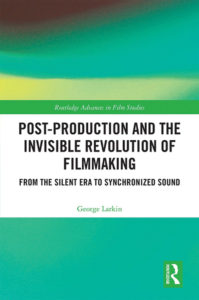

Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution of Filmmaking: From the Silent Era to Synchronized Sound

by George Larkin

Routledge

Hardcover 238 pages $140

ISBN # 978-1-138-58833-2

by Betsy A. McLane

George Larkin offers a startling premise in the book Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution of Filmmaking: From the Silent Era to Synchronized Sound, one that may delight some readers while offending others. He states the fact that post-production work is critical to all filmmaking but takes that fact further, stressing that post is the major driver of film creation, eclipsing all else.

The author acknowledges that producing, writing, designing, cinematography, acting and directing exist, but insists that true cinematic control is found in post-production. “The post-production process can thus be viewed as the master over the artistry of other film workers as all their efforts are finalized as part of that system,” he writes. This stance will likely surprise those writers, producers and directors, let alone cinematographers, who see themselves as auteurs. Post-production artists will need to judge for themselves.

Despite the long, impressive and justifiably proud history of film editing, and the reliance of some unfortunates on the belief that “We can fix it in post,” most editors are quick to give credit to those who created the sounds and pictures that arrive in the editing room. There are disagreements and blow-ups, of course, and the best producers and directors learn to trust their editors’ instincts. It is the extremely rare editor, especially a sound editor, who gets final say on the shape of any project. Editors also tend to be unseen and somewhat modest, certainly before the public, as well as to many in the business.

Despite the long, impressive and justifiably proud history of film editing, and the reliance of some unfortunates on the belief that “We can fix it in post,” most editors are quick to give credit to those who created the sounds and pictures that arrive in the editing room. There are disagreements and blow-ups, of course, and the best producers and directors learn to trust their editors’ instincts. It is the extremely rare editor, especially a sound editor, who gets final say on the shape of any project. Editors also tend to be unseen and somewhat modest, certainly before the public, as well as to many in the business.

To make his thesis viable, the author provides a detailed exploration of the US movie industry as it shifted from silent to sound films. As he states in his conclusion, “This book examines transitional periods where changes in technology and process influence craft” (italics Larkin’s). Almost all writers on film, as well as those who make the films, acknowledge this relationship, and although Larkin claims that few have examined it, there is a rapidly growing body of writing on post-production processes — particularly writing and research about sound. So here is the rub: Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution is a useful addition to movie history, if the reader can lay aside the constantly restated claim that post is the most important part of filmmaking.

Following lengthy introductions in Chapters 1 and 2, the third chapter surveys silent film-era exhibition practices, specifically the sounds and music orchestrated by exhibitors that almost always accompanied public screenings. Larkin’s research backs up his statements about the control that theatre owners and musicians had in the “final mix” of sounds heard by audiences.

An example of his extensive and admirable research is inclusion of an account by conductor Orville Mayhood entitled “Dramatic Music and the Big Picture,” and found in a 1916 issue of the Motography, an early movie industry magazine. Mayhood describes his work conducting composer Joseph Breil’s score for D.W. Griffith’s three-and-a-half hour Birth of a Nation (1915), although both he and Larkin ignore Breil’s contribution by crediting the score to Griffith. Mayhood, who apparently conducted at over 600 screenings of the opus, writes that for New York City screenings of the film, he would quiet the orchestra at the film’s end to engender applause, while for Chicago showings he would raise it to a crescendo to achieve the same reaction.

That is indeed a level of control; imagine John Williams asking that the volume be turned up or down in a theatre in response to the screening location. Larkin goes on to bring in Cecil B. De Mille, who is quoted in the same publication as stating, “Better to Have None at all than to Murder Good Pictures Killed with Trashy Music” (capitalization in original).

Independent research is a strength in Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution of Filmmaking. Larkin scoured the resources of the Pacific Film Archive, the Margaret Herrick Library of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Paramount Archives and others. Of note is the author’s acknowledgement of assistance from the Motion Picture Editors Guild and the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers (SMPTE). It is to the latter that he owes the most thanks. (SMPTE was SMPE during this period, founded in 1916 before the medium of television existed.) The Journal of the of the Society of Motion Pictures Engineers and the Transactions of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers are the most often cited sources among the book’s plethora of footnoted publications.

