by Edward Landler • photos by Peter Zakhary/Tilt Photo

On August 12, a beautiful Saturday in Burbank, an eager crowd filled the Walt Disney Studio’s Main Theatre on Dopey Drive, for the tenth annual EditFest LA, presented by the American Cinema Editors (ACE). A show of hands revealed the vast majority of the sold-out audience to be about half editors and about half assistant editors; surprisingly, almost two thirds of the audience were attending this celebration of the art and craft of editing for the first time.

During the day, the attendees were engaged by four in-depth panel discussions featuring some of the best editors in the business focusing on significant issues and concerns of their profession. Designed to share practical insights and aesthetic perspectives in an intimate setting, the EditFest limited the number of attendees to allow for the greatest personal interaction throughout the event.

Introducing the program, ACE President Stephen Rivkin, ACE (Avatar, Pirates of the Caribbean trilogy), welcomed the audience and announced that for the first time, EditFest LA was being streamed online (unfortunately, due to broadcasting rights issues, the film clips screened during the sessions would not be seen online). Rivkin also thanked Jenni McCormick and the ACE staff for organizing the event, and its sponsors, including the Motion Picture Editors Guild, Disney Digital Studio Services, Adobe, Avid and Blackmagic Design.

Just before the first panel discussion, a team from Blackmagic presented a demonstration of the features and capabilities of the new DaVinci Resolve 14.

Women in Editing

Personal Experiences and Challenges in the Cutting Room

Lillian Benson, ACE (Chicago Med, Eyes on the Prize II)

Lisa Zeno Churgin, ACE (The Old Man and the Gun, The Cider House Rules)

Edie Ichioka, ACE (Toy Story 2, Boxtrolls)

Virginia Katz, ACE (Beauty and the Beast, Dreamgirls)

Lynzee Klingman, ACE (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, War of the Roses)

Terilyn A. Shropshire, ACE (Eve’s Bayou, Beyond the Lights)

Moderated by Margot Nack, senior manager at Adobe

Adobe’s Nack began by asking what had inspired the panelists to be editors. A professor in art school told Benson that she had the best sense of sequence the professor had ever seen and asked, “Are you in film?” Later, while teaching art in public school, Benson gravitated to film work. Churgin’s brother-in-law shot a movie in her New York City apartment and she said, “I started exploring what people did in film.”

Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive and art houses were a great education “when there was no Netflix,” said Ichioka. Later, working at a cafe frequented by the crew from the nearby Saul Zaentz Film Center led to her first film job. Katz, whose father was a film editor, admitted to nepotism, while Klingman, who learned to love film from talking about movies at the family dinner table, found out there were jobs in filmmaking when she met a film editor just before she graduated from college. A journalism major at USC, Shropshire moved into the film program where she discovered, rather than shooting and production, “I loved putting together the story.”

Moving past their early careers, the panelists presented clips from their work. Benson screened a sequence from the documentary Maya Angelou and I Still I Rise (2016), a project she came to after the first editor left because “there was not enough Maya, not enough emotion and not enough of her words… This is the scene that convinced producers I knew what I was doing.”

The scene depicts the poet reminiscing about the indignities suffered by blacks in her Alabama hometown. The editor said, “You try to get into the headspace of the character of the historical Maya telling of her joys and pain, and what it’s like to go back to her town.”

Churgin screened the climactic execution sequence from Tim Robbins’ Dead Man Walking (1995) with Susan Sarandon and Sean Penn. Sharing the director’s views on capital punishment, the editor described the process of portraying the senselessness of the death penalty in the case of a horrific crime: “We went through a lot of changes to come to this scene juxtaposing the rape/murder and the execution.”

Noting that this movie was made while post-production was changing to digital, Churgin praised Robbins for adding to its end credits: “This film was edited on old-fashioned machines.”

Instead of screening her recent animation work, Ichioka appropriately brought a sequence from a feature documentary, Murch: Walter Murch on Editing (2007), which she also directed with her husband, David Ichioka. She had assisted the legendary editor and sound designer on The Godfather: Part III (1991) and The English Patient (1996) and “learned an amazing amount from him.”

This was demonstrated in her clip, which moves from Murch describing the impact of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1960) on film editing to the origins of “sound design” in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), including the invention of the term itself.

