by Edward Landler

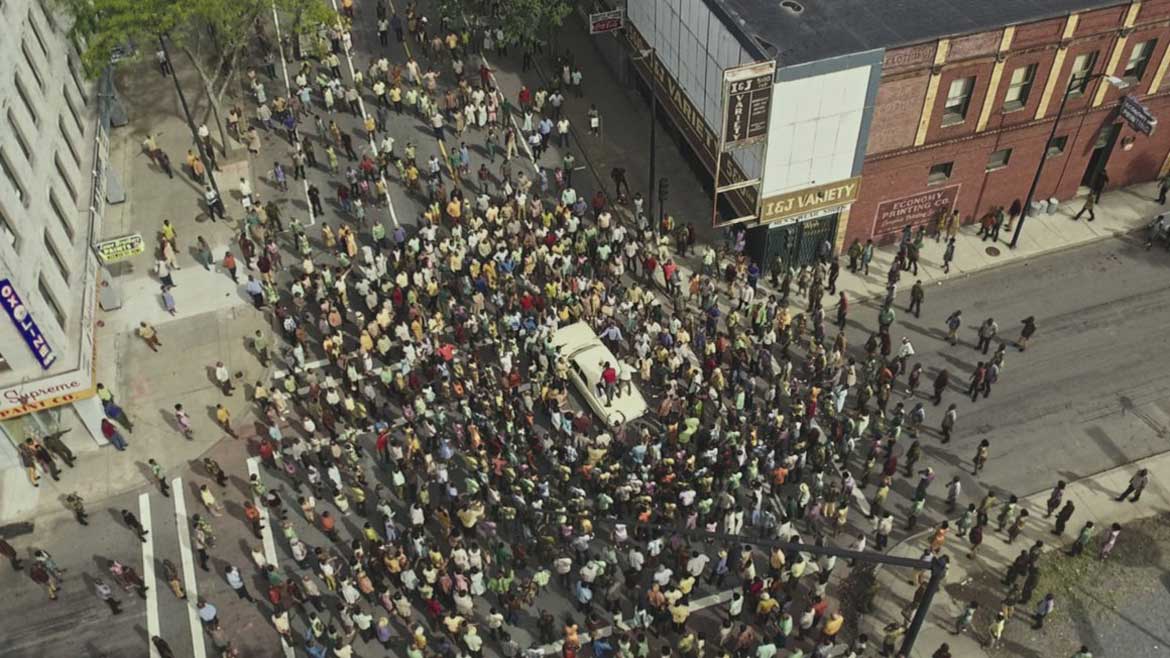

On July 23, 1967, a police raid on an unlicensed after-hours bar in Detroit precipitated five days of major racial violence. A half century later, director Kathryn Bigelow presented a vivid perspective on this uprising and its place in our social history in the film Detroit, released through Annapurna Pictures this past summer. Drawing from extensive documentation, Bigelow and co-writer Mark Boal concentrated on a group of people drawn together at the city’s Algiers Motel during the days of rioting to dramatize issues of economic inequality, police abuse and legal injustice that still divide us.

The film achieves a relentless authenticity through its inseparable union of picture and sound. The cinematography of Barry Ackroyd, BSC, creates the same tense, mobile immersion in the moment that he brought to Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008), while the work of supervising sound editor/sound designer/re-recording mixer Paul N.J. Ottosson, CAS, places the viewer within the scene.

CineMontage recently spoke with Ottosson about the sound in Detroit while he was sitting behind his ProTools S6 sound mix console in the Burt Lancaster Theatre at Sony Studios in Culver City. “With Kathryn’s movies, people fall into the movie,” he says.

A good deal of credit for that should go to Ottosson. Even with closed eyes, the clarity and fullness of the sounds themselves keep the images visible in viewers’ minds. Two Oscars for Best Sound Editing — for Bigelow’s Zero Dark Thirty (2012) and The Hurt Locker — and another for Best Sound Mixing (shared with production sound mixer Ray Beckett, CAS) on The Hurt Locker — are a testament to these skills.

AP Photo/Jennifer Graylock.

