by Michael Kunkes

On July 27, that sucking sound you’ll hear at your local multiplex will be Maggie Simpson’s pacifier in all its 5.1 surround sound and widescreen glory. Maggie, along with Homer, Bart, Marge, Lisa, Mr. Burns, Smithers, Flanders and dozens of other denizens of Springfield, are making their big-screen debut. After 19 years and 400 episodes, the hit television series The Simpsons has finally spawned The Simpsons Movie, directed by David Silverman, released by 20th Century Fox and expected to be one of the biggest hits of the summer.

But it certainly won’t be one of the loudest. The Simpsons’ mindset, with its built-in, slightly fanatical audience, is that dialogue writing and all that goes with it––gag timing, topical humor, and musical and sound effects––is king. Even with a roster of A-list picture and sound editorial talent from some of the splashiest animated movies in history, as well as a Hans Zimmer score, The Simpsons Movie will not feel like most animated films of recent years, what with its 2-D production and (in comparison to most summer blockbusters) an almost minimalist soundscape.

“I started on the first day they began production dialogue, which was recorded ensemble-style with up to four characters at once on the Fox ADR stage,” says John Carnochan, a veteran animation editor whose feature work includes Robots, Beauty and the Beast, Ice Age, The Little Mermaid and The Lion King.

“This was a lot different from a typical 3-D animated show, where they go through a very long visual and story development phase,” he continues. “They already had a shooting script, cast, backgrounds and character designs, so a lot of the homework was already done. On the first day, we were already figuring out how we were going to cut it! It was almost like a radio show in that the artists are responding solely to what they hear. It was great for me because I like to start roughing out the soundtracks before I get the picture.”

The Glory of Two Dimensions

Carnochan also was thrilled to be back working in traditional 2-D animation, after years of 3-D and CGI. “You have a lot more freedom and flexibility in this process; it’s far less cumbersome and a lot easier to fix or change things,” he says. But more than anything else, he explains, “The challenge of The Simpsons Movie was about paying homage to the heritage of the series while developing a meaningful story and not being constrained by act breaks and musical play-ins and -outs.”

In a nod to the TV animation model, director Silverman did not direct the voices. “David was in charge of the visual part of the picture,” Carnochan reveals. “Executive producer James Brooks was at every recording session and very heavily involved in editing and rewriting. Producer Richard Sakai, show creator Matt Groening, Hans Zimmer and his music editor Dan Pinder were also major collaborators.”

At Fox Studios in West LA, an entirely new animation studio was assembled at what has been humorously dubbed “Stacked Animation,” in tribute to Pamela Anderson’s Stacked TV series, which was formerly housed in the complex. The facility included seven Avid Adrenaline systems, apportioned mainly to Carnochan, additional editor Mark Scheib, first assistant editor Jennifer Dolce and assistants John Currin, Vivek Sharma and Elaine Andrianos. There were also five After Effects stations.

“As we got into production, we needed to continually visualize the script––which would change after every screening––so having a quick, tight turnaround was essential,” Carnochan explains. “Our editing crew was augmented by up to 25 on-site artists, who worked in a unique way. We would listen to the dialogue and have ideas about how to stage shots. I could have a conversation with an artist about Homer’s performance and an hour or two later have a new edited version, melding picture and sound.”

Carnochan praised the 21 Wacom Cintiq systems (basically drawing tablets combined with monitors) that were installed in the studio. “You draw directly on the monitor and see your pencil strokes instantly where you draw them,” he says. “The artists export their drawings and the assistant editors import the files into the Avid for editing and further refinement if necessary. Some of the artists were specialists in either After Effects or Final Cut as well, allowing multi-planing effects.

“As a result, our story reels were very specific as to action and performance, although usually in black-and-white,” he continues. “To prepare for previews, the shots that hadn’t been animated and returned to us in color could be colored in Photoshop, and even up-rezzed to HD, which was how we previewed. The use of the Cintiqs, several terabytes of storage, Avid Unity and the file-sharing between the editorial world and visual world gave me a unique opportunity to help shape this film.”