Reflecting on the transformation of editing technology, Ichioka recalled learning by standing next to editors, handing them the clip they wanted and thinking about it. She continued, “Film is sort of a thought process that maybe isn’t communicated as frequently nowadays where your assistants are down the hall…because they are able to work independently.” Churgin added, “I can’t work independently. I thank every assistant.”

Katz brought a clip from Bill Condon’s movie about the last days of director James Whales’ life, Gods and Monsters (1998), with Ian McKellen and Brendan Fraser. “We had the movie working except for this one pivotal scene,” she said. In the scene, the aging director of Frankenstein (1931) talks with his gardener, seeking to ask him for a great personal service.

“We were searching for one moment and found it — the one cut that says everything in one dialogue scene…just a flash in Ian’s expression,” Katz explained. “There’s something about small, intimate movies that always hold a place in my heart.”

Before introducing her clip, Klingman spoke of her early career — when “all the editors were guys” — working on commercials, industrials and educational films until being hired for the major anti-Vietnam documentaries, Emile de Antonio’s In the Year of the Pig (1968) and, in Los Angeles, Peter Davis’ Hearts and Minds (1974).

Veteran sound editor James Nelson, who also worked on Hearts and Minds, recommended her to Michael Douglas who brought her into dramatic features by hiring her to edit One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). “But I chose a clip from Danny DeVito’s Matilda (1996), because it’s fun,” said Klingman, and the EditFest audience participated in making Bruce Bogtrotter’s humiliation in a school assembly a personal triumph.

With time running out, Shropshire screened a sequence from Gina Prince-Bythewood’s Love and Basketball (2000) centered on a man and a woman playing a nighttime game of one-on-one. The scene was shot over two nights and the editor said, “When the first night’s dailies came in, technically it was all there…but there was something I wasn’t feeling that I knew I should be feeling.”

She continued: “You are the first audience as the editor and it was important to talk to the director about the scene.” On the second night of shooting, Prince-Bythewood got the tight physical shots between the two players, the body exchanges and the close-up looks between them, all contributing to conveying more emotion between the characters.

Breaking Boundaries

Editors Involved in “Game-Changing” Movies

Jacqueline Cambas, ACE (Frankie and Johnny, Mermaids) on Luis Valdez’s Zoot Suit (1981), a seminal work of modern Chicano theatre and film

Robert Leighton (A Few Good Men, The Princess Bride) on Rob Reiner’s This is Spinal Tap (1984), the first “mock-umentary”

Stephen Rivkin, ACE (The Hurricane, Robin Hood: Men in Tights) on James Cameron’s Avatar (2009), the leading pioneer in photo-realistic motion capture, CGI and 3D technology

Paul Rubell, ACE (The Insider, Thor) on Stephen Norrington’s Blade (1998), the first successful modern Marvel movie

Moderated by Michael Krulik, principal applications specialist for Avid Technology

“What made you want to take on the film?” was moderator Krulik’s first question. Cambas replied, “I didn’t know it was a game-changing anything. It was early in my career and I was happy to get a movie.” Based on Valdez’s play about the World War II-era Los Angeles “zoot suit” riots, Universal financed the low-budget project to see if it could produce movies for a limited audience. Although shot on a rotating stage at the Aquarius Theatre on Sunset Boulevard, Cambas said, “Luis wanted it to look real.”

Coming to the United States from England in 1975, Leighton said, “I discovered how to edit by making a lot of crummy movies,” including Stunt Rock (1979), a movie about a rock band. He made the acquaintance of Karen Murphy, who became the producer for Reiner’s shoestring-budgeted This Is Spinal Tap. She asked him to edit the project because she couldn’t find anyone else “who got the idea that it was supposed to be ‘fake’ documentary and it meshed with the type of comedy I knew from England,” he said.

At the higher end of the budget spectrum, Rivkin had just come out of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies when producer/writer/editor/director Cameron asked him to join him on Avatar. When he went to talk with Cameron, the Rivkin found him on set “scouting” a virtual reality world looking at an iPad-like device with handles. He said, “This was one of the wildest things I’d ever seen; if he wants me, I’m in.”

Rubell said, “I didn’t know Blade was the first modern Marvel movie until I was asked to be on this panel.” After editing indie features, he edited 17 TV movies in 10 years and found it hard to get on a theatrical feature being a “TV editor.” When director Norrington asked him to do the movie, he jumped at the chance to get away from television and has never returned.