Although Detroit started shooting late in July, 2016, Bigelow had told Ottosson six months earlier to be available for the upcoming project. He did not start working full time on the show until February 2017 — three months after post had started — but he had already started pulling sounds from his library back in August, shortly after production began.

Over the second half of 2016, Ottosson also worked as re-recording mixer on the Netflix Lemony Snicket TV series, A Series of Unfortunate Events (2017), and as sound supervisor/sound designer/re-recording mixer on DreamWorks Animation’s feature The Boss Baby (2017). As Detroit approached wrapping, however, he came in for two stressful days in October to create a temp mix of sound elements to play with the 8-reel first cut that picture editors William Goldenberg, ACE, (who also worked on Zero Dark Thirty) and Harry Yoon had done so far.

Courtesy of DreamWorks Animation.

Dialogue editor Robert Troy (who also worked on The Hurt Locker) came on full time at the end of October when shooting ended. As in Locker, there was only a miniscule amount of ADR done for Detroit, and eight additional weeks of post were required to clean up the production dialogue for use in the film.

Ottosson explains, “In ADR, we couldn’t match the emotional pressure of the dialogue that was recorded during production, but Robert was able to tone down the source music to make the production dialogue clear. Later in post, we laid down the incidental radio music and, for the room tones in dialogue we couldn’t get rid of, I’d pre-lap the room tones for the audience to accept the wholeness.”

With virtually all of the movie’s dialogue drawn from production sound, the re-recording mixer noted the depth and range captured by production mixer Beckett. The British soundman has often worked with directors James Ivory and Ken Loach and, like Ottosson, has worked on all three of Bigelow’s most recent features.

Apart from source music that included songs of the period, there was very little original music scored for the movie. Notes Ottosson, “The sound design had to take that void of music, eliminate certain sounds and create an intimate space for the characters. Still, our intent in Detroit was to never disconnect from the reality outside and beyond the screen. Sound is almost physical in this movie; we wanted to create this awareness of the whole city.”

All the post sound work was done on the Sony lot. The sound effects editors — Hamilton Sterling, Christian Schaanning, MPSE, and Jamie Hardt, MPSE — started early in January with Ottosson joining them at the end of the month after finishing The Boss Baby. Massive amounts of Foley were created using all three Foley stages and crews at Sony, along with Foley editors Mark Pappas, Thom Brennan and Ryan Juggler, MPSE, who has been Ottosson’s assistant sound editor for about 10 years. Also coming in then were ADR and Group ADR supervisor Daniel Saxlid and ADR editor Laura Graham, MPSE.

Time in post was also needed to record and edit Group ADR or walla — the murmurs, cries, yells and screams of crowds — to give those scenes greater depth. As sound designer, Ottosson scripted crescendos of crowd sounds for 20-minute takes to convey the building of emotions into confrontation with police. To capture the outside ambience, Ottosson directed and recorded all the crowd scenes with 25 to 30 actors in Sony Studio courtyards and walkways. “For all of these actors,” he says, “there was a lot of venting from personal experience of injustice.”

As he worked from scene to scene, the sound designer sought to find sounds he could orchestrate to suggest the emotions usually evoked by an original music score. He created rhythms and counterpoints from police radios and machines that were in key scenes. In some scenes, he also subtly introduced the guttural sounds of the erhu, a Chinese two-stringed fiddle stroked with a bow. “It marries into music without being music,” Ottosson explains, “but it gives a feeling in a scene.”

Seeing no separation working as sound designer, re-recording mixer or supervising sound editor, Ottosson’s a main concern is how the sound serves the overall rhythm of the movie. “Many times during a movie, I will cut in sounds that are out of sync with what I visually cut the sound for, a door closing or a gun shot perhaps,” he explains. “What is more important to me is that the sound follow a rhythm that I feel the scene should have. I don’t want to disrupt the rhythm of the picture.”

He continues: “Sound editing is an extension of picture editing, but it works both ways. When I see the first cut, it’s clear to me what I have to do. I can hear pretty much the entire soundtrack in my head, what I want the movie to sound like.”

