is so much potential for making the entire production and post process simpler, better and less expensive.”