Cambas’ sequence from Zoot Suit was an elaborate dance number. On her first musical, and with a small budget, the editor had to Foley all the dance footsteps herself, working into the wee hours of the morning and coming in the next day to get just a “Yeah, that was fine.” Krulik asked if she would change anything looking at it now. The editor said, “I still say I should have tightened it.”

Leighton screened a Spinal Tap scene in which disasters pile up as it becomes clear that the band’s American tour is not going well. Shooting documentary-style with the dialogue all improvised, the editor was getting three-to-five hours of dailies every night over five or six weeks of shooting. Committing fully to the joke, he said, “I stayed with just telling the story and dealt with documentary-style overlaps and jump cuts. Cutting on 16mm was a trial in itself.”

The first cut was five hours long; cutting it to its present 82 minutes, he had to lose a subplot about the tour’s supporting band led by the Runaways singer, Cherie Currie. Asked if he would change anything, Leighton said, “It still plays great, but I could see more.” After Spinal Tap, the editor collaborated with director Reiner on 15 more features.

To help describe Avatar’s editing process, Rivkin presented clips showing four different stages of work on one scene. Demonstrating the first editing process based on performance, he screened video reference dailies of captured performances from a two-character scene from the movie. In this first stage of performance capture, the director concentrated on getting the performances from the actors without the usual concern for camera positions and moves; the reference cameras provided a record of the performances to cut with and something to compare to later phases. This was followed by the second clip, an edit of the performances using the best takes with the ability to combine different takes of the actors. This performance edit was essentially a pre-cut for the next stage and was used to prepare the scene for virtual production in which the performances were placed in their setting with character design, sets, props, etc.

The director now proceeded to create shots from performances that were captured sometimes months earlier, concentrating on actual shot composition and creation with the virtual camera. In the third clip, Rivkin showed the edited scene as it was shot with the virtual camera. The editors, including Cameron and John Refoua, ACE, cut as they went along in this second editing process; if they needed a close shot or a medium shot, Cameron just shot at the desired angle and distance with the virtual camera and the performance still worked within it from any angle. Rivkin explained, “As an editor, you always want to start with performance. Then when all the best performances are selected, we can concentrate on actually shooting the scene, the way you would cover any live action scene, but this time without the actors present. Unlike green screen, you see the entire environment.”

The fourth clip was the virtual camera cut of the scene in final render form as it appeared in the film with a picture-in-picture of the original performance alongside. Answering Krulik’s question about changing anything now, Rivkin answered, “I don’t look back and second guess decisions that I’ve made creatively. You have to learn and keep moving forward. That reminds me of an old-time editor once telling me, ‘It only takes two people to edit a film, one to do it and one to say stop.’”

Rubell chose his clip from Blade because it was one of the few action scenes in which Stephen Dorff’s vampire appears. Krulik noted that Blade was the first of the genre to use electronic music and the editor agreed, pointing out that The Matrix (1999) released the following year helped set the trend. Asked if he would change anything, Rubell said, “Some of the action.”

The moderator asked about their “game-changing” movies’ experiences in previews. For Zoot Suit, Cambas said, “People were dancing in the aisles…it happened three or four times.” At previews for Spinal Tap in Dallas and Seattle, people got bored and walked around. Leighton said, “It only became a big hit over the years, at late night screenings.” Neither Rubell nor director Norrington had great hopes for Blade, but the first preview got excellent feedback and the movie went on to box office success.

The early preview cuts of Avatar, said Rivkin, were “a mosaic of performance edits and virtual templates, but people still saw through to the story.” The final changes were edited in 3D and Avatar’s release led to a rush of film conversions to 3D, but the editor said, “Jim believed it should be an element of the story, not the star. Now 3D has evolved and conversions are being done much better, but the ultimate goal is to see it without glasses.”

A question from the audience touched on the technological transformation of editing. Rubell answered, “Try looking at 15 variations of a scene and your head is spinning. Being able to do that is a great thing and a terrible thing.” Rivkin noted, “I loved editing on film, with trims and cuts; it was a pre-mediated process. I still think a scene through before I cut the footage. Now it’s too easy to do and undo without a game plan, but the Avid gives us an incredible tool that archives a historic record of your process.”

