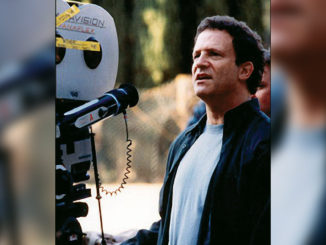

by Peter Tonguette • Stills Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

Before he became a scoring mixer, Alan Meyerson, CAS, worked in the record and advertising jingle business in New York and Los Angeles. Meyerson progressed from assistant to session engineer at studios like the Hit Factory and A&R Recording. He worked on records featuring artists like Bryan Ferry and the Commodores.

Later, he went from mixing songs to mixing film scores, but his approach to music did not entirely change. “When I work on a film,” Meyerson explains, “as I’m mixing, I’m always listening to the dialogue and the sound effects. Being an old pop music mixer, to me the dialogue is my lead vocal, so I always think of it like that.”

In a long and diverse film career, Meyerson’s methods have served him well: Working at Hans Zimmer’s Remote Control Productions — previously called Media Ventures — the scoring mixer is a frequent collaborator of the Academy Award-winning composer, working with him on such films as Gladiator (2000) and The Dark Knight (2008). Meyerson was honored with Cinema Audio Society (CAS) Awards for his work on Big Hero 6 (2014) and Dunkirk (2017).

“My job is to record the orchestra, to decide where the microphones go and to do everything that’s involved in being a recording engineer on a large-scale orchestral recording,” Meyerson explains. “I mix it all together and then deliver that to a stage as a full mix or as stems. At the dub, you want to provide the flexibility to work with the sound, so if there’s a certain element that the director doesn’t want, they can take that out.”

Yet Meyerson momentarily stopped thinking of scores like songs for one of his most personally significant projects: writer-director Terrence Malick’s World War II drama The Thin Red Line, released by 20th Century Fox in December 1998. Heading a cast featuring a host of prominent performers, Sean Penn, Jim Caviezel and Nick Nolte starred as military men who reckon with matters both practical and philosophical while in combat.

Although The Thin Red Line was drawn from a revered novel by James Jones (also the author of From Here to Eternity), and featured memorable dialogue and potent voiceover narration, little of its power sprung from words. Instead, Malick — then best-known as the long-exiled filmmaker responsible for the New Hollywood classics Badlands (1972) and Days of Heaven (1978) — made use of the searching, soaring images of cinematographer John Toll, ASC, and the haunting yet ravishing score by Zimmer. To put it another way, this was a film not in need of a “lead vocal.”

“Some of the most magical moments for me are just the visuals and the music,” comments Meyerson, who was then in his fourth year of working with Zimmer. “I kept saying to Hans, ‘This movie would work beautifully as Kabuki. This could just be visuals and music. You could tell the entire story without a single word.’”

A native of New York, Meyerson aspired to become a classical trumpet player, though his musical influences were manifold. “I was a kid who had Michael Jackson records and had Chicago Symphony Orchestra records,” he notes. “I loved all of those worlds.” He entered Brooklyn College with the goal of one day joining an orchestra but his hopes were quickly dashed. “On my first day of college, I walked around the hallways in a daze, thinking, ‘Plan A is not happening,’” recalls Meyerson, who soon spotted the setting of his Plan B: a recording studio. “I literally wandered into the recording studio of Brooklyn College,” he continues. “I met a guy named Frank Angel, and he asked me if I wanted to intern. I started interning there and went on from there.”

Yet, despite his eventual success in the music industry, Meyerson was vaguely dissatisfied. “I did an album called Technique with New Order [1989], and I did a lot of British pop music and had a couple of number one R&B hits,” he says. “But I always felt there was something I wasn’t connecting to in the pop world. I wasn’t bringing it the way I heard other people’s records bring it.”

That, combined with the emerging popularity of genres like hip-hop, persuaded Meyerson to change his medium from music to movies. His debut as a scoring mixer was on Jan de Bont’s Speed (1994), starring Sandra Bullock. “The minute I hit my first movie, I thought, ‘Wow, this is what I’m supposed to be doing,’” Meyerson comments. “It went on to win an Academy Award for Best Sound [for Mixing, as well as another Oscar for Best Sound Effects Editing], so somehow or another, I got some credibility right off the bat.” Meyerson’s association with Zimmer began on his sophomore effort, Penny Marshall’s Renaissance Man (1994).

“I met Hans on a drum recording session,” Meyerson remembers. “They called me back the next day, so I thought I had done something wrong. But I came in and he said it had been a really great session and what was I doing for the next couple of months? That was 24 and a half years ago.”

