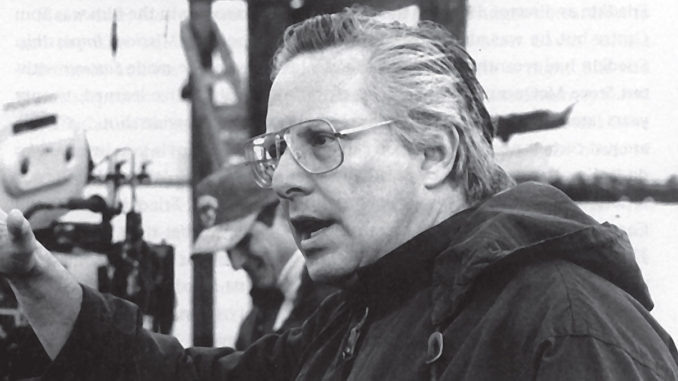

by Michael Amundsen

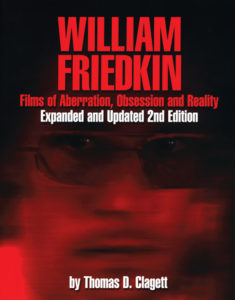

Assistant editor Thomas D. Clagett was motivated to write William Friedkin: Films of Aberration, Obsession and Reality while struggling through an especially boring stint of employment. His book has recently received a second and updated printing from Silman-James Press, a respected publisher of distinguished books on cinema and filmmaking.

When Easy Riders, Raging Bulls hit the bookshelves, it seemed to presage a wave of nostalgia for ’70s cinema. Peter Biskind’s raucous celebration of the sex, drugs and politics of ’70s American movie making was not only an entertaining read, but it left readers nostalgic for a time when big Hollywood studios actually produced independently minded movies that challenged how we in America viewed ourselves and our country. Endings were not always happy. Box office was not always king. And “pushing the envelope” was not just an excuse to show more blood and breasts.

At least, that’s how we remember it. But some wonderful movies were made in that decade. A large number of them came from the same handful of young directors, longhaired mavericks who forced the stodgy studios to conform to their desires instead of vice versa. It was an Americanized director worship, a natural extension of the auteur theory made popular by Andrew Sarris and the French New Wave. Director William Friedkin, by virtue of The Exorcist and The French Connection, was one of that pantheon of directors.

But, like so many of his contemporary peers, Friedkin hit the top running, only to stumble and collapse under the weight of his own ego and his failure to repeat those first few successes. While Easy Riders, Raging Bulls does a terrific job sharing the gossip of his sexual conquests and his set-clearing fury, Clagett has a loftier goal in mind. He wrote a serious study of each of Friedkin’s films while placing them in context consistent with his career. He makes the argument that while Friedkin’s later films failed to rise to the level of The Exorcist or French Connection, Friedkin as a stylist and as an independent voice manages to bring some element worthy of note to almost every project. Clagett is determined to inform us of what those elements are.

In chronological order, Clagett dissects each and every Friedkin feature (documentary and narrative) from The People Versus Paul Crump to Rules Of Engagement and the latest recut of The Exorcist. Drawing from first-hand interviews and contemporary news articles, he starts each chapter with the history of each film, how Friedkin became involved and the bumps along the development road. He covers both development and production, spicing both tales with first person accountings of every obstacle Friedkin had to overcome, from studio interference to casting the script.

Then, Clagett documents each film’s success at the box office, which unfortunately after The Exorcist tends to be unanimous in its sad disappointment. On its heels, Clagett critiques the artistic highs and lows of the opus in question, adding insight into what went right and far too often what went wrong.

Though lacking in the more sensational aspects of Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, William Friedkin is sharp and to the point. Clagett has given himself a lot of territory to cover and with an admirable focus accomplishes what he sets out to do. Rarely did I feel dissatisfied or cheated (though I was hoping for a more detailed account of when masked men tied up the editing crew during the production of the The Brinks Job and hijacked a load of work print, holding it for ransom). Clagett writes with a sharp, entertaining facility that he probably didn’t learn logging dailies.

But, his post-production background, I believe, is what sets this study apart. It is common for critical studies to focus on production interviews with cameramen and the set designer, while never thinking to interview the editor.

Commonly, writers treat the editing as if the director cut the film in camera and the editor was just the hands connecting already predetermined out points to clearly labeled in points. It is because of Clagett’s own background that so much credence is given to the contributions of prominent Guild Members like Ralph Rosenblum, Jerry Greenberg, and Bud Smith, whose relationship with Friedkin spanned several films. Interviews with Smith add frequent insight into not only the editing process, but the overall production as well. Again it’s Clagett’s background that places each crew interview in a collaborative context, instead of a less realistic witness of “a genius at work.”

Friedkin is not known for the warmth of his humanity or his social skills on the set. When his films were enormously successful, his abusive personality was excused as what a perfectionist had to do to get the job done. No one questions success. But, as his star faded and his artistic success dwindled, his behavior became less excusable and mostly inappropriate. Many of Friedkin’s former collaborators refused to be interviewed for this book, citing an unwillingness to be connected in any way to Friedkin’s life.

Fortunately for us, there were a large number of past associates who chose to contribute. Cinematographer Bill Butler was Friedkin’s cameraman back in his early days shooting documentaries for local television in Chicago. The opening chapter on Butler and Friedkin’s guerilla filmmaking, overcoming the lack of any kind of budget to make The People Versus Paul Crump, gives insight into the hard-nosed determination of the future director of French Connection. The documentary was so effective that its subject, Paul Crump, was removed from death row.

Friedkin contributed to the book, instructing writer Clagett that “unless it’s honest, it’s just a waste of my time.” It is to his credit that much of his participation follows his own admonition. There is little self-promotion in what he says of rewriting of his own legend. He speaks as someone still not happy with what he has accomplished, still determined to, as he puts it, “make a movie as good as Citizen Kane. ”

The newest version of The Exorcist, released a couple years back to theaters and DVD, is a good place to end the book. Frankly, after the chapter entitled Sorcerer, there is little to get excited about. Still, even missteps can be instructive. How Cruising came about is instructive on the misreading of casting, subject matter and audience. But, the chapter entitled Deal of the Century leaves even less to get excited about. After all, it is much more fun to read about movies that we made a priority to see rather than those that we avoided.

So, it’s good to end on William Blatty-driven additions to one of Friedkin’s best movies. But, the additions were not well received. It makes one wonder why Friedkin would give into their inclusion. And that by itself might be the key to his later failures. Clagett draws the book to a close citing from one of the more memorable quotations from Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. In it, Friedkin states, “I never set out to make a bad film. I thought, in each case, they were going to be as good or better than anything I had done.” He adds that his later films have no heart and no soul.

Tom Clagett’s William Friedkin: Films of Aberration, Obsession and Reality is a well researched and freshly written study. At one point, I relied on Clagett, since he had seen all of Friedkin’s films, to address my biggest curiosity: Are his later films really that bad or is it just timing? He told me that they weren’t all bad, just not as good as The French Connection.

For someone like William Friedkin, who holds such a high admiration for the works and career of Orson Welles, to have a reputation based largely on two earlier works, just like Welles, must be his greatest frustration.