Inside the Cutting Room with Bobbie O’Steen: A Conversation with…

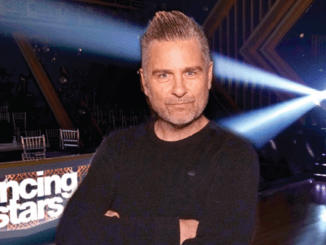

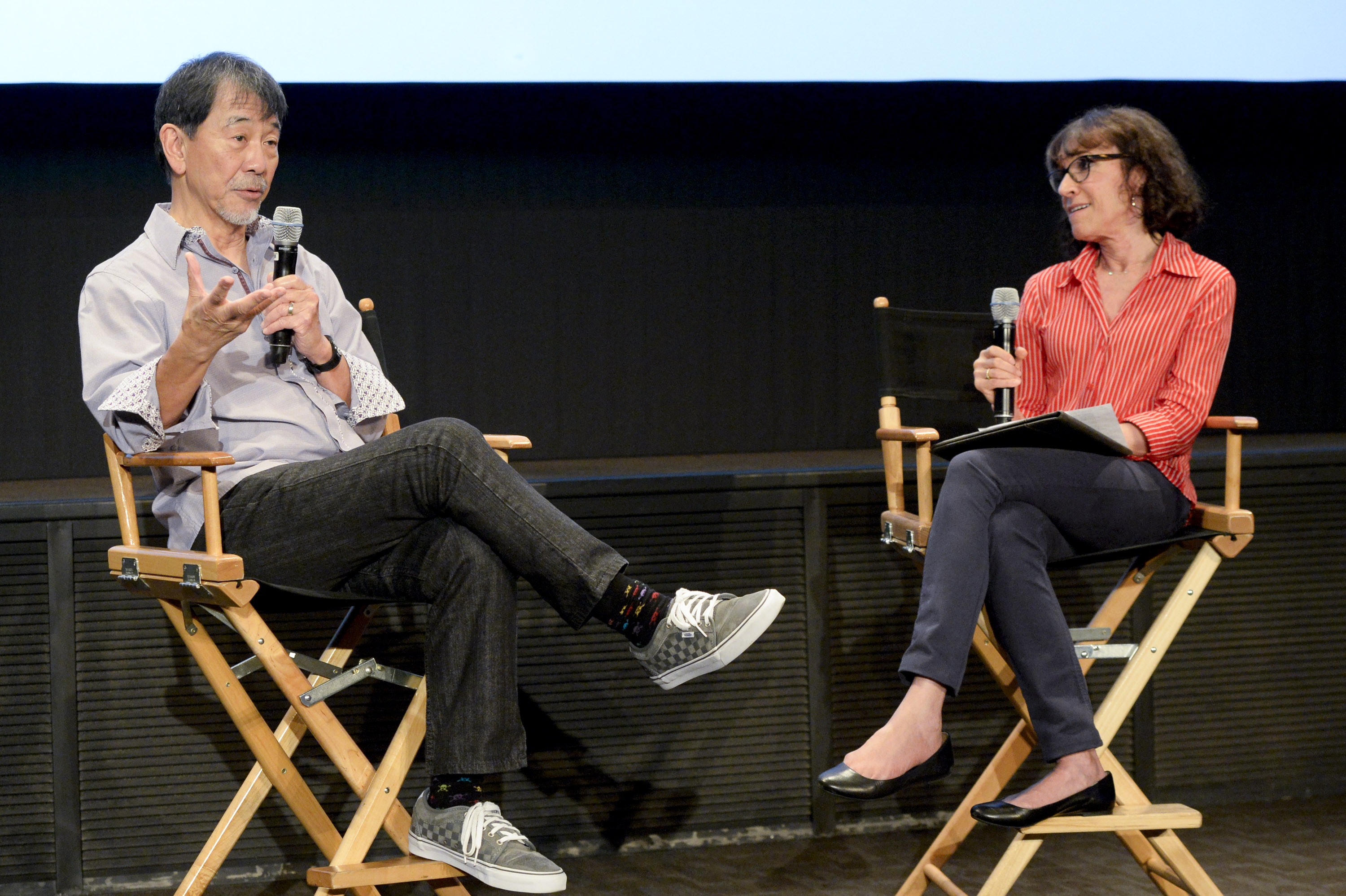

Richard Chew, ACE (Star Wars, Risky Business)

Moderated by Bobbie O’Steen (author of The Invisible Cut and Cut to the Chase)

Suggesting the source of the Chinese-American Chew’s personal social and political concerns, writer O’Steen told of his growth in inner-city Los Angeles, attending LA High and UCLA, and going to Harvard Law School. Then, she said, “You saw a film that changed your life.”