The scoring mixer says that the composer responded to his background, which blends classical music with modern recording techniques. “That sort of sound has become so popular in film now,” he explains. “It’s not a pure orchestral sound, but an orchestral sound mixed with guitars and drums. I was the right person at the right time to get involved with that; I had done records for so long, and I also understood orchestral music.”

Meyerson’s expertise — as well as his schedule — was put to the test on The Thin Red Line, for which he estimates that Zimmer composed between four and five hours of music. “At that point, I was a single guy, and there was no place in the world I’d rather be than in the studio working,” Meyerson reflects. “Hans likes to work late nights, so I literally would just sit on the couch and watch him write until 3 or 4 in the morning. It took him a while to find his voice in that film, but once he did, it was almost like magic.”

Meyerson was present at the creation when Zimmer arrived at the motif for “Journey to the Line,” which became one of the film’s most memorable passages, both mournful and stirring. “Hans’ door was open and I heard ‘Journey to the Line,’” Meyerson recalls. “I thought to myself, ‘He got it. That became one of the most iconic pieces in the film.” The cue is still deployed in trailers and chosen as temp music. “It’s sort of like Samuel Barber’s ‘Adagio for Strings,’” Meyerson notes. “It’s ended up as part of the vernacular of film music.”

Because of the volume of music composed by Zimmer, the score was recorded in fits and starts. “We did groups of sessions,” Meyerson relates. “It wasn’t all done at one time. We would record a bunch of music, we would mix it, we would deliver it — and then we would record a bunch of music, mix it and deliver it.” Zimmer preferred to record sections of the orchestra independent of each other. “We did the brass separate from the strings and the woodwinds,” says the mixer, who decided to record the cellos with a new ribbon microphone, the R-121. “I borrowed about eight of them,” he says. “It was the first time that microphone got used in an orchestral session, and now they’ve become a mainstay of orchestral recording.”

Zimmer’s fastidiousness also contributed to the length of the process. “Hans spends a tremendous amount of time at the beginning of a movie teaching the orchestra what the voice is, how to play the notes, how the blends and the balances and the dynamics are supposed to be,” Meyerson observes. “Once they get it, they got it, and you start moving really, really quickly. The Thin Red Line was one of those experiences where he really wanted a certain thing from the orchestra.”

Equally demanding was the recording of an unusual instrument referred to as the “cosmic beam,” which was performed by Francesco Lupica. “It’s like an I-beam from a building strung with piano wire,” Meyerson says. “Francesco uses this crossbar and he shakes it and he smacks it, and he has rubber hammers that he hits strings with.” Initially, the plan was to record the beam in a warehouse in the San Fernando Valley. “I went out to hear this beam with a bunch of microphones and a little 8-track digital tape recorder,” the scoring mixer recalls. “I thought, ‘There is no way I’m going to be able to capture the sound in this space.’” He played the results for Zimmer; “The sound was so loud that it totally compressed the air in the room.”

Changing course, arrangements were made for Lupica to perform the beam on a soundstage at Fox. “We set up three TEAC DA-88s, and I had 23 microphones,” Meyerson explains. “I went up into the rafters with a bunch of these B&K microphones that could handle enormously loud volumes and found spots where the sound sounded interesting to me, so I would hang the microphones down from there. I then walked around on the bottom until I found little pockets of low frequencies that sounded interesting to me and I would put a microphone there.”

Of course, the beam is heard fairly fleetingly in the finished film. “It’s when they start going up the hill for their attack,” Meyerson says. “It’s a sustained, very anxiety-ridden-sounding tone. You spend an incredible amount of time making this thing, and then they use it for 30 seconds in the movie.”

Nonetheless, the scoring mixer says that his overall experience on the film taught him much about mixing in movies. “In those days, Hans would come into the mix with me and would actually push faders,” Meyerson says. “I would get this beautiful sound, and this really, really gorgeous balance, and then he would mess it up — but in the best way possible.” Zimmer repeated seven-note phrases, in the process creating waves of sound. “I learned that I don’t have to stick to what would be considered a traditional balance,” Meyerson reflects. “I could take it to a different level.”

In the end, Zimmer and Meyerson’s work together reflected the aims of Malick, who was present during the mix. “We kept hearing him say the word ‘oceanic’ — the music had to have this oceanic feel,” Meyerson reveals. “In his mind’s eye, he wanted the musical equivalent of that visual concept.” Malick was not always in such a grandiose state of mind, however. “Whenever he was leaving, he would ‘mosey,’” Meyerson recalls. “He would say with that Southern accent, ‘I got to mosey.’”

For his part, Meyerson is happy to mosey through his memories of The Thin Red Line. “I’m so grateful for those times and the great opportunities that I had,” he says.