Dolce, whose animation experience includes An Extremely Goofy Movie and Space Jam, says, “Because The Simpsons Movie is so focused on dialogue, we used script-based editing in the Avid. For over 10 years, Avid has supported a script-based program where you can load a script into a traditional Avid project and line it the way a script supervisor would line it on the set; all this does is mimic that process. She adds that although she had never used it before, it didn’t take long to realize the benefits.

Most contemporary animation directors want to emulate modern live-action films and make the sound more naturalistic.

“The writers’ assistant constantly gave us script updates in Final Draft,” Dolce continues. “John Currin was mainly responsible for lining these electronic scripts when the next round of records would come to us. Script-based editing is very quick to edit with––and it’s also a handy tool for tracking and playing back takes for the directors and writers. Takes were often reviewed in editorial as well as on the stage during any one of our four temp dubs.”

Scheib jumped at the chance to work on the movie based on his favorite television show. Primarily a single-camera comedy show editor (Arrested Development, Monk, Entourage, Crack-ing Up), Scheib says that the world of feature animation is enormously complex. “From my standpoint of working on sitcoms, what you have to work with, you work with––with the exception of re-shoots,” he explains. “In an animated feature, if a camera angle doesn’t work, a new one is quickly drawn. Or new expressions, backgrounds, shadings, etc. You don’t worry about coverage because an artist in another room will quickly pound out another version for you.”

The animation for The Simpsons Movie was completed at several studios besides Fox, including Film Roman in Burbank, Rough Draft in Glendale, and the Korean studio Akom. Each had its own sequence directors to control and divide the workload. “Working with the animators was probably my most valuable function,” adds Dolce. “I talked to them about six times a day regarding new footage and dialogue notes. We made a lot of QuickTime and AIFF files with footage-counter information so that they were aware of our new timings, and we generated a lot of written coverage via change notes on a shot-by-shot basis.”

Dolce ganged old versions with new versions and went through them manually to nail all the notes as quickly as possible in order to get them back to the studios. “There was a lot of updating all around to keep us all on the same page,” she adds. “It was not an easy task with a constantly moving target.”

The Power of the Temp Mix

The key to the sound post for The Simpsons Movie was the series of four intensive temp mixes––one every three and a half weeks. According to supervising sound editor Gwendolyn Yates Whittle, MPSE, a two-time Golden Reel Award-winner (Titanic, Saving Private Ryan), “The movie grew through each temp mix, though the main story arc has pretty much remained the same. As the temps evolved, we added a lot of things: mainly dialogue, some light ambience, sound effects––and a lot of simple, almost unnoticeable things that help fill out the track. The whole temp process was very organic and kept changing constantly as we scrambled to keep up with the picture side. It was done at breakneck speed, and the turnaround time was phenomenal––mostly because this kind of animation is so simple and easy to change.”

“Dry ice makes very odd squealing sounds when you press warm metal against it.”– Randy Thom

The temp mixes were done at Fox and Todd-AO West in Santa Monica. The staffs have varied with each mix, with the main exceptions being Whittle, temp re-recording mixer/co-sound designer Chris Scarabosio, effects editor Al Nelson, MPSE, and first assistant Stuart McCowan. “Even with all these different crews, it was the most fluid flow between dialogue and picture I’ve ever seen,” says Whittle. “On our last temp, John Carnochan was sitting next to me with his Avid laptop. I’d attach a portable hard drive, start my ProTools and away we’d go.”

Whittle adds that ProTools was an extremely flexible tool during production––even in its traditional form of use. “We’d been on so many soundstages, and so many people were working on it, that the virtual mixing thing––where everything is fluid and live and nothing gets printed––just didn’t seem to make any sense. Because of all the variables, we were carrying around every temp mix with us, and it worked out great.

“It was always an option to go back three temps and pull out that one vocal they liked,” she continues. “Most movies have a lot of layers, tons of ambience, Foley and sound design. But The Simpsons was just not that unwieldy, so we were able to use a lot of different people without having to spend days bringing them up to speed. Because it’s mainly dialogue, you just cut straight down the middle and you don’t have to do a lot of panning. It’s a much simpler show.”