The editor responded, “I wasn’t happy at Harvard Law School; I wanted to find a field that you can feel fulfilled in and achieve a goal greater than yourself in life.” During an “escape” to New York from Cambridge, Chew saw Michael Roemer and Robert Young’s landmark independent film, Nothing But a Man (1965) with Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln. He said, “It was the first film I’d seen about people of color that painted them in human terms. There was something in this medium I wanted to be part of.”

Chew met Young, who helped him get his first job in media in 1966 on a Seattle TV station’s daily news program. He said, “They assigned me a 16mm camera and a hot splicer to make one or two short news stories every day for six months — it was my boot camp.” His first assignment was a 45-second piece about Bobo the Gorilla’s 15th birthday at Woodland Park Zoo.

After shooting and editing The Redwoods (1967), produced for the Sierra Club (which won an Oscar for Best Documentary Short), Chew worked as a cameraman on Woodstock (1970). Another of the film’s cameramen told him about Coppola and George Lucas’ American Zoetrope in San Francisco and he edited documentaries there for John Korty.

Working down the hall from Walter Murch, ACE, CAS, MPSE — who was supervising editor on Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) — Chew was asked to do the movie’s first cut while Murch was doing post sound on Lucas’ American Graffiti (1973). He said, “That’s how I got into features and when I learned all the techniques of nonlinear after working to put linear stories in documentaries.”

As fellow editor Klingman had noted earlier in the day, Chew also edited One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest where, he said, “I learned more from working with Milos Forman. You can use cutaways in a dialogue scene to observe other stories and set up other characters.” Two years later, Chew and Marcia Lucas came in to edit Star Wars (1977), later joined by Paul Hirsch, ACE, and all three won the Oscar for Best Editing. “Another mind-bending experience,” Chew exclaimed. “Marcia taught me how to intercut two or three different scenes to notch up the tension.”

Then moderator O’Steen presented four clips from the editor’s films, representing completely different genres, to explore his specific approaches to film storytelling. In one of his earliest Hollywood films, Richard Benjamin’s broad comedy My Favorite Year (1982), the cutting of the clip deftly presents Peter O’Toole’s Errol Flynn-like movie star as a straight man setting up the laughs for the supporting actors when he visits a Jewish family in Brooklyn for dinner.

Jumping ahead to a sequence from Jessie Wilson’s sensitive drama I Am Sam (2001), a mentally handicapped father (Sean Penn) trying to retain custody of his daughter discusses the trial with lawyer Michelle Pfeiffer. “In a picture like this that tends toward over-the-top moments,” the editor described the ways he found in this scene to cut the shaky camera work used to represent Sam’s sensibility to further counteract the sentimentality of the story.

After showing the scene of Tom Cruise and Rebecca De Mornay on the Chicago “L” train from writer/director Paul Brickman’s darkly comic coming-of-age satire Risky Business (1983), Chew pointed out that the intermittent blacking out of the train lights suggested the use of short fades to connect the takes of the couple making out on the train. When background green screen shots for this scene were scrapped, the editor used them for the mesmerizing title sequence which also added to the reasons they asked the German electronic music band Tangerine Dream to do the film’s music.

The final clip was the scene depicting Robert Kennedy’s assassination from writer/director Emilio Estevez’ Bobby (2006), set entirely on that fatal day in 1968, when, moderator O’Steen noted, Chew himself was politically active. Like the entire film, this sequence intercut its dramatic footage with actual documentary footage. “It was a new creative and technical challenge to work with this older footage,” said the editor. In the scene, he added poignancy by playing Kennedy’s speech after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination from just two months earlier over the chaos in the Ambassador Hotel kitchen.

Regarding his relationship with directors, Chew noted, “The best situation that an editor can have is to have communication go both ways.”

