Kevin Lewis, photographs by Diana Mara Henry

Though Ken Burns has been accused of a very personal vision of the American experience, his scholarship on his films’ subject matter has elicited a renewed interest in television viewers on the cultural and historical aspects of the American heritage. Which is remarkable because Burns is the first to point out that he is not a trained historian. He developed his interest in history through his appreciation of photography at Hampshire College in Massachusetts.

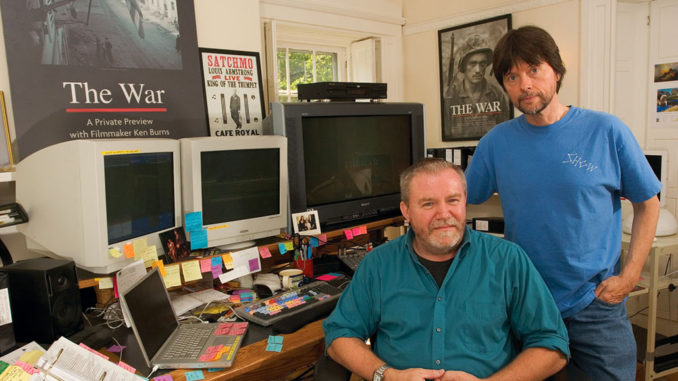

Burns has always acknowledged the large part Paul Barnes, his chief picture editor, has played in the smooth operation and artistic prominence of Florentine Films. From the day Barnes began his association with Burns on The Statue of Liberty in 1985, the two have operated like in-sync duo pianists. Barnes won his Emmy Award for Burns’ Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson (2004). Both speak of each other with great respect, perhaps because Barnes knows the extent of Burns’ genius as a decisive producer as well as a director, and Burns knows that Barnes always has a well-thought-out reason for an editing decision. The two have apparently never had a documented disagreement.

Though Barnes began his editing career at New York University, Burns changed the course of his editor’s life forever when he brought him to Walpole, New Hampshire, a small town in a Norman Rockwell-like landscape where Florentine Films is located. The white clapboard houses which comprise the Florentine studios are unobtrusive and unmarked because Walpole frowns upon signage. Both the producer-director and his editor prefer the rural topography to the urban frenetic atmosphere.

Burns and Barnes invited CineMontage to Walpole for these interviews and to see why they choose to create in this rural tranquility with their production and post associates, most of whom have been with Florentine for two decades. Burns was finishing post-production on what he considers his most ambitious project––The War––the seven-episode documentary on World War II, which premieres on PBS September 23.

The War chronicles the lives of 40 men and women, from four geographic regions of the United States, who served in World War II. At the request of the American GI Forum and the Hispanic Association of Corporate Responsibility, an additional three segments consisting of interviews with and content about Hispanic and Native American veterans were photographed for the film a few months ago by Florentine. The new segments, comprising nearly half an hour of footage, have been included in The War at the end of Episodes One, Five and Six, prior to the closing credits.

“If the film is a success, the editor is due a great deal of credit. It doesn’t mean that the director wasn’t there for every shot, but it quite often means that the editor has saved the production from many of the problems that occurred from shooting.” – Ken Burns

KEN BURNS

CineMontage: The range of your documentaries has been the envy of the industry. You have made documentaries on the suffragette movement, jazz, baseball, boxing, the Civil War, the American Revolution and now World War II, to name just a few. Did you choose these subjects for their variety?

Ken Burns: I think they have all been picked artistically; they picked me, really. I don’t have any clients. We make these films for ourselves. Sometimes an idea can come from outside, but the acceptance and development of that idea is entirely independent and without any commercial pressures.

We don’t say, “Let’s make a film about Elizabeth Cady Stanton; that will make a lot of money.” It doesn’t work that way. We do it because we are drawn to the story. Because Paul Barnes, during every day of editing The Civil War for six months, kept talking about a book he was reading on Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was so interesting that it animated our lunch discussions––and I finally said, “We’ve got to do this film!”

CM: You make extensive use of home movies in both The War and the upcoming film on the National Park Service, which dramatizes the personal connection of the average viewer to great events.

KB: It’s an interesting acknowledgement that there is something essentially authentic, real and true about these experiences that the often carefully composed, professional films lack. Now, in the age of mechanical reproduction, in an age of the ability to manipulate imagery, what is true anymore? We sometimes find in these crude home efforts a sense of a trueness. That’s why YouTube is so successful. That’s why the voyeurism of personal websites that focus on people doing ordinary things becomes important because we know it is unmediated.

“We have insisted on it being an experiential film by taking out our fascination with celebrity and the larger strategic issues” – Ken Burns

CM: Most documentaries are not made union. Why do you use Guild editors?