“The four temp mixes have been the Rosetta Stone that we constantly refer to,” adds Nelson (winner of an MPSE Golden Reel for The Incredibles), who cut the ambiences and hard effects for the movie along with Shannon Mills and Bob Shoup. “No reel was ever locked, so we were always conforming, re-mixing and re-editing. The good part of this process was that we got multiple opportunities to fine-tune and finesse scenes as they returned to the pre-mix stage.”

McCowan, assistant supervising sound editor (whose main task was to maintain a smooth workflow at Skywalker Sound in San Rafael, California, in addition to liaising with the picture department), explains that moving the whole show down to Los Angeles for the final mix (with re-recording mixers Anna Behlmer and Andy Nelson) was a huge challenge. “Not only did we have everything on Firewire drives, but we also carried a duplicate set––and sometimes triplicate––when we were working on two stages,” he says. “It was a lot of drives to be carrying through airport security.”

The other challenge for the sound department was keeping up with the rapid pace of picture changes. “That was tricky in the best of times,” McCowan recalls. “Right before the final, we were mixing on three stages [two at Skywalker for effects and one at Fox for dialogue]. Fortunately, there are two other amazing assistants on the show––Kevin Bailey and Josh Gold––and we managed to keep everything smooth for the editors.”

Skywalker’s Randy Thom came on board as co-sound designer to create the initial sound design for The Simpsons Movie. Thom, who has won Oscars for Sound Mixing (The Right Stuff) and Sound Editing (The Incredibles), worked on the film off and on since it was in storyboard stage. He takes no issue with the show’s reliance on dialogue: “On the one hand, we walk a fine line between wanting to make it extremely cinematic and take advantage of all the things you can’t do on TV; on the other, we don’t want to turn it into a sound effects extravaganza–– which it is not––and distract the audience from what’s funny about it.

The Funny Thing About Animation

“There’s a funny thing about animation,” Thom continues, putting the movie into an historical perspective. “Everyone admires the sound created by Jimmy MacDonald and others on the classic ‘toons of the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s. But no contemporary directors or producers really want to emulate that style today in any way––and that’s at least partly because people associate that style with a short-form medium. If you attempt to do that style over the course of a feature, it gets tiring or overly ‘cartoony.’ What it comes down to is that most contemporary animation directors want to emulate modern live-action films and make the sound more naturalistic.”