The Lean Forward Moment

Films That Motivated Us to Edit

Lynne Willingham, ACE (The X-Files, True Blood, Breaking Bad)

Kelley Dixon, ACE (Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, The Walking Dead)

Chris McCaleb (Breaking Bad, Better Call Saul, Fear the Walking Dead)

Moderated by Norman Hollyn, ACE, professor, USC School of Cinematic Arts

A yearly staple of EditFest, Hollyn’s “Lean Forward Moment” panel asks editors to share the films that inspired them to be editors, or the films they keep going back to for insights into editing. This year, however, the moderator said, “The panel is also about mentoring. If you’re learning, how to find a mentor; if you’re an editor, how to pass your knowledge along as a mentor.”

Thus, the panel featured three “generations” of mentoring on TV series — Willingham was mentor to her assistant editor Dixon; Dixon as editor was mentor to assistant editor McCaleb, who is now an editor. All three worked on Breaking Bad — “the gift that keeps on giving,” as Willingham remarked.

Hollyn also gave the audience a hashtag to tweet questions to him on Twitter during the session. The moderator’s choice of when to relay the questions made for a free-flowing session.

Dixon chose a scene from Oliver Stone’s J.F.K. (1991), edited by Pietro Scalia, ACE, and Joe Hutshing, ACE. It depicts New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) describing the timeline of activity while showing the Zapruder assassination home movie in court. Intercut with this in Stone’s film is a broad range of footage showing different perspectives, documentary and dramatic, matching the timeline and made to look archival.

Dixon said, “All the sources of footage were bumped to three-quarter-inch tape and cut on VCRs; it was too complicated to be cut on film. They’re using all different types of footage and angles to show memory.”

A Twitter question asked if a film has a thought-out structure or does it emerge from the footage. Making clear that every film is different, Willingham said, “If the director has a plan, you can tell from the footage.” McCaleb suggested that an editor watch every frame of the dailies to see new ways into a scene. Hollyn asked, “When you’re watching a movie, does watching the editing wreck it for you?” “Only if it’s bad,” replied Dixon.

Screening a clip of Mark Wahlberg’s Dirk Digler doing a drug deal in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights (1997), McCaleb pointed out that the way editor Dylan Tichenor, ACE, cut the scene, and what the sound does, suggest chaos. He said, “There’s almost a minute hold on Wahlberg while ‘Jessie’s Girl’ is playing, no cutting at all; that’s very brave.”

Asked how a successful editor keeps learning, Willingham noted that, apart from keeping up with what your friends (other editors) are doing, “Sometimes the best way to learn is to work on something that really is not very good, she said. “It’s hard to make something like that look good.”

She then went on to show the arrival of immigrant Holly Hunter with her piano on a New Zealand beach in Jane Campion’s The Piano (1993), edited by Veronika Jenet. Willingham noted especially how all the characters are introduced and “the country itself is a character.”

With questions on how editors choose assistants, the discussion turned more to mentoring. The panelists all agreed that editors and assistants spend a lot of time together. “You’re looking for a partner, basically,” McCaleb said. “Ultimately, it’s do you click with them or not?”

Focusing on personality issues, Willingham spoke of an assistant who didn’t need to learn from watching her cut, but was not comfortable dealing with the director and the producer. “The thing I did most for her was showing her how to behave in the editing room,” the editor said. Dixon added, “You have to learn how to manage the job and manage the people.”

Recalling advice she received as an assistant, Dixon went explained, “Editor Juan Garza told me, ‘The best way to start is cut a scene a day along with your duties as an assistant; if you can cut two scenes a day in addition to your duties, you’re doing pretty well.’” Dixon also recommended networking as much as possible — but not to count on finding a job that way.

With the session nearing its end, one last Twitter question came in: “How do you incorporate your own creative voice in your work and make it your own?”

“Whatever project you’re working on is your project and what you do imparts your voice,” responded Willingham. “If they have to change more than 10 percent of what you’re working on, you’re not working hard enough…or they’re jerks.”

McCaleb concluded, “Trust your instincts; like Lynne would say, ‘Don’t try to cut it like me.’ Stay open to criticism and take it — but don’t take it personally.”

With that, everyone left the theatre to keep talking about editing outside at the EditFest Cocktail Party on Dopey Drive.