Ottosson would finalize the sound in scenes for himself and then work the specifics out with Bigelow and the picture editors. “Sometimes I’d turn off the picture to find the rhythm of the sounds I like, and I could suggest to Kathryn and Billy and Harry, ‘If you extend this shot for five frames, I can get this effect,’” he adds.

As for working with Bigelow, he says, “When we look at reels with Kathryn, she doesn’t give a specific note for a specific point in a scene, she talks through what she needs for the scene to work as intended. Then she trusts us to find in our own way what will address the needs of the movie. Her way of directing makes us more involved; our ownership becomes greater. I secretly think it’s a way to make us all work harder.”

The engaging animated prologue of the movie based on the paintings of Jacob Lawrence — depicting African-American migration from the rural South to urban Detroit and its industrial development — evolved during this post-production process, with writer Boal participating as well. Contributing to the effectiveness of the prologue, the sound designer revisited the musical and rhythmic sounds that emerged throughout the film to incorporate the sounds that would best underscore this historic background.

Throughout post, Ottosson would pre-dub on and off in his design room and, in May, he pre-dubbed on a large stage for four weeks to prepare for the final mix. “When we get to the mixing stage, it’s just nuances and fine tuning,” he says. “The audience shouldn’t feel we’re manipulating them in any way.”

The final mix was done over three weeks on a regular five-day-a-week schedule, with Ottosson, Bigelow, Goldenberg and supervising music editor Curt Sobel always there. Ottosson recalls, “Billy and Kathryn were super-patient with the process of preparing the sound for the pass.”

The picture was completed at the end of June after two days of print mastering, and premiered in Detroit on July 25 — 50 years to the day of the events at the Algiers Motel recreated in the film.

Born and raised in Sweden, Ottosson played keyboards in a Swedish band and came to the United States in 1987 at the age of 21 to play bass in an American band. Turning to producing music, he soon learned how to record music from other producers and engineers. Asked to produce and mix a score composed by a musician for a film, he soon became a re-recording mixer.

During the early 1990s, he cut in sound effects for audio books and worked sound for student and independent films. He gained his “on-the-job” professional training as a post sound mixer and sound effects editor for the first season of the Nickelodeon series The Secret World of Alex Mack (1994-98), which also got him into the union.

After about 10 years doing a broad range of post sound jobs in theatrical features, TV movies and documentaries, Ottosson got a boost into major big-budget features when the late producer Laura Ziskin and director Sam Raimi hired him as sound designer and supervising sound editor on Spider-Man 2 (2004). On that show, he developed a working relationship with picture editor Bob Murawski, ACE, a relationship that continued on Spider-Man 3 (2007) and The Hurt Locker the following year.

Telling now-retired DreamWorks Animation’s head of post-production Jim Beshears that he would like “to make a film that my pre-teen son could watch” led to Ottosson working on Penguins of Madagascar (2014) and, just before Detroit, The Boss Baby. With the long production schedules demanded by animated features, the company couldn’t keep sound crews on for up to three years straight. Even though Ottosson worked multiple sound jobs on these movies, he worked on the projects on and off over a year and a half while also working on live-action movies.

Comparing his two most recently released projects, Ottosson notes that animation is more “event-based with very finite things determining the pace. Each little moment requires its own precise sounds. The Boss Baby had twice as much Foley as Detroit, and the Foley schedule was twice as long.” In animation, he says, “The sound designer is a mad scientist inventing everything every time.”

For a live-action picture, especially like Detroit, he states, “The sound designer is a filmmaker and a storyteller. I have a greater responsibility to make the sound connect the different parts of the film; I have to think of the whole scene and its place in the whole movie.”

With animation, the years of preparation through script, storyboards, layouts and animation pre-determine the specific sounds required before the sound crew comes in. On The Boss Baby, the emotions attached to the various imaginary worlds of the baby’s big brother were planned in advance to be evoked by the music which runs almost non-stop throughout the movie. In this regard, Ottosson feels Detroit was very different from other live-action movies, as well. “I was not dependent on music for emotion,” he maintains.

Currently, the supervising sound editor, sound designer and re-recording mixer looks forward to working on Roland Emmerich’s big-budget World War II epic Midway, now in pre-production.