Within SMPTE’s long history as the arbiter of all things technical in the moving image industries, the recommendation of standards during the shift from silent to sound films remains key among its achievements. The author draws on a variety of facts and opinions discussed by SMPE authors. Larkin, among other film historians, finds that SMPE publications “reveal that for early film technicians, there was a growing sense of aesthetic considerations for artistic purposes in their engineering work, all based upon the medium as a living one, a biological entity.” In defense of this argument, he offers a 1924 diagram conceived by then-SMPE president L.A. Jones, which he captions as “The motion picture organism.” Whether to accept the conclusion that SMPE members believed that film was a “living medium” is best left to the reader.

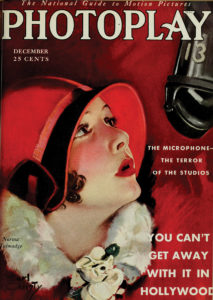

In contrast to the specialized content from SMPE, Larkin also utilizes the period’s popular fanzines. These references are most effective in revealing how synchronous sound changed the public’s relationship to movies — especially the often-discussed question of which stars would suffer ruined careers when audiences heard their voices. Here, Hollywood’s publicity machine is shown reproducing the crisis, characterized by a 1929 Photoplay cover featuring a close-up of Norma Talmadge (although Larkin fails to identify the star) gazing hopefully up through long lashes at a microphone. Tag lines on the cover proclaim: “The Microphone – The Terror of the Studios” and “You Can’t Get Away with It in Hollywood.”

In contrast to the specialized content from SMPE, Larkin also utilizes the period’s popular fanzines. These references are most effective in revealing how synchronous sound changed the public’s relationship to movies — especially the often-discussed question of which stars would suffer ruined careers when audiences heard their voices. Here, Hollywood’s publicity machine is shown reproducing the crisis, characterized by a 1929 Photoplay cover featuring a close-up of Norma Talmadge (although Larkin fails to identify the star) gazing hopefully up through long lashes at a microphone. Tag lines on the cover proclaim: “The Microphone – The Terror of the Studios” and “You Can’t Get Away with It in Hollywood.”

In Chapter Four, “Transition to Post-Production: The Rise and Fall of the Monitor Man,” the author provides the most entertaining stories; those about the dreaded and feared “Monitor Man” (italics mine). This was the term, common for only a few years, used to refer to a sound recordist/mixer working onstage during production. Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution positions the Monitor Man at the fulcrum of the complicated switch to synchronized sound.

Usually lodged high above the stage in a sound booth, this technician was hyperbolized in 1930 by Photoplay: “They call him God around the studio and god indeed he is, since he controls the destinies of the famous ones of filmdom… He is the Jove of Hollywood, the Wotan of the screen world. He sits high above the stars and looks down on them.” The Monitor Man was in effect also the sound editor, particularly within the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. What sound editor today would not wish to be thought of as cinema’s Wotan, a god of pre-Christian Germanic tribes?

Discs and other very early sound recording devices did not lend themselves to post-production editing, so recording and mixing took place using a variety of techniques. Larkin quotes Carroll Dunning (vice president of the Prizma Color Process Company, although not identified by Larkin as a key player in early color and process photography) from an SMPE publication in 1929 describing how multiple sound sources were recorded simultaneously while cameras rolled for a nautical scene:

“The sound of the side-wash of the water was picked up by hanging a microphone over a water-filled box through which a workman swished a wooden paddle. A second mike [sic] picked up the dialogue and song while a third recorded the orchestral accompaniment of a Hawaiian orchestra, supposedly midships of our nailed-to-the floor yacht.” All of this occurred at the same time on different parts of the same stage. Other accounts in this chapter are similarly intriguing.

Such tidbits of Hollywood history are fascinating and worth gathering in a book — and Larkin recounts them well. He goes on to discuss topics like the increased need for continuity in filming and post-production practices as these became codified. Still, the lovely examples, such as a photograph positioned near the book’s end of an attractive female caressing a 1928 Moviola, fail to support Larkin’s thesis, rephrased repeatedly, that true authorship of a film is found in post-production.

Better to present the many facts and fascinating stories imbedded in Post-Production and the Invisible Revolution as a straightforward history, unburdened by an overlay of academic theory.