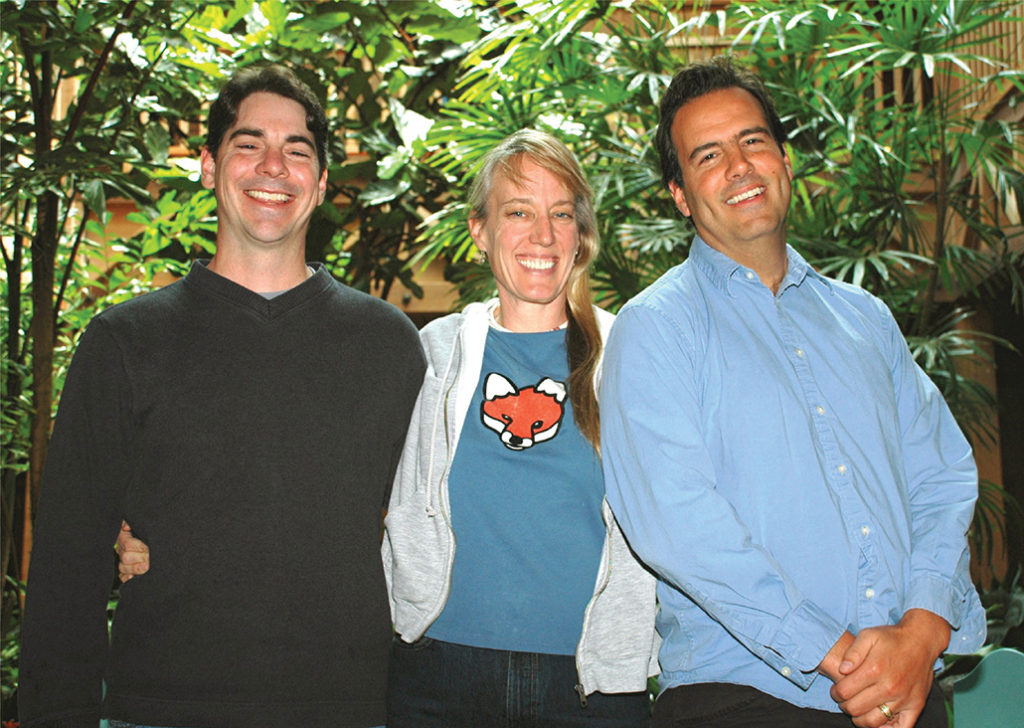

Photo courtesy of Skywalker Sound

According to Thom, the bulk of the sound effects created for The Simpsons Movie came from the Skywalker library and were then mixed with newly fabricated organic effects. In a typical Simpsons moment (without revealing any plot points) in the film, a metal silo falls into a lake so polluted that it dissolves into nothing. It was a scene that provided a bit of a sound effects challenge for Thom. Sounds of water splashing and boiling, along with the sounds of frying sausages were recorded; then dry ice was employed. “Dry ice makes very odd squealing sounds when you press warm metal against it,” explains Thom. “And it does this process called sublimation–– where the vapor just shoots off and causes the metal to resonate and sound like guitar feedback. We mixed that in with the other sounds in that scene.”

In another sequence involving a giant dome that is cracking and breaking, Scarabosio tried to get certain sounds out of splintering glass. “Glass really doesn’t like to splinter; it likes to shatter and break,” says Scarabosio, a jack-of-all-sounds whose credits include sound effects editor and re-recording mixer on Munich; sound design editor on Pearl Harbor and re-recording mixer on Star Wars: Episode III. “We recorded everything at 192 kHz and then pitched it down, but it still takes time to go through and find the best elements of the cracking and scraping, and then layer the sounds to try different effect processing. Actually, we solved the one sound design problem with one of my wife’s domed cake plates and an empty tennis ball container that I threw in there. There are lots of benefits to having a wife who knows how to bake.”

Much like old-style live action, each sound editor was assigned certain reels, as opposed to working on the movie as a whole. “As it developed, it was necessary to do things almost scene to scene,” reveals Scarabosio. “Breaking the film up into reels allowed us to develop certain scenes that were a little more solid, where other scenes were still in flux. By working in chunks, we didn’t have to be constantly conforming.”

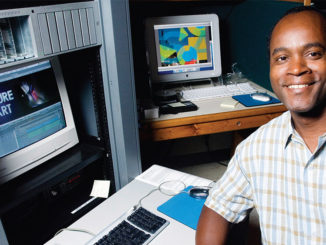

Photo by Deverill Weekes

Ideally, it would have been great to have the recording done all in one session. But the reality is that Skywalker works on a fiber channel system, so only one person can have a volume in write mode at a time. “If all the editors had the entire film in one session––and each was writing to his own volume––it would get pretty confusing as to who had done what, and who had the most updated version of a scene,” Scarabosio explains.

When it comes to sound effects, things really haven’t changed much in decades, according to Thom. “It’s still about finding and recording natural sounds in the real world and then manipulating and modifying them to do what you need them to do,” he says. Will there be a time when recording sounds won’t be necessary? “Theoretically, it’s possible to create every sound in a film electronically, including the voices,” he says. “The problem is that it’s massively inefficient and extremely expensive––so I don’t see it happening any time in the near future.”

Scarabosio says that The Simpsons Movie was not about layering sounds like in a big action film; there was far more subtlety. “It was about finding the right sounds for the right moment,” he says. “The creators and producers of The Simpsons have different aesthetics. Some have a more realistic approach; others want to see and hear more cartoonish things. It varies according to the situation and the animation as to what works best. The moment can be exciting, dangerous, tender or funny. They come and go by very fast, but each one is important.”

“Dialogue is the queen of this whole show,” explains Whittle. “The biggest challenge for all of us was to grow out of that TV sound and picture and to help support the music and dialogue with effects that fit the style and tradition that’s been set for almost 20 years––only translating it to the big screen.

“It’s all very realistic,” she concludes. “That is, if you believe in a yellow world.”