KB: Two words: Paul Barnes. Paul was a member of the Guild and we honored his participation in that and his and our desire to have a happy shop. We tend to employ people for long periods of time. Often the expense has been difficult for us, but what we have bought in return––and that sounds a little bit crass––is a level of competency, expertise and genius that has made our films immeasurably better.

These films are made in the editing room––not just with editors, but with the producers, writers and filmmakers engaged in an incredibly important process. At the heart of that has been our ability to translate our vision to the men and women who cut the film.

CM: In looking at your films, it’s evident that you understand the important contribution of the editor.

KB: In the case of film editing, if the film is a success, the editor is due a great deal of credit. It doesn’t mean that the director wasn’t there for every shot, but it quite often means that the editor has saved the production from many of the problems that occurred from shooting. We know the extent to which the editors are a huge and important part of our success. And that’s in a film where I can sit over them and sign off on every cut.

I still don’t deny the primacy of the director, but we live in such a celebrity culture that people are always trying to focus on one person. When in fact, what is so great about this medium is its collaborative nature: writers with cinematographers with editors with other producers and directors. We’re happy to have it be a family and not individually run, because that belies the truth of film production. It takes a lot of people.

“We make these films for ourselves. The acceptance and development of that idea is entirely independent and without any commercial pressures.” – Ken Burns

CM: Are you using directional sound more in your sound editing now that you have more tracks with digital sound?

KB: Yes. Whereas on the Steenbeck, you would have one, two, three tracks, if you were lucky. So, you had your dialogue track, your music track and a rudimentary sound effects track. And that was it. Now, you’ve got several tracks of sounds, and you can mess around with that. It’s just a wonderful thing.

CM: You have emphasized the fact that The War is about ordinary people in extraordinary times. Is The War a more personal, intimate film than previous World War II documentaries? Did you strive for what Robert Warshaw called “the immediate experience” of a film?

KB: We have insisted on it being an experiential film by taking out our fascination with celebrity and the larger strategic issues––I’m not saying we are not aware of what the purpose of the battle is or what the overall situation is––by not spending so much time on it, which permits us to make the battles come alive. So we take this silent archival footage and spend literally years making it come alive so that people jump out of their seats. Not because the plane whizzes overhead or the bullet zings by their heads, but because of the horrible immediacy of this war, which we refer to as a “good war,” but which is, in point of fact, the worst war ever in terms of death and loss.

PAUL BARNES

CineMontage: You started editing student films at New York University and were influenced by the feature film editor Carl Lerner [Klute, 1971] and the documentary editor Lawrence Silk [Marjoe, 1972]. Both taught editing at NYU. What did you learn from them that prepared you for your career?

Paul Barnes: The combination of those two people opened up so many doors for me in terms of what editing is all about––from both the feature film and documentary standpoints. By having their classes back-to-back, I could see how you could actually mix it up a bit. The tricks from features you could apply to documentaries and vice versa. And often, they used the same tricks; it didn’t matter what the form was. I cut student films based on what I had learned from Carl and Larry.

“To live with this material for over two years has been the most emotionally taxing job I have ever done, because I was watching this grueling footage of World War II over and over again.” – Paul Barnes

CM: How do you like to edit?

PB: Personality wise, I’m more suited to working one-on-one with the director or working in the dark alone. I have the introverted nature that many editors have. I can be very concentrated and very Zen-like, and once I start cutting, I have no problem with that.

CM: Your career has been primarily with one filmmaker––Ken Burns––and he regards you as a collaborator. Has there ever been a situation where he wanted to include shots that you regarded as interference with the narrative?

PB: [laughter] That issue has never come up with Ken, to be honest with you. There are shots that he has directed, that he has even shot himself, that he falls in love with… But the one thing about Ken is that he is not only a good director, he’s a terrific editor too. Even though he falls in love with a shot, if it doesn’t fit somewhere, he’s the first one to say, “Don’t use it.”

In that regard, he’s like me in that he’s very decisive, which I really appreciate. That’s one reason I have loved working with him all these years. The editor becomes like a father confessor, a psychological counselor in some ways, to a director. But that doesn’t take away from the greatness that he deserves.

CM: How would you describe your working relationship with your editors?

PB: My two co-editors, Erik Ewers and Tricia Reidy, are both terrific [see related story]. Erik actually began with us as an intern, then became an apprentice, then assistant and finally a full editor. On The War, Erik––who cut three shows out of the seven––has really come into his own as an editor. Some of the most extraordinary editing of the entire series are in his three shows. His passion for this film has been overwhelming. It has been so gratifying to see him grow over the ten-year period he has been with us. I’m supposed to be the supervising editor, but I don’t have to tell him anything.

Or Tricia either. She was an intern on The Statue of Liberty and came up through the ranks, becoming an editor on The Civil War. She does a lot of freelance editing on her own and has not worked with us as much as Erik has, but whenever we feel that we need another great partner, we pull her in. The thing about Tricia that I love is that she is as stubborn as Ken, and uncompromising when she thinks something doesn’t work. She’s also wonderfully vocal about letting her opinions be known. If anyone can sway Ken off something that doesn’t quite work, Tricia can. He’ll listen to her even more than he will listen to me, which is terrific. She’ll just sit there and say, “That’s terrible.” She cut Episodes Four and Seven of The War.

“I grew up in a union family; my dad and my uncle were strong supporters of unions. Being a member of a union is ingrained in me.” – Paul Barnes

CM: What editing system do you use?

PB: We are using an Avid system 9000. It’s about six years old, but it still works for me. I’m not a big tech-head. I rely on my assistants and we have a tech director here who installed the equipment.

CM: Ken Burns has an elegiac style with a philosophical narration. Do you find that present in The War too?

PB: What you will see in this film is a lot of battle sequences that have immediacy. They are not elegiac at all. You feel like you are right in the middle of the action. We had all of that stock footage to use.

CM: Have you had trouble with the digital conforming of the old newsreels or World War II Signal Corps footage that was shot at different speeds?

PB: Every once in a while it becomes a problem, but one of the beauties of the Avid is that we can play around with the speed. So if something appears too jittery or too fast, we can slow it down, if that is what we are trying to achieve. Avid has variable speed control that we can apply to various shots, and I actually appreciate that.

On Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, for example, the footage was very old, from 1908 or 1910, and some of it was speeded up. I found myself playing around with various speeds and we arrived at something that worked quite well.

“The one thing about Ken is that he is not only a good director, he’s a terrific editor too. Even though he falls in love with a shot, if it doesn’t fit somewhere, he’s the first one to say, ‘Don’t use it.'” – Paul Barnes

CM: How did you deal with that problem in the pre-digital era?

PB: Previously, it became quite costly and the footage had to be sent to an optical house. To reprint it took so much experimentation with various speeds to finally arrive at a result. Oftentimes, because it was so costly, producers would say, “Forget about it; we’ll live with it.”

CM: Has The War been a different experience for you than your other projects?

PB: The War is a 14-and-a-half-hour film in seven parts. To live with this material for over two years has been the most emotionally taxing job I have ever done, because I was watching this grueling footage of World War II over and over again. I was trying to make sequences work, and imagining whatever happened to those men at that time. I was also wondering about what is happening in the world now, and I don’t think there was a day when I wasn’t wondering about the men in Iraq.

So in terms of editing it––and living with it––this project, more than any other, was emotionally very draining. At times, when I was cutting the Holocaust sequence, I actually had to get up and leave the room because it was so hard to watch that stuff and try to put it together.

“What you will see in this film is a lot of battle sequences that have immediacy. They are not elegiac at all. You feel like you are right in the middle of the action.” – Paul Barnes

CM: What other kind of gruesome footage were you dealing with?

PB: Unlike other World War II films, our researchers worked with outtakes of the Signal Corps footage, especially in the South Pacific battles. The outtakes were so graphic and so grueling to watch. It was so startling to us that cameramen had even caught that kind of material. We were all under the impression that they were kept away from the front lines, or were told not to shoot dead bodies. The official films made by the Marines and the Army didn’t use that footage, but we had access to all the outtakes from the Library of Congress––we saw all this footage of men ripped to shreds.

CM: Apparently, you are the reason that Florentine Films uses Guild editors and post-production personnel. Can you talk about why?

PB: I grew up in a union family; my dad and my uncle were strong supporters of unions. Being a member of a union is ingrained in me. When I got into editing, I was freelancing at first. But when I did get into the Guild, one of the first things I would say in negotiations with producers is, “I want to go union with this.” Early on, I was rejected left and right, because producers kept saying they had no money. But eventually, I got a bigger reputation and bigger budgets and I was able to talk some of these producers into doing it.

Ken was one of them, and he didn’t really have any problem with it. I started with him on The Statue of Liberty in 1985. He made his budgets accommodate what our wishes were as editors, and I really appreciated that. There were not a lot of arguments and no long drawn-out negotiations. When he asked me to come to New Hampshire on a full-time basis, my status in the union was something I was really worried about. And when we sat down, I said, “The only thing I really want to do is to hang on to my union membership and continue my benefits”––and that involves putting assistants and sound people on as union––and he